Three-factor theory of personality by G. Eysenck. Theories of personality. Factors promoting development in Eysenck's theory

Hans Eysenck's theory of personality types

The English scientist Hans Eysenck (1916-1997) entered the history of psychology as the creator four-level hierarchical model of human personality. Like Cattell, Eysenck used mathematical tools for his theory factor analysis, however, his approach differed from Cattell's. Firstly, he used the hypothetico-deductive method of processing the material before using factor analysis. Secondly, the scientist considered factor analysis to be only one of the ways to find answers to the most important questions regarding personality theory. Thirdly, he identified NOT traits, but only three bipolar superfactors: extraversion - introversion, neuroticism - stability, psychoticism - ego. Extraver sat down characterized by sociability and impulsiveness; introversion - passivity and thoughtfulness; neurotizle - anxiety and habits; stability - lack of them; penchotism - antisocial behavior; and the ego - a tendency towards empathy and cooperation.

Eysenck was deeply convinced that personality traits and types are determined primarily by heredity. According to his theory, environmental influences are practically unimportant for the formation of personality. In his opinion, genetic factors have a much greater influence on future behavior than childhood impressions.

Eysenck formulated the concept of a hierarchical four-level model of human personality. Lower level - specific actions or thoughts, an individual way of behaving or thinking that may or may not be characteristics of the individual. The second level is habitual actions or thoughts that are repeated under certain conditions. Third level - personality traits, and the fourth, highest level of organization of behavior is the level of types, or superfactor.

Eysenck conducted a detailed empirical study of the psychological characteristics of extroverts and introverts, and in the light of his data, their psychological portraits can be described.

Extroverts They are open, friendly, and easily establish contacts with people who have many acquaintances and friends. Extroverts constantly strive for new vivid impressions and sensations, usually show carelessness and are easily distracted from life's problems. Extroverts are active, decisive, speak and act quickly, without thinking. Extroverts love change and are happy-go-lucky and optimistic. It is common for them to act rather than indulge in reflection; they show intemperance and can behave aggressively.

Introverts They avoid too strong impressions, control their feelings, and strive for a calm, orderly life. They strive for situations that they know well and avoid too sudden changes or surprises. Introverts love work that requires long-term attention and concentration from them, and it is not easy for them to be distracted from their activities and activities. They think for a long time before doing or saying something. They move slowly, their movements are slow. Be careful, they don't like taking risks.

Eysenck put a lot of effort into finding out what significant differences in behavior are determined by the extraversion-introversion parameter. The scientist identified the following differences between extroverts and introverts:

1. Extroverts achieve a level of optimal functioning in stimulating situations. Introverts achieve a level of optimal functioning in the absence of strong stimulation

2. Introverts are more likely to succeed in learning.

3. Extroverts feel more alert in the evening, and introverts feel more alert. Extroverts work better in the afternoon, while introverts work better in the first half.

4. Introverts are more patient with pain than extroverts, they get tired faster, and excitement interferes with their activities. Introverts are more focused on accuracy at work, rather than speed, unlike extroverts.

5. Extroverts are more active in the sphere of sexual relations, begin sexual activity at an earlier age, have more partners and change them more often.

6. Extroverts tend to break traffic rules, therefore they are more likely to be involved in accidents than introverts.

7. Extroverts are less frugal and tend to spend money lavishly.

8. Extroverts are prone to those types of activities that involve: people (trade, social services). Introverts prefer theoretical and scientific activities (engineering, chemistry).

9. Extroverts perform better in the beginning, and then their performance decreases. Introverts are initially less effective than extroverts, but subsequently their performance increases.

10. The activity of extroverts is quickened if they expect reward, and introverts - if they are threatened with punishment.

The practical value of the results obtained lies in the fact that the influence of the nature of stimulation on the activities of different people becomes clear. It will not be possible to motivate an extrovert by threatening punishment (dismissal, deprivation of bonuses), and for an introvert encouragement and rewards are not of much importance.

The most important conclusion that Eysenck’s research on the parameters of extraversion and introversion led to can be briefly presented as follows: extraversion-introversion is an important dimension of personality and determines many options for its social behavior.

Rashond Cattell's structural theory of personality traits

Raymond Cattell (1905-1998) is one of the most influential and original psychologists working in the fields of individual differences, intelligence and personality, psychometrics and behavioral genetics.

Cattell considered the goal of psychological research of personality to be to establish the laws by which people behave in all types of social situations and in typical environmental situations. Raymond Cattell devoted a significant part of his life to creating a complete diagram of certain properties of the human personality. It was he who first identified an almost exhaustive list of normal and abnormal temperamental and structural traits. Cattell then moved on to measure personality dynamics, finding traits he called motivational. According to Cattell, knowing the structure and dynamics of personality, one can successfully predict the behavior of a particular person.

Over many years of work, Cattell created an original theory of personality based on psychometric research. Using an inductive method, he collected quantitative data from three sources: data on actual behavior throughout life, people's self-reports and the results of objective tests, calculated cross-correlations of values and formed correlation matrices. The scientist identified the main structures (primary factors) that determine personality. In total, the psychologist identified 35 first-order personality traits, of which 23 traits are characteristic of a normal personality and 12 indicate pathology. As a result of repeated factor analysis, Cattell was able to identify eight second-order rices. Primary and secondary factors in Cattell's theory are called "basic personality traits", and, accordingly, the theory itself is called trait theories

Cattell became so keen on studying traits that he discovered a desire to use them to describe not only the personality of an individual person, but also the social groups in which he belongs. Cattell noted that personality is influenced by both situational factors and the groups to which it belongs. He proposed a special term to designate a range of rices that can be used to describe a particular group - synthality.

Cattell found that, compared to British students, American students were more extroverted, radical and had a stronger superego, while British students were more conservatist and had a stronger ego strength. Cattell also concluded that Americans are less emotional than other nations. It can be said that such a fantastic attempt, using empirical methods, to describe in detail the features characterizing society as a whole, was carried out by a single psychologist, Cattell, which testifies to his extraordinary scientific courage.

After almost sixty years of work, Cattell, who set himself the task of creating a complete map of personality, succeeded in creating a comprehensive qualification of personality structures, and also developed a method for predicting personality behavior. Cattell's theory is undoubtedly the most comprehensive system of views on personality in modern psychology, based entirely on the use of precise empirical research methods.

Eysenck Hans Jurgen (born March 4, 1916) is an English psychologist, one of the leaders of the biological direction in psychology, the creator of the factor theory of personality. Educated at the University of London (Doctor of Philosophy and Sociology). From 1939 to 1945 he worked as an experimental psychologist at the Mill Hill Emergency Hospital, from 1946 to 1955 he was the head of the Department of Psychology at the Institute of Psychiatry at Maudsley and Bethlem Hospitals, which he founded, from 1955 to 1983. . - Professor at the Institute of Psychology at the University of London, and from 1983 to the present - Emeritus Professor of Psychology.

Founder and editor of the journals Personality and Individual Differences and Behavior Research and Therapy. He began his research on basic personality traits with an analysis of the results of a psychiatric examination, including descriptions of psychiatric symptoms, of a contingent of soldiers - groups of healthy people and those recognized as neurotic. As a result of this analysis, 39 variables were identified in which these groups turned out to be significantly different and factor analysis of which made it possible to obtain four factors, including the factors of extraversion-introversion and neuroticism ("Dimensions of Personality", L. 1947). As a methodological basis, Eysenck focused on understanding the psychodynamic properties of personality as determined genetically and ultimately determined by biochemical processes ("The Scientific Study of Personality", L., 1952). Initially, he interpreted extraversion-introversion on the basis of the relationship between the processes of excitation and inhibition: extroverts are characterized by the slow formation of excitation, its weakness and the rapid formation of reactive inhibition, its strength and stability, while introverts are characterized by the rapid formation of excitation, its strength (this is due to better education they have conditioned reflexes and their training) and the slow formation of reactive inhibition, weakness and low stability. As for neuroticism, Eysenck believed that neurotic symptoms are conditioned reflexes, and behavior that is the avoidance of a conditioned reflex stimulus (danger signal) and thereby eliminating anxiety is valuable in itself.

