Read "the story of God" online. Karen Armstrong - The Story of God. Thousand-year quest in Judaism, Christianity and Islam The history of God Armstrong

This book is not dedicated to the history of the ineffable existence of God Himself, not subject to either time or change; This is the history of the human race's ideas about God - starting from Abraham and up to the present day.

Karen Armstrong - The History of God - The Millennial Quest in Judaism, Christianity and Islam

Publisher: Sofia, 2004

The human idea of God has its own history, because in different eras different peoples perceived Him differently. The concept of God held by one generation may be completely meaningless to another. The words “I believe in God” are devoid of objective content. Like any other statement, they are filled with meaning only in the context when uttered by a member of a particular society.

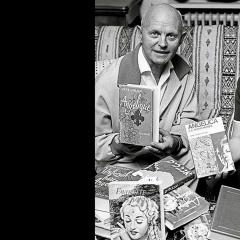

A well-known historian of religion, the Englishwoman Karen Armstrong is endowed with rare virtues: enviable scholarship and a brilliant gift for speaking simply about complex things. She created a real miracle, covering in one book the entire history of monotheism - from Abraham to the present day, from ancient philosophy, medieval mysticism, spiritual quests of the Renaissance and Reformation up to the skepticism of the modern era.

Karen Armstrong - The History of God - The Millennial Quest in Judaism, Christianity and Islam - Contents

1. IN THE BEGINNING…

2. ONE GOD

3. LIGHT TO THE PAGENTS

4. TRINITY: GOD OF THE CHRISTIAN

5. UNITY: GOD OF THE MUSLIMS

6. GOD OF PHILOSOPHERS

7. GOD OF MYSTICS

8. GOD OF THE REFORMERS

9. ENLIGHTENMENT

10. IS GOD DEAD?

11. LONG LIVE GOD?

Karen Armstrong - The Story of God - Foreword

As a child, I had strong religious beliefs and a fairly weak faith in God. There is a difference between beliefs (where we accept certain statements on faith) and real faith (when we rely completely on them). Of course, I believed that God exists. I believed in the real presence of Christ in the sacrament, in the effectiveness of the sacraments, and in the eternal torment awaiting sinners. I believed that purgatory was a very real place. However, I cannot say that these beliefs in religious dogmas about the nature of a higher reality gave me a genuine sense of the grace of earthly existence. When I was a child, Catholicism was mostly a fearful creed. James Joyce described it accurately in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man; I also listened to my course of sermons about fiery hell. To tell the truth, the torments of hell looked much more convincing than God.

The underworld was easily comprehended by the imagination, but God remained an unclear figure and was defined not so much by visual images as by speculative reasoning. At the age of eight, I had to memorize the answer to the question “Who is God?” from the catechism: “God is the Supreme Spirit, the one Self-existent and infinite in all perfections.” Of course, I didn’t understand the meaning of these words. I must admit that they still leave me indifferent: such a definition has always seemed to me too dry, pompous and arrogant. And while working on this book, I came to the conclusion that it was also wrong.

As I grew up, I realized that religion is not only about fear. I read the lives of saints, the works of metaphysical poets, the poems of Thomas Eliot and some of the works of mystics - from those who wrote more simply. The liturgy began to captivate me with its beauty. God still remained distant, but I felt that He could still be reached and that touching Him would instantly transform the entire universe. For this reason I joined one of the spiritual orders. After becoming a nun, I learned a lot more about faith.

I immersed myself in apologetics, theological studies, and church history. I studied the history of monastic life and embarked on detailed discussions about the charter of our order, which we were all obliged to know by heart. Oddly enough, God did not play such a big role in all this. The main attention was paid to minor details, the particulars of faith. During prayer, I desperately forced myself to concentrate all my thoughts on meeting with God, but He either remained a stern taskmaster, vigilantly monitoring any violation of the rules, or - what was even more painful - slipped away altogether. The more I read about the mystical delights of the righteous, the more saddened I was by my own failures. I bitterly admitted to myself that even those rare religious experiences that I had could well have been the fruit of my own imagination, the result of a burning desire to experience them.