In his work “The Biological Basis of Personality”, Spriengfield, 1967, Eysenck proposed the following interpretation of these two personality factors: a high degree of introversion corresponds to a lower threshold for activation of the reticular formation, therefore introverts experience higher arousal in response to exteroceptive irritants, and a high degree of neuroticism corresponds to a decrease in the activation threshold of the limbic system, so they have increased emotional reactivity in response to events in the internal environment of the body, in particular, to fluctuations in needs. As a result of further research using factor analysis, Eysenck came to the formulation of the “three-factor theory of personality.”

This theory is based on the definition of a personality trait as a way of behavior in certain areas of life: at the lowest level of analysis, isolated acts in specific situations are considered (for example, the currently manifested manner of entering into a conversation with a stranger); at the second level - frequently repeated, habitual behavior in essentially similar life situations, these are ordinary reactions diagnosed as superficial traits; at the third level of analysis, it is discovered that repeated forms of behavior can be combined into some uniquely defined complexes, first-order factors (the habit of being in company, the tendency to actively engage in conversation, etc. give grounds to postulate the presence of such a trait as sociability); finally, at the fourth level of analysis, meaningfully defined complexes themselves are combined into second-order factors, or types that do not have an obvious behavioral expression (sociability correlates with physical activity, responsiveness, plasticity, etc.), but are based on biological characteristics. At the level of second-order factors, Eysenck identified three personality dimensions: psychoticism (P), extraversion (E) and neuroticism (N), which he considers as genetically determined by the activity of the central nervous system, which indicates their status as temperamental traits.

In the vast number of applied studies that Eysenck carried out to prove his theory, most often together with specialists in the relevant fields, the importance of differences in these factors was shown in crime statistics, in mental illness, in susceptibility to accidents, in the choice of professions, in the severity of level of achievements, in sports, in sexual behavior, etc. Thus, in particular, it has been shown that according to the factors of extraversion and neuroticism, two types of neurotic disorders are well differentiated: hysterical neurosis, which is observed in persons of choleric temperament (unstable extroverts) and obsessive-compulsive neurosis - in persons of melancholic temperament (unstable introverts). He also conducted numerous factor-analytic studies of various psychological processes - memory, intelligence, social attitudes.

Based on the “three-factor model of personality,” he created the psychodiagnostic methods EPI (“Manual of the Eysenck Personality Inventory” (jointly with Eysenck B.G.), L., 1964) and EPQ, which continued a number of previously created ones - MMQ, MPI (“Manual of the Maudsley Personality Inventory”, L., 1959).

Eysenck is one of the authors of the “three-phase theory of the emergence of neurosis” - a conceptual model that describes the development of neurosis as a system of learned behavioral reactions (“The Causes and Cures of Neuroses” (with Rachmann S.), L., 1965); Based on this behavioral model, methods of psychotherapeutic personality correction were developed, in particular one of the variations of aversive psychotherapy and neurosis, constitution and personality.

Cattell lists at least 16 traits or factors that make up personality structure. And finally, Eysenck attaches much greater importance to genetic factors in the development of an individual. This does not mean that Eysenck denies situational influences or the influence of the environment on a person, but he is convinced that personality traits and types are determined primarily by heredity.

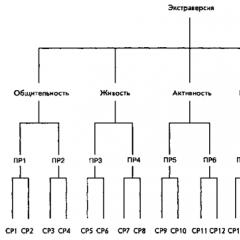

Rice. Hierarchical model of personality structure. PR - habitual reaction; SR - specific reaction.

The dispositional direction assumes that people have certain stable internal qualities that persist over time and in different situations. In addition, it is emphasized that individuals differ from each other in their characterological characteristics. Gordon Allport, who first put forward the theory of personality traits, considered the main task of psychology to be the explanation of the uniqueness of the individual. He viewed personality as a dynamic organization of those internal mental processes that determine its characteristic behavior and thinking.

Allport considered the trait to be the most significant unit of analysis for understanding and studying personality. In his system, a personality trait is defined as the predisposition to respond in a similar way to different types of stimuli. In short, personality traits explain the persistence of a person's behavior over time and across situations. They can be classified as cardinal, central and secondary depending on the breadth of their spectrum of influence. Allport also distinguished between general and individual tendencies. The former are common traits by which most people within a given culture can be compared, while the latter refer to characteristics specific to a person and cannot be used as a criterion for comparing people.

A comprehensive construct that unites personality traits and gives direction to a person’s life is called proprium. This concept stands for "Self as Knowable" and includes all aspects of the individual involved in creating an internal sense of wholeness. Another key point in Allport's theory is the concept of functional autonomy. It states that the motives of an adult are not related to the past experiences from which they originally arose. Allport distinguishes stable functional autonomy (feedback mechanisms in the nervous system) and functional autonomy proper (acquired interests, evaluations, attitudes and intentions). The latter contributes to the development of a truly mature personality, the characteristic features of which Allport described in great detail.

Allport's opposition to psychoanalytic and behaviorist concepts of personality is clearly visible in his basic assumptions about human nature. His theory of personality traits reflects:

Strong commitment to the basic principles of rationality, proactivity and heterostasis;

Moderate commitment to holism and knowability;

Weak preference for freedom and subjectivity;

The average position on the provisions of constitutionalism-environmentalism and changeability-immutability.

Although personality trait theory has to date stimulated almost no empirical research directly supporting its core concepts, Allport has made some interesting empirical contributions to the personality literature. He advocated an ideographic approach to the study of personality, aimed at revealing the uniqueness of each person. One such study (Jenny's Letters) was cited to illustrate the potential value of personal documents in identifying the unique set of traits characteristic of a given individual.

Personality trait theories have come under criticism in recent years. Michel argues that people at different times in different situations show less constancy than is declared by psychologists - supporters of the concept of traits. He insists that behavior is determined primarily by situational factors. Proponents of the trait concept have put forward a counterargument: consistency can be proven, but to do this it is necessary to adequately measure observed behavior. According to Epstein, when behavior is measured across a range of occasions, then we become confident that personality traits predict consistent behavioral tendencies. Some personologists argue that significant correlations between personality traits and behavior can only be obtained in cases where the subjects have a pronounced trait. A study based on self-report measures of friendliness and conscientiousness was cited to support this view. Finally, it has been noted that the interaction between personality traits and situational factors is becoming the dominant view in personology.

The applied significance of Allport's theory in connection with the "Study of Values" test is considered. Based on Spranger's value types, this personality self-esteem questionnaire measures the comparative salience of six different value orientations that Allport considered essential in a unifying philosophy of life. Brief descriptions of the types of people whose lives are determined by the predominant influence of theoretical, economic, aesthetic, social, political or religious values were presented.

Factor analytic theorists Raymond Cattell and Hans Eysenck used a complex statistical procedure to identify the traits underlying personality structure. Factor analysis is a tool for determining the degree of covariation among a large number of variables measured in a large number of people. This procedure was described as a sequential series of steps: collecting measures of variables from a large sample, creating tables of interactions between the measured variables (correlation matrices), determining the loadings on each factor, and assigning names to the resulting factors.