Religious feeling is often an aesthetic response to the charm of liturgy and Gregorian chant. One way or another, nothing happened to me that came from outside. I have never felt those glimpses of God's presence that the mystics and prophets spoke about. Jesus Christ, about whom we spoke much more often than about God himself, seemed to be a purely historical figure, inseparable from the era of late antiquity. To make matters worse, I began to increasingly doubt certain church doctrines. How can one be sure, for example, that Jesus was God incarnate? What does this idea even mean? What about the doctrine of the Trinity? Is this complex - and extremely controversial - concept actually found in the New Testament? Perhaps, like many other theological constructs, the Trinity was simply invented by the clergy centuries after the execution of Jesus in Jerusalem?

Eventually, though not without regret, I withdrew from religious life, a step that immediately freed me from the burden of failure and feelings of inferiority. I felt my faith in God weakening. To tell the truth, He never left a significant mark on my life, although I tried with all my might to do so. And I felt neither guilt nor regret - God became too distant to seem something real. However, I retained my interest in religion itself. I have produced a number of television programs dealing with the early history of Christianity and religious experiences. As I studied the history of religion, I became increasingly convinced that my earlier fears were well founded.

Doctrines that were accepted without reasoning in youth were indeed invented by people and perfected over many centuries. Science has clearly eliminated the need for a Creator, and Bible scholars have proven that Jesus never claimed divinity. During epileptic seizures, I had visions, but I knew that these were only symptoms of neuropathology; Perhaps the mystical delight of saints and prophets should also be attributed to the quirks of the psyche? God began to seem to me like some kind of insanity that the human race has long outgrown.

It's time to write a review of a book that was published in 1993, and in Russian, it seems, in 2004. However, “The History of God” regularly goes through one reprint after another. The latter was published just in 2014 and is now sold in many stores (but the text of the book is also available on the Internet, so there is no need to spend money). This is not an academic work, but you can’t call it chewing gum for the mass consumer either. Therefore, such a long life of a book (by the standards of the current information society) is already remarkable. This work is worthy of attention.

So, the full name is “The History of God. 4000 years of quest in Judaism, Christianity and Islam." The author is Karen Armstrong, a former nun who left the monastery due to doubts about religion. The book's biting title is probably a tribute to its commercial hit. Armstrong herself clarifies in the preface: This book is not dedicated to the history of the ineffable existence of God himself, not subject to either time or change; This is the history of the human race's ideas about God - from Abraham to the present day. The approach itself is indicative: the historicity and evolutionary nature of the idea of God is already intolerable for religious consciousness and turns it from an ontological absolute into a socio-psychological fact, making the divine derivative of the human.

However, Armstrong is not so consistent in her conclusions, but even though she is not a materialist, her research method is dialectical; “The History of God” is not just a chronology of religious teachings, but the dynamics of their development, united by an internal logic that is completely natural and, in its own way, tragic for the protagonist of the story. Although the author’s concept is not new for historians and religious scholars, it is useful for us, ordinary people, to remember that for thousands of years people believed not only in different things, but also differently:

“The words “I believe in God” are devoid of objective content. Like any other statement, they are filled with meaning only in the context when uttered by a member of a particular society. Thus, behind the concept of “god” there is not at all hidden some unchanging idea. On the contrary, it contains a wide range of meanings, some of which may completely negate each other and even turn out to be internally contradictory.”

The subject of the book is almost exclusively the history of the Abrahamic religions. It is unfortunate that Armstrong devotes less than ten pages to the era “before Abraham,” starting the story with the theory of “primitive monotheism” (or proto-monotheism), which today is considered, to put it mildly, controversial and unproven. Of course, the author is free to choose the scope of the study. But this approach somewhat distorts the perspective, especially for the unprepared reader: religion appears on the scene almost out of nowhere, for no reason, and, accordingly, without proper consideration of the origins of religious feeling. “The Story of God” is like a painting where a temple is meticulously and realistically depicted - but not standing on the ground, but suspended in the air. The reader learns a lot What thought about God in different eras, but much less about why.

And this is not just a chosen perspective, but a worldview position. Armstrong examines religious concepts from the inside, little (and rather superficially) touching on their material and social conditioning. The very question of the origin of religion is removed by the statement that religious feeling naturally inherent to a person. However, using her own method, we have the right to object that this original religious feeling, even at its core, has little in common with the present one. Having said that religious faith has accompanied man throughout his entire history, it is necessary to clarify that it has changed its character more than once, so that the faith that Armstrong herself adheres to bears little resemblance to the faith of a medieval person, and certainly does not in any way resemble a religious feeling archaic man.