Cattell views personality as that which allows us to predict the actions of a person in a given situation and is expressed by the equation R = f (S, P). According to Cattell, personality traits are hypothetical constructs that predispose a person to engage in consistent behavior over time and under different circumstances. He describes the personality structure as consisting of approximately 16 factors - initial traits. In turn, the initial features can be divided into constitutional and environmentally shaped. Skill or ability, temperament, and dynamic traits are additional categories of personality trait qualifications in Cattell's system. Cattell also distinguishes between common and unique features.

To identify baseline traits, Cattell uses three types of data: vital records (L-data), self-report questionnaires (Q-data), and objective tests (OT-data). The Sixteen Personality Factors (16 PF) questionnaire was developed by Cattell to measure baseline self-reported personality traits. Cattell also developed a kind of statistical manual called multilateral abstract variant analysis for estimating the relative contribution of heredity and environment to the formation of a given trait. He believes that personality is determined one-third by genetics and two-thirds by environmental influences. Finally, he examined how synthality, or the defining characteristics of groups, influence the individual.

Eysenck's theory of personality types is also based on factor analysis. His hierarchical model of personality structure includes personality types, personality traits, habitual responses, and specific responses. Types are continuums on which the characteristics of individuals are located between two extremes. Eysenck emphasizes that personality types are not discrete and that most people do not fall into extreme categories.

Unlike Cattell, Eysenck sees only two main types (supertraits) underlying the personality structure: introversion-extraversion and stability-neuroticism. The obvious behavioral features that result from combinations of these two types are considered. For example, people who are both introverted and stable tend to be in control of their actions, while extroverts who are stable tend to act carefree. Eysenck argues that individual differences in these two supertraits, as well as a third factor called psychoticism - superego strength, are closely related to the neurophysiological characteristics of the human body. Eysenck attaches much more importance to the genetic basis of personality traits than does Cattell.

Eysenck developed several questionnaires to assess the three main supertraits that underlie his hierarchical model of personality. The Eysenck Personality Questionnaire was described, as well as a study conducted using it, demonstrating the difference in behavior between introverts and extroverts.

Cattell Questionnaire

The Cattell Questionnaire is one of the most common questionnaire methods for assessing individual psychological characteristics of a person both abroad and in our country. It was developed under the guidance of R.B. Cattell and is intended for writing a wide range of individual-personal relationships.

A distinctive feature of this questionnaire is its focus on identifying relatively independent 16 factors (scales, primary traits) of personality. This quality was identified using factor analysis from the largest number of superficial personality traits originally identified by Cattell. Each factor forms several surface features, united around one central feature.

The Cattell questionnaire includes all types of tests - assessment, test decision, and attitude to any phenomenon.

Before the survey begins, the subject is given a special form on which he must make certain notes as he reads it. The corresponding instructions are given in advance, containing information about what the subject should do. Control test time is 25-30 minutes. In the process of answering questions, the experimenter controls the time the subject works and, if the subject answers slowly, warns him about this. The test is carried out individually in a calm, business-like environment.

The proposed questionnaire consists of 105 questions (form C), each of which offers three answer options (a, b, c). The subject selects and records it on the answer form. During the work, the subject must adhere to the following rules: do not waste time thinking, but give the answer that comes to mind; do not give vague answers; don't skip questions; be sincere.

Questions are grouped according to content around certain features that ultimately lead to certain factors.

For results to be reliable, they must be confirmed using other techniques or using another form of the same test.

The results of applying this technique make it possible to determine the psychological uniqueness of the main substructures of temperament and character. Moreover, each factor contains not only a qualitative and quantitative assessment of the internal nature of a person, but also includes its characteristics from the perspective of interpersonal relationships. In addition, individual factors can be combined into blocks in three areas:

- Intelligent block: factors: IN- general level of intelligence; M- level of development of imagination; Q1- receptivity to new radicalism.

- Emotional-volitional block: factors: WITH- emotional stability; ABOUT- degree of anxiety; Q3- presence of internal stresses; Q4- level of development of self-control; G- degree of social normalization and organization.

- Communication block: factors: A- openness, closedness; N- courage; L- attitude towards people; E- degree of dominance - subordination; Q2- dependence on the group; N- dynamism.

To some extent, these factors correspond to the factors of extraversion-introversion and neutroticism according to Eysenck, and can also be interpreted from the point of view of the general orientation of the personality: towards the task, towards oneself, towards others. In this regard, this technique can be used in combination with the study of temperamental personality traits according to Eysenck (57 questions) and the Smekal and Kucher technique, adapted by Peysakhov, to identify the general orientation of the personality.

Stimulus material (list of questions)

1. I think my memory is better now than before:

c) It's hard to say

2. I could live happily alone, far from people, like a hermit:

c) Sometimes

3. If I said that the sky “is below” and that it is “hot” in winter, I would have to name the culprit.

a) Gangster

c) Saints

4. When I go to bed, I:

a) I fall asleep instantly

c) something in between

c) I fall asleep slowly, with difficulty

5. If I were driving a car on a road with many other cars, I would feel satisfied:

a) If I stayed behind other cars

b) I don't know

c) If I overtook all the cars ahead

6. In company, I let others joke and tell all sorts of stories:

c) Sometimes

7. It is important to me that there is no clutter in everything that surrounds me.

c) it's hard to say

c) incorrect

8. Most of the people I meet at the party are happy to see me.

c) Sometimes

9. I would rather do:

a) Fencing and dancing

c) It’s hard to say

c) Wrestling and hand ball.

10. I laugh to myself that there is such a big difference between what people do and what they say about it.

c) Sometimes

11. When I read about an incident, I definitely want to find out how This everything happened.

a) Always

c) Sometimes

12. When friends make fun of me, I usually laugh along with everyone and don’t get upset at all.

c) I don’t know

c) Incorrect.

13. When someone speaks rudely to me, I can quickly forget about it.

c) I don’t know

c) Incorrect.

14. I like to “invent” new ways of doing something more than sticking to tried and tested methods.

c) I don’t know

c) Incorrect

15. When I think about something, I like to do it alone, alone.

c) Sometimes

16. I think that I tell lies less often than most people.

c) Something in between

17. I am annoyed by people who cannot make decisions quickly.

c) I don’t know

c) Incorrect

18. Sometimes, although very briefly, I felt hatred towards my parents.

c) I don’t know

19. I would rather reveal my innermost thoughts:

a) my friends

c) I don’t know

c) In my diary

20. I think the opposite word to the opposite of the word “inaccurate” would be:

a) Careless

c) Thorough

c) Approximate

21. I am always full of energy when I need it

c) It's hard to say

22. I am more irritated by people who:

a) They make others blush with their obscene jokes

c) I don’t know

c) They are late for an appointment and make me worry

23. I really like inviting guests and entertaining;

c) I don’t know

c) Incorrect

24. I think that...

a) Some types of work cannot be performed as carefully as others

c) It’s hard to say

c) Any work should be done carefully, if you undertake it at all

25. I always have to fight my shyness.

c) Possibly

26. My friends often:

a) They ask my advice

b) They do both halfway

c) They give me advice

27. If a friend deceives me in small things, I would rather pretend that I didn’t notice it than expose him.

c) Sometimes

28. I like a friend who...

a) Has action and practical interests

c) I don’t know

c) Seriously considers his outlook on life

29. I get irritated when I hear others express ideas that are contrary to those in which I firmly believe.

c) I find it difficult to answer

c) Incorrect

30. I am concerned about my past actions and mistakes.

c) I don’t know

c) Incorrect

31. If I could do both equally well, I would prefer:

a) Play chess

c) It’s hard to say

c) Play town

32. I like sociable campaign people.

c) I don’t know

33. I am so careful and practical that fewer troubles and surprises happen to me than to other people.

c) It's hard to say

34. I can forget about my worries and responsibilities when I need it.

c) Sometimes

35. It is difficult for me to admit that I am wrong.

c) Sometimes

36. At the factory it would be interesting:

a) Work with machines and mechanisms and participate in the main production

c) It's hard to say

c) Talk to others and hire them

37. Which word is not related to the other two:

c) Close

c) Sun

38. What distracts me to some extent, my attention:

a) Annoys me

c) Something in between

c) Doesn't bother

39. If I had a lot of money, I:

a) I would take care not to make myself envious

c) I don’t know

c) I would live without constraining myself in anything

40. Worst punishment for me:

a) Hard work

c) I don’t know

c) Being locked up alone

41. People should demand compliance with moral laws more than they do now

c) Sometimes

42. I was told that I was more of a child:

a) Calm and liked to be left alone

c) I don’t know

c) Cheerful and always active

43. I enjoy practical day-to-day work with various installations and machines.

c) It's hard to say

44.I think that most witnesses tell the truth, even if it makes it difficult for them.

c) It's hard to say

45. If I were talking to a stranger, I would rather:

a) I would discuss political and social views with him

c) I don’t know

c) I would like to hear some new jokes from him

46. I try not to laugh at jokes as loudly as most people do.

c) I don’t know

47. I never feel so unhappy that I want to cry.

c) I don’t know

48. In music I enjoy:

a) Marches performed by military bands

c) I don’t know

c) Typical solo

49. I preferred to spend two summer months faster

a) In the village with one or two friends

c) I don’t know

c) Leading a group in tourist camps

50. Effort expended on making preliminary plans

a) Never superfluous

c) It's hard to say

c) Not worth it

51. The rash actions and statements of my friends do not offend me or make me unhappy.

c) Sometimes

c) Incorrect

52. When I succeed, I find these things easy:

c) Sometimes

c) Incorrect

53. I would rather work:

a) In an institution where I would have to manage people and be among them all the time

c) I find it difficult to answer

c) An architect working on his projects in a quiet room

54. “House” is to “room” as “tree” is to:

c) Plant

55. What I do, I succeed:

c) Sometimes

56. In most cases I:

a) I prefer to take risks

c) I don’t know

c) I prefer to act for sure

57. Some people think that I speak loudly:

a) Most likely this is so

c) I don’t know

c) I think not

58. I admire more:

a) A smart person, but unreliable and fickle

c) It's hard to say

c) A person with average abilities, but able to resist all sorts of temptations

59. I make a decision:

a) Faster than many people

c) I don’t know

c) Slower than many people

60. I am greatly impressed by:

a) Craftsmanship and grace

c) I don’t know

c) Strength and power

61. I believe that I am a cooperative person:

c) Something in between

62. I prefer to talk with a refined, sophisticated person than with a frank and straightforward one:

c) I don’t know

63. I prefer:

a) Resolve issues that concern me personally myself

c) I find it difficult to answer

c) Discuss with my friends

64. If a person does not answer immediately when I say something to him, then I feel that he must have said something stupid:

c) I don’t know

c) Incorrect

65. During my school years I learned the most:

a) In class

c) It's hard to say

c) Reading books

66. I avoid working in public organizations and the associated responsibilities:

c) Sometimes

c) Incorrect

67. When a question is very difficult to solve and requires a lot of effort, I try:

a) Take up another issue

c) I find it difficult to answer

c) Try to solve this issue again

68. I have strong emotions: anxiety, anger, fits of laughter, etc. for seemingly no reason:

c) Sometimes

69. Sometimes my mind doesn't work as clearly as at other times:

c) I don’t know

c) Incorrect

70. I am happy to do a person a favor by agreeing to schedule a meeting with him at a time convenient for him, even if it is a little inconvenient for me.

c) Sometimes

71. I think that the correct number should continue the series 1,2,3,4,5,6,...

72. Sometimes I have short-term attacks of nausea and dizziness for no specific reason:

c) I don’t know

73. I prefer to refuse my order rather than cause unnecessary worry to the waiter:

c) I don’t know

74. I live for today more than other people:

c) I don’t know

c) Incorrect

75. At the party I will have to:

a) Take part in an interesting conversation

c) I find it difficult to answer

c) watch people relax and relax and relax yourself

76. I speak my mind no matter how many people may hear it:

c) Sometimes

77. If I could travel back in time, I would like to meet:

a) with Columbus

c) I don’t know

c) with Shakespeare

78. I have to restrain myself from settling other people’s affairs:

c) Sometimes

79. Working in a store, I would prefer:

a) Design window displays

c) I don’t know

c) Be a cashier

80. If people think badly of me, it doesn’t bother me:

c) It's hard to say

81. If I see that my old friend is cold towards me and avoids me, I usually:

a) I immediately think: “He’s in a bad mood.”

c) I don’t know

c) Worrying about what wrong I did

82. All misfortunes happen because of people:

a) Who try to make changes to everything, although there is already a satisfactory way to resolve these issues

c) I don’t know

c) Who reject new, promising offers

83. I get great satisfaction from reporting local news:

c) Sometimes

84. Neat, demanding people don’t get along with me:

c) Sometimes

c) Incorrect

85. I think that I am less irritable than most people:

c) Sometimes

c) Sometimes

c) Incorrect

87. It happens that all morning I have a reluctance to talk to anyone:

c) Sometimes

c) Incorrect

88. If the hands of a clock meet every 65 minutes measured by an accurate clock, then this clock:

a) They are lagging behind

c) Going correctly

c) They are in a hurry

89. I get bored:

c) Sometimes

90. People say that I like to do things my own way:

c) Sometimes

c) Incorrect

91. I believe that unnecessary worries should be avoided because they tire me:

c) Sometimes

92. At home in my free time, I:

a) Chatting and relaxing

c) I find it difficult to answer

c) Doing things that interest me

93. I am timid and cautious about making friends with other new people:

c) Sometimes

94. I believe that what people say in poetry can also be accurately expressed in prose:

c) It's hard to say

95. I suspect that people who treat me in a friendly manner may turn out to be traitors behind my back:

c) Sometimes

96. I think that even the most dramatic events a year later no longer leave any consequences in the soul:

c) Sometimes

97. I think it would be more interesting to be:

a) Naturalist and work with plants

c) I don’t know

c) Insurance agent

98. I am subject to causeless fear and aversion to certain things, for example, certain animals, places, etc.:

c) Sometimes

99. I like to think about how the world could be better:

c) It's hard to say

100. I prefer games:

a) Where you need to play in a team or have a partner

c) I don’t know

c.) Where everyone plays for himself

101. At night I have fantastic dreams

c) Sometimes

102. If I am left alone in the house, then after a while I feel anxiety and fear:

c) Sometimes

103. I can deceive people with my friendly disposition when in fact I don’t like them:

c) Sometimes

104. Which word does not belong to the other two

Course work

Subject: " Hans Eysenck's theory of personality types "

Introduction

1. Theoretical analysis of the problem of personality traits and types in the theory of G.Yu. Eysenck

1.1 Hierarchical model

1.2 Basic personality types

1.3 Neurophysiological basis of traits and types

2. Measuring Personality Traits

2.1 Diagnostic study of personality traits and types according to the method of G.Yu. Eysenck EPi

2.2 Differences between introverts and extroverts

Conclusion

List of sources used

Introduction

Personality traits are stable characteristics of an individual’s behavior that are repeated in various situations. Mandatory properties of personality traits are their degree of expression in different people, trans-situational nature and potential measurability. Personality traits can be measured using questionnaires and tests specially developed for this purpose. In experimental personality psychology, the most widely studied personality traits are extraversion - introversion, anxiety, rigidity, and impulsivity. Modern research has adopted the point of view that descriptions of personality traits are not enough to understand and predict individual behavioral characteristics, since they describe only general aspects of personality manifestations.