The author, however, objects, but too ad hominem: Already in the most ancient beliefs, that sense of miracle and mystery is manifested, which still remains an integral part of human perception of our beautiful and terrible world.

Even if so, “miracle and mystery” are not enough to establish the identity of an object. This feeling lives both in art and, partly, in scientific research. However, it seems to us that imposing excessive mystery on archaic beliefs is a considerable sin against the historical approach. Yes, they are mysterious to us today, thousands of years later, when we put together their mosaic from scattered fragments. But how did they feel to living carriers? After all, archaic myth was not a means of obscuring, but, on the contrary, structuring and interpreting the world for the primary coordination of the collective. Moreover, the myth was the only one a picture of the world that was possible in a primitive society, completely dependent on the elemental forces of nature.

Strictly speaking, calling such a worldview “religious” would be incorrect. The main feature of archaic consciousness was its totality, indivisibility: the primitive world did not know the dichotomy of the material and the ideal in the sense of classical philosophy. An image (verbal or pictorial) not only meant an object, it also was object. Divine and demonic forces were thought of as completely material (and, in fact, they were personified), and ritual was part of the practical support of everyday life. The gods of early antiquity were completely devoid of sublimity, shocking the modern reader with extreme naturalism, rudeness and immorality. Accordingly, they were perceived not as a “miracle and mystery,” but as powerful figures with whom, through ritual, certain mutually beneficial relationships were created that imposed obligations on both parties. Thus, a statue of a god who did not fulfill its functions could be put on a starvation ration as punishment, deprived of sacrifices, or even flogged. Archaic consciousness did not remove the gods into transcendental distances; the divine lived Here and now.

Such a picture of the world was, of course, to a certain extent conditional, but the point is precisely that human thought at that time had not yet developed the means to express and define this convention; and what is inexpressible through language cannot be realized.

This stage of the development of religion is recorded in written sources of the 3rd millennium BC. Ritual is inseparable from practical activity, and such activity itself often appears in the form of ritual. However, by the beginning of the second millennium, as the first civilizations of the Fertile Crescent accumulated knowledge and ensured themselves relative independence from the forces of nature, a corresponding ideological turn was brewing. The practical expediency of the cult ritual is questioned (as exemplified by, say, the poems “Babylonian Theodicy” and “The Innocent Sufferer,” prototypes of the biblical “Book of Job”). God urgently needed to find a new place for himself in the universe - and the human soul became such a place for the next three millennia. The starting point for the new relationship between man and God is the Jewish myth of Abraham, the events of which date back to approximately the 20th-18th centuries. BC e. From this moment Karen Armstrong's story begins.

Analyzing the layers of the Old Testament at different times, she proves that the essence of this myth is not at all the birth of monotheism. It is quite possible that the god of Abraham is not even identical to the Old Testament god, but was just one of the Middle Eastern deities that later merged into a single image of Yahweh. The novelty here is different. The archaic heavens are organized horizontally: the gods, of course, are at enmity with each other, but do not deny each other, religious discord is unknown to antiquity - here God declares himself not as the only one, but as exceptional. It can be said that through the myth of Abraham, God for the first time directly establishes a connection with the personality of man, tames his. Now it is not enough to take it into account as an abstract fact; he must become value.

It is clear that this became necessary precisely when the divine took the first step away from the material world. Ritual as a form of communication with the deity still dominates; only in the 8th century. BC e., through the mouth of the prophet Hosea, the Jewish god will proclaim: “I want mercy, not sacrifice!” - that is, having finally abandoned earthly materiality, it will assume the exclusive right to sanction morality.

But we will not retell the text of the book. Anyone who wants to read it. She scrupulously analyzes the formation of the three great Abrahamic religions, seriously and fascinatingly talks about the theological concepts within each of them, drawing parallels that prove that the emergence of certain religious views is not an accidental (and certainly not “divinely inspired”) phenomenon, but a product of “human , too human” sociocultural realities.

Armstrong is extremely skeptical of religious philosophy, that is, fruitless attempts to rationally, rationally comprehend and justify the existence of God. She repeats many times: we know absolutely nothing about God, his existence is unprovable, and his essence is unknowable. Finally, she recognizes the very idea of the “anthropomorphic” (not physically, of course, but mentally), i.e., personal God is unacceptable