Personality is a set of traits that allows one to predict a person’s actions in a given situation. Associated with both external and internal behavior of the individual. The goal of psychological research on personality is to establish the laws by which people behave in typical social situations.

The most popular factor theories of personality were developed by Hans Eysenck. These theories of personality were focused on empirical research on individual differences in personality.

Theory G.Yu. Eysenck is built according to a hierarchical type and includes a description of a three-factor model of psychodynamic properties (extraversion - introversion, neuroticism and psychoticism). Eysenck refers to these properties as types of the general level of the hierarchical organization of the personality structure. At the next level are traits, below is the level of habitual reactions, actually observed behavior.

Eysenck's significant contribution to the field of factor analysis was the development of criterion analysis techniques, which made it possible to maximally identify specific criterion groups of characteristics, for example, to differentiate a contingent by neuroticism. An equally important conceptual position of Eysenck is the idea that the hereditary factor determines the differences between people in the parameters of the reactivity of the autonomic nervous system, the speed and strength of conditioned reactions, i.e., in genotypic and phenotypic indicators, as the basis of individual differences in the manifestations of neuroticism, psychoticism and extroversion - introversion.

A reactive individual is prone, under appropriate conditions, to the occurrence of neurotic disorders, and individuals who easily form conditioned reactions demonstrate introversion in behavior. People with insufficient ability to form conditioned reactions and autonomous reactivity are more often than others prone to fears, phobias, obsessions and other neurotic symptoms. In general, neurotic behavior is the result of learning, which is based on reactions of fear and anxiety.

Believing that the imperfection of psychiatry and diagnoses is associated with insufficient personal psychodiagnostics, Eysenck developed questionnaires for this purpose and adjusted treatment methods in psychoneurology accordingly. Eysenck tried to determine a person’s personality traits along two main axes: introversion - extraversion (closedness or openness) and stability - instability (level of anxiety).

Thus, the author of these psychological concepts believed that to reveal the essence of personality, it is enough to describe the structure of a person’s qualities. He developed special questionnaires that can be used to describe a person’s individuality, but not his entire personality. It is difficult to predict future behavior based on them, since in real life people’s reactions are far from constant and most often depend on the circumstances that a person encountered at a certain point in time.

The purpose of this course work is to reveal the main provisions of the theory of personality types of G. Eysenck.

The relevance of the topic of the course work is determined by the fact that personality is a special quality that a natural individual acquires in the system of social relations. The dispositional direction in the study of personality is based on two general ideas. The first is that people have a wide range of predispositions to respond in certain ways in different situations (that is, personality traits). This means that people demonstrate a certain consistency in their actions, thoughts and emotions, regardless of the passage of time, events and life experiences. In fact, the essence of personality is determined by those inclinations that people carry throughout their lives, which belong to them and are inseparable from them.

The second main idea of the dispositional direction relates to the fact that no two people are exactly alike. The concept of personality is developed in part by emphasizing the characteristics that distinguish individuals from each other. Indeed, each theoretical direction in personology, in order to remain viable in the market of psychological science, to one degree or another must consider the problem of differences between individuals.

Despite the fact that the exact impact of genetics on behavior is still unclear, a growing number of psychologists believe that Eysenck may be right on this issue.

1 Theoretical analysis of the problem of personality traits and types in theory G.Yu. Eysenck

1.1 Hierarchical model

Using a sophisticated psychometric technique known as factor analysis, G.Yu. Eysenck's theory attempts to show how the basic structure of personality traits influences an individual's observable behavioral responses. For Eysenck, two main parameters are extremely important in personality: introversion-extroversion and stability - neuroticism. The third parameter, called psychoticism, is the strength of the superego. Eysenck also considers it as the main parameter in the structure of personality.

Eyseneck believes that the purpose of psychology is to predict behavior. He also shares the commitment of other psychologists to factor analysis as a way to capture a holistic picture of personality. However, Eysenck uses factor analysis somewhat differently. According to Eysenck, a research strategy should begin with a well-founded hypothesis about some basic trait of interest to the researcher, followed by an accurate measurement of everything that is characteristic of that trait.

Thus, Eysenck's approach is more tightly bound by the framework of theory. Eysenck is convinced that no more than three subtraits (which he calls types) are necessary to explain the majority of human behavioral manifestations. Eysenck attaches much greater importance to genetic factors in the development of an individual. This does not mean that Eysenck denies situational influences or the influence of the environment on a person, but he is convinced that personality traits and types are determined primarily by heredity.

The core of Eysenck's theory is the concept he developed that the elements of personality are arranged hierarchically. Eysenck built a four-level hierarchical system of behavior organization.

The lower level is specific actions or thoughts, an individual way of behaving or thinking, which may or may not be characteristics of the individual. For example, we can imagine a student who starts drawing geometric patterns in his notebook if he fails to complete an assignment. But if his notes are not drawn up and down, we cannot say that such an action has become habitual.

The second level is habitual actions or thoughts, that is, reactions that are repeated under certain conditions. If a student continually works hard on a task until he gets the solution, this behavior becomes his habitual response. Unlike specific reactions, habitual reactions must occur fairly regularly or be consistent. Habitual reactions are identified through factor analysis of specific reactions.

The third level in the hierarchy formulated by Eysenck is occupied by the trait. Eysenck defined a trait as “an important, relatively permanent personal characteristic.” A trait is formed from several interrelated habitual reactions. For example, if a student has the habit of always completing assignments in class and also does not quit any other work until he completes it, then we can say that he has the trait of perseverance. Trait-level behavioral characteristics are obtained through factor analysis of habitual responses, and traits are “defined in terms of the presence of significant correlations between different patterns of habitual behavior.”

The fourth, highest level of organization of behavior is the level of types, or superfactors. A type is formed from several interconnected traits. For example, assertiveness may be associated with feelings of inferiority, poor emotional adjustment, social shyness, and several other traits that together form the introverted type. (Appendix A).

In his schema there are certain supertraits, or types, such as extraversion, that have a powerful influence on behavior. In turn, he sees each of these supertraits as built from several component traits. These composite traits are either more superficial reflections of the underlying type or specific qualities inherent in that type. Finally, traits consist of numerous habitual responses, which in turn are formed from specific responses. Consider, for example, a person who is observed to exhibit a specific response: smiling and extending his hand when meeting another person. If we see him doing this every time he meets someone, we can assume that this behavior is his habitual response to greeting another person. This habitual response may be associated with other habitual responses such as a tendency to talk to other people, attend parties, etc. This group of habitual reactions forms the trait of sociability, which usually exists in conjunction with a predisposition to respond in an active, lively and confident manner. Collectively, these traits make up a supertrait, or type, which Eysenck calls extraversion (Appendix B).

Considering the hierarchical model of personality according to Eysenck, it should be noted that here the word “type” assumes a normal distribution of parameter values on the continuum. Therefore, for example, the concept of extraversion represents a range with upper and lower limits within which people are located in accordance with the severity of this quality. Thus, extraversion is not a discrete quantitative indicator, but a continuum. Therefore, Eysenck uses the term “type” in this case.

1.2 Basic personality types

In early studies, Eysenck identified only two general types or superfactors: extraversion - type (E) and neuroticism - type (N). Subsequently, he defined the third type - psychoticism - (P), although he did not deny the possibility that some other dimensions would be added later. Eysenck viewed all three types as parts of the normal personality structure (Appendix B).

All three types are bipolar, and if extraversion is at one end of factor E, introversion occupies the opposite pole. In the same way, factor N includes neuroticism at one pole and stability at the other, and factor P contains psychoticism at one pole and a strong “super-ego” at the other. The bipolarity of Eysenck's factors does not imply that most people belong to one or the other pole. The distribution of characteristics associated with each type is bimodal rather than unimodal. For example, the distribution of extraversion is very close to normal, similar to the distributions of intelligence and height. Most people end up in the center of a hilly distribution; thus, Eysenck did not believe that people could be divided into several mutually exclusive categories.

Eysenck used the deductive method of scientific research, starting with theoretical constructs and then collecting data that logically corresponded to this theory. Eysenck's theory is based on the use of factor analysis techniques. He himself, however, argued that abstract psychometric research alone is not enough to measure the structure of the properties of the human personality and that the traits and types obtained using factor-analytic methods are too sterile and cannot be assigned any meaning until their biological existence.

Eysenck established four criteria for identifying factors. First, psychometric confirmation of the existence of the factor must be obtained. A natural consequence of this criterion is that the factor must be statistically reliable and verifiable. Other researchers belonging to independent laboratories should also be able to obtain this factor. The second criterion is that the factor must have the property of inheritance and satisfy the established genetic model. This criterion excludes learned characteristics, such as the ability to imitate the voices of famous people or political and religious beliefs. Third, the factor must make sense from a theoretical point of view.

The final criterion for the existence of a factor is its social relevance, that is, it must be shown that the mathematically derived factor has a relationship (not necessarily strictly causal) to social phenomena, for example, such as drug abuse, a tendency to get into unpleasant situations, outstanding achievements in sports, psychotic behavior, crime, etc.

Eysenck argued that each of the types he identified meets these four criteria for identifying personal characteristics.

First, there is rigorous psychometric evidence for the existence of each factor, especially the E and N factors.

Factor P (psychotism) appeared in Eysenck’s works later than the first two, and there is still no equally reliable evidence for it from other scientists. Extraversion and neuroticism (or anxiety) are the main types or superfactors in almost all factor-analytic studies of personality traits.

Secondly, Eysenck argued that there is a strict biological basis for each of these three superfactors. At the same time, he argued that traits such as social conformity and conscientiousness, which are included in the Big Five taxonomy, have no biological basis.

Third, all three types, especially E and N, make sense theoretically. Jung, Freud, and other theorists noted that factors such as extraversion/introversion and anxiety/emotional stability have a significant influence on behavior. Neuroticism and psychoticism are not characteristics exclusively of pathological individuals, although mentally ill individuals do score higher on scales measuring these two factors than normal individuals. Eysenck proposed a theoretical justification for factor P (psychoticism), based on the hypothesis that the characteristics of mental health in the bulk of people are distributed continuously. At one end of the hill-shaped distribution are the exceptionally healthy traits of altruism, good social adjustment, and empathy, and at the other end are traits such as hostility, aggressiveness, and schizophrenic tendencies. A person, according to his characteristics, can be at any point on this continuous scale, and no one will perceive him as mentally ill. Eysenck, however, developed the diathesis-stress model of mental illness, which holds that some people are more vulnerable to illness because they have some genetic or acquired weakness that makes them more susceptible to mental illness.

Eysenck hypothesizes that people whose characteristics fall toward the healthy end of the P-scale will be resistant to psychotic breaks, even during periods of great stress. On the other hand, for those closer to the unhealthy edge, even minimal stress can trigger a psychotic reaction. In other words, the higher the psychoticism score, the less severe stress is necessary for the occurrence of a psychotic reaction.

Fourth, Eysenck has repeatedly demonstrated that his three types are associated with social issues such as drugs, sexual behavior, crime, cancer and heart disease prevention, and creativity.

All three superfactors—extraversion, neuroticism, and psychoticism—are heavily influenced by genetic factors. Eysenck argued that about three-quarters of the variation in each of the three superfactors is explained by heredity and only about one-quarter by environmental conditions. He collected a lot of evidence of the importance of the biological component in the formation of personality. First, almost identical factors have been found in people around the world. Secondly, it has been proven that a person's position relative to the three dimensions of personality tends to persist for a long time. And third, studies of twin pairs have shown that identical twins exhibit significantly more similar characteristics than fraternal twins of the same sex raised together, which may support the determining role of genetic factors in the manifestation of individual differences between different people.

1.3 Neurophysiological basis of traits and types

The most fascinating aspect of Eysenck's theory is his attempt to establish a neurophysiological basis for each of the three supertraits or personality types. Introversion-extroversion is closely related to cortical activation levels, as shown by electroencephalographic studies. Eysenck uses the term “activation” to denote the degree of arousal, varying in value from a lower limit (for example, sleep) to an upper limit (for example, a state of panic). He believes that introverts are extremely excitable and therefore highly sensitive to incoming stimulation - for this reason they avoid situations that affect them too much. Conversely, extroverts are not sufficiently excitable and therefore insensitive to incoming stimulation; accordingly, they are constantly on the lookout for situations that might arouse them.

Eysenck suggests that individual differences in stability-neuroticism reflect the strength of the autonomic nervous system's response to stimuli. In particular, he links this aspect to the limbic system, which influences motivation and emotional behavior. People with high levels of neuroticism tend to respond to painful, unfamiliar, anxiety-inducing, and other stimuli more quickly than more stable individuals. Such individuals also exhibit longer-lasting reactions that continue even after the disappearance of stimuli than individuals with a high level of stability.

As for studies devoted to identifying the basis of psychotism, they are in the search stage. However, as a working hypothesis, Eysenck links this aspect with the system that produces androgens (chemical substances produced by the endocrine glands, which, when released into the blood, regulate the development and maintenance of male sexual characteristics). However, too little empirical research has been conducted in this area to confirm Eysenck's hypothesis about the relationship between sex hormones and psychoticism.

The neurophysiological interpretation of aspects of personality behavior proposed by Eysenck is closely related to his theory of psychopathology. In particular, different types of symptoms or disorders may be attributed to the combined influence of personality traits and nervous system functioning. For example, a person with a high degree of introversion and neuroticism is at very high risk of developing painful anxiety conditions, such as obsessive-compulsive disorder, as well as phobias. Conversely, a person with high levels of extraversion and neuroticism is at risk for psychopathic (antisocial) disorders. However, Eysenck hastens to add that mental disorders are not automatically the result of genetic predisposition. Genetically inherited is a person’s predisposition to act and behave in a certain way when faced with certain situations. Thus, Eysenck's belief in the genetic basis of various types of mental disorders is combined with an equal conviction that environmental factors can to some extent modify the development of such disorders.

2 . Measuring Personality Traits

2.1 Diagnostic study of personality traits and types according to the method of G.Yu. Eysenck EPi

G. Eysenck repeatedly pointed out in his works that his research was caused by the imperfection of psychiatric diagnoses. In his opinion, the traditional classification of mental illness should be replaced by a measurement system that represents the most important personality characteristics. At the same time, mental disorders are, as it were, a continuation of the individual differences observed in normal people

Eysenck constructed a variety of self-esteem questionnaires to measure individual differences in the three super personality traits. The most recent of these is the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire. Samples of individual EPQ items are presented in Table 1. It should be noted that the questionnaire contains items relevant to these three factors that form the personality structure. In addition, the EPQ includes a lie scale to assess an individual's tendency to falsify answers in order to present themselves in a more attractive light. The Junior EPQ questionnaire was also compiled for testing children aged 7–15 years.

Table 1 – Examples of items from the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire

| Extraversion-Introversion | |

| 1. Do you like to be in society? | Not really |

| 2. Do you like to communicate with people? | Not really |

| 3. Would you call yourself lucky? | Not really |

| Stability-Instability | |

| 1. Does your mood often change dramatically? | Not really |

| 2. Are you an excitable person? | Not really |

| 4. Are you often upset? | Not really |

| Psychopathy | |

| 1. Do good manners and neatness matter to you? | Not really |

| 2. Do you try not to be rude to people? | Not really |

| 3. Do you like to collaborate with others? | Not really |

| Lie scale | |

| 1. Do you like to laugh sometimes at obscene jokes? | Not really |

| 2. As a child, did you always immediately do what you were told, without grumbling or complaining? | Not really |

Eysenck is convinced that his two main type criteria of introversion - extraversion and stability - neuroticism have been empirically confirmed in the work of several researchers who have used many other personality tests. Much of the evidence to support this view comes from studies of behavioral differences between extroverts and introverts.

Each personality type is naturally conditioned; one cannot talk about “good and bad” temperaments; one can only talk about different modes of behavior and activity, about the individual characteristics of a person. Each person, having determined the type of his temperament, can more effectively use his positive traits.

Extroverts usually have external charm, are straightforward in their judgments, and, as a rule, are guided by external assessment. They cope well with work that requires quick decision-making. Describing a typical extrovert, the author notes his sociability and outward-looking personality, a wide circle of acquaintances, and the need for contacts. A typical extrovert acts on the spur of the moment, is impulsive, and has a quick temper. He is carefree, optimistic, good-natured, cheerful. Prefers movement and action, tends to be aggressive. Feelings and emotions are not strictly controlled, and he is prone to risky actions. You can't always rely on him.

Neuroticism is emotional stability. Characterizes emotional stability or instability (emotional stability or instability). Neuroticism, according to some data, is associated with indicators of lability of the nervous system. Neuroticism is expressed in extreme nervousness, instability, poor adaptation, a tendency to quickly change moods (lability), feelings of guilt and anxiety, preoccupation, depressive reactions, absent-mindedness, instability in stressful situations. Neuroticism corresponds to emotionality and impulsiveness; unevenness in contacts with people, variability of interests, self-doubt, pronounced sensitivity, impressionability, tendency to irritability.

A neurotic personality is characterized by inappropriately strong reactions in relation to the stimuli that cause them. Individuals with high scores on the neuroticism scale may develop neurosis in unfavorable stressful situations.

Table 2 – matrix typology of personalities according to the EPQ method

Using this matrix, it is easy to determine whether a person belongs to one of nine personality types, using combinations of the severity of extraversion and neuroticism.

Each personality type corresponds to the following external manifestations:

1. Choleric (X) – aggressive, hot-tempered, changing his views / impulsive.

2. Choleric-sanguine (CS) type - optimistic, active, extroverted, sociable, accessible.

3. Sanguine (S) – talkative, quick to react, relaxed, lively.

4. Sanguine-phlegmatic (SP) type – carefree, leading, stable, calm, balanced.

5. Phlegmatic (F) – reliable, self-controlled, peaceful, reasonable.

6. Phlegmatic-melancholic (FM) type – diligent, passive, introverted, quiet, unsociable.

7. Melancholic (M) – reserved, pessimistic, sober, rigid.

8. Melancholic-choleric (MX) type – conscientious, capricious, neurotic, touchy, restless.

The table shows the values of the extraversion-introversion, neuroticism-stability scales according to the EPQ method. By substituting the average values on two basic scales, as well as the extreme manifestations of traits in scores, it is not difficult to obtain a matrix that allows you to determine the personality type using the EPI method.

For individual diagnostics, this matrix helps determine whether a person belongs to a certain type, on the basis of which a psychological portrait of the individual can be built. In addition, the matrix distribution of types allows us to portray social communities.

Matrix and profile portraits make it easy to compare typological portraits of different social groups of people, and the graphic representation of profiles provides clarity for comparison.

Conclusion

In the course of studying personality types according to the theory of G.Yu. Eysenck, the following theoretical problems were consistently solved: an analysis of the problem of personality traits and types was carried out, the basic concepts and principles of the theory of personality types were identified, personality types in the theory of G.Yu. Eysenck.

Theoretical analysis showed that Eysenck's theory of personality types is based on factor analysis. His hierarchical model of personality structure includes types, personality traits, habitual reactions, and specific reactions. Types are continuums on which the characteristics of individuals are located between two extremes. Eysenck emphasizes that personality types are not discrete and that most people do not fall into extreme categories.

Hans Eysenck's type theory was developed on the basis of the mathematical apparatus of factor analysis. This method assumes that people have a variety of relatively constant personal qualities, or traits, and that these traits can be measured using correlational studies. Eysenck used the deductive method of scientific research, starting with theoretical constructs and then collecting data that logically corresponded to this theory.

Eysenck established four criteria for identifying factors. First, psychometric confirmation of the existence of the factor must be obtained. The second criterion is that the factor must have the property of inheritance and satisfy the established genetic model. Third, the factor must make sense from a theoretical point of view. The final criterion for the existence of a factor is its social relevance, that is, it must be shown that the mathematically derived factor has a relationship (not necessarily strictly causal) to social phenomena.

Eysenck formulated the concept of a hierarchical four-level model of human personality. The lower level is specific actions or thoughts, an individual way of behaving or thinking, which may or may not be characteristics of the individual. The second level is habitual actions or thoughts that are repeated under certain conditions. The third level is personality traits, and the fourth, the highest level of behavior organization, is the level of types, or superfactors.

Extraversion is characterized by sociability and impulsiveness, introversion by passivity and thoughtfulness, neuroticism by anxiety and forced habits, stability by the absence of such, psychoticism by antisocial behavior, and the superego by a tendency toward empathy and cooperation.

Eysenck placed special emphasis on the biological components of personality. According to his theory, environmental influences are practically unimportant in shaping personality. In his opinion, genetic factors have a much greater influence on subsequent behavior than childhood impressions.

Eysenck's theory of personality types is based on factor analysis. His hierarchical model of personality structure includes types, personality traits, habitual reactions, and specific reactions. Types are continuums on which the characteristics of individuals are located between two extremes. Eysenck emphasizes that personality types are not discrete and that most people do not fall into extreme categories.

Eysenck sees only two main types (subtraits) underlying the personality structure: introversion-extroversion, stability-neuroticism. The obvious behavioral features that result from combinations of these two types are considered. For example, people who are both introverted and stable tend to be in control of their actions, while extroverts who are stable tend to act carefree. Eysenck argues that individual differences in these two subtraits are closely related to the neurophysiological characteristics of the human body. Eysenck attaches much more importance to the genetic basis of personality traits than other personologists.

Eysenck, in addition to the EPi questionnaire, several more questionnaires to assess the main subtraits that underlie his hierarchical personality model.

Theories of personality based on factor analysis reflect modern psychology's interest in quantitative methods and, in turn, are reflected in a huge number of specially organized studies of personality.

In the vast number of applied studies that Eysenck carried out to prove his theory, most often together with specialists in the relevant fields, the importance of differences in these factors was shown in crime statistics, in mental illness, in susceptibility to accidents, in the choice of professions, in the severity of level of achievements, in sports, in sexual behavior, etc.

Eysenck's tireless efforts to create a holistic picture of personality are admirable. Many psychologists consider him a first-class specialist, extremely fruitful in his attempts to create a scientifically based model of personality structure and functioning. Throughout Eysenck's work, he consistently emphasized the role of neurophysiological and genetic factors in explaining individual behavioral differences. In addition, he argues that an accurate measurement procedure is the cornerstone of constructing a convincing theory of personality. Also noteworthy are his contributions to research in criminology, education, psychopathology, and behavior change. Overall, it seems logical to conclude that the popularity of Eysenck's theory will further increase and that scientists will continue to attempt to improve and expand his theory of personality traits at both the theoretical and empirical levels.

List of sources used

1. Granovskaya R.M. Elements of practical psychology [Text] / R.M. Granovskaya – 3rd ed., with amendments. and additional – St. Petersburg: Svet, 1997 – 608 p. – ISBN– 5–9268–0184–2

2. Danilova N.N., Physiology of higher nervous activity [Text] / N.N. Danilova, A.L. Krylova - M.: Educational literature, 1997. - 432 pp. ISBN 5–7567–0220

3. Ilyin E.P. Differential psychophysiology [Text] / E.P. Ilyin - St. Petersburg: Peter, 2001. - 464 p. ISBN: 933–5–04–126534–3

4. Kretschmer E. Body structure and character [Text]/E. Kretschmer Per. with him. / Afterword, comment. S.D. Biryukova. – M.: Pedagogy-Press, 1995. – 607 pp. ISBN: 978–5–04–006635–3

5. Krupnov A.I. Dynamic features of activity and emotionality of temperament [Text] / A.I. Krupnov // Psychology and psychophysiology of activity and self-regulation of human behavior and activity. – Sverdlovsk, 1989 ISBN 81–7305–192–5.

6. Morozov A.V. Business psychology [Text] / A.V. Morozov: Course of lectures: Textbook for higher and secondary specialized educational institutions. – St. Petersburg: Soyuz Publishing House, 2000. – 576 p. ISBN.: 5–8291–0670–1

7. Psychological diagnostics [Text]: Textbook / Ed. K.M. Gurevich and E.M. Borisova. – M.: Publishing house URAO, 1997. – 304 pp. ISBN. 9785699300235

8. Raigorodsky D.Ya. (editor-compiler). Practical psychodiagnostics [Text] / D.Ya. Raigorodsky: Methods and tests. Tutorial. – Samara: Publishing House “BAKHRAKH”, 1998. – 672 pp. ISBN.: 978–5–94648–062–8.

9. Rusalov V.M. Temperament structure questionnaire [Text]/ V.M. Rusalov: Methodological manual. – M., 1990. ISBN 5–89314–063-X

10. Kjell L., Theories of personality (Basic principles, research and application) [Text] / L. Kjell, D. Ziegler. – St. Petersburg. Peter Press, 1997. – 608 p. ISBN.: 5–88782–412

11. Shevandrin N.I. Psychodiagnostics, correction and personality development [Text]/ N.I. Shevandrin. – M.: VLADOS, 1998. – 512 p. ISBN.: 5–87065–066–6.

Granovskaya R.M. Elements of practical psychology [Text] / R.M. Granovskaya – 3rd ed., with amendments. and additional – St. Petersburg: Svet, 1997 – 608 s.

Ilyin E.P. Differential psychophysiology [Text] / E.P. Ilyin – St. Petersburg: Peter, 2001. – 464 p.

Kretschmer E. Body structure and character [Text]/E. Kretschmer Per. with him. / Afterword, comment. S.D. Biryukova. – M.: Pedagogy-Press, 1995. – 607

Psychological diagnostics [Text]: Textbook / Ed. K.M. Gurevich and E.M. Borisova. – M.: Publishing house URAO, 1997. – 304 p.

Shevandrin N.I. Psychodiagnostics, correction and personality development [Text]/ N.I. Shevandrin. – M.: VLADOS, 1998. – 512

Rusalov V.M. Temperament structure questionnaire [Text]/ V.M. Rusalov: Methodological manual. - M., 1990

Course work

Subject: " Hans Eysenck's theory of personality types "

Introduction

1. Theoretical analysis of the problem of personality traits and types in the theory of G.Yu. Eysenck

1.1 Hierarchical model

1.2 Basic personality types

1.3 Neurophysiological basis of traits and types

2. Measuring Personality Traits

2.1 Diagnostic study of personality traits and types according to the method of G.Yu. Eysenck EPi

2.2 Differences between introverts and extroverts

Conclusion

List of sources used

Introduction

Personality traits are stable characteristics of an individual’s behavior that are repeated in various situations. Mandatory properties of personality traits are their degree of expression in different people, trans-situational nature and potential measurability. Personality traits can be measured using questionnaires and tests specially developed for this purpose. In experimental personality psychology, the most widely studied personality traits are extraversion - introversion, anxiety, rigidity, and impulsivity. Modern research has adopted the point of view that descriptions of personality traits are not enough to understand and predict individual behavioral characteristics, since they describe only general aspects of personality manifestations.

Personality is a set of traits that allows one to predict a person’s actions in a given situation. Associated with both external and internal behavior of the individual. The goal of psychological research on personality is to establish the laws by which people behave in typical social situations.

The most popular factor theories of personality were developed by Hans Eysenck. These theories of personality were focused on empirical research on individual differences in personality.

Theory G.Yu. Eysenck is built according to a hierarchical type and includes a description of a three-factor model of psychodynamic properties (extraversion - introversion, neuroticism and psychoticism). Eysenck refers to these properties as types of the general level of the hierarchical organization of the personality structure. At the next level are traits, below is the level of habitual reactions, actually observed behavior.

Eysenck's significant contribution to the field of factor analysis was the development of criterion analysis techniques, which made it possible to maximally identify specific criterion groups of characteristics, for example, to differentiate a contingent by neuroticism. An equally important conceptual position of Eysenck is the idea that the hereditary factor determines the differences between people in the parameters of the reactivity of the autonomic nervous system, the speed and strength of conditioned reactions, i.e., in genotypic and phenotypic indicators, as the basis of individual differences in the manifestations of neuroticism, psychoticism and extroversion - introversion.

A reactive individual is prone, under appropriate conditions, to the occurrence of neurotic disorders, and individuals who easily form conditioned reactions demonstrate introversion in behavior. People with insufficient ability to form conditioned reactions and autonomous reactivity are more often than others prone to fears, phobias, obsessions and other neurotic symptoms. In general, neurotic behavior is the result of learning, which is based on reactions of fear and anxiety.

Believing that the imperfection of psychiatry and diagnoses is associated with insufficient personal psychodiagnostics, Eysenck developed questionnaires for this purpose and adjusted treatment methods in psychoneurology accordingly. Eysenck tried to determine a person’s personality traits along two main axes: introversion - extraversion (closedness or openness) and stability - instability (level of anxiety).

Thus, the author of these psychological concepts believed that to reveal the essence of personality, it is enough to describe the structure of a person’s qualities. He developed special questionnaires that can be used to describe a person’s individuality, but not his entire personality. It is difficult to predict future behavior based on them, since in real life people’s reactions are far from constant and most often depend on the circumstances that a person encountered at a certain point in time.

The purpose of this course work is to reveal the main provisions of the theory of personality types of G. Eysenck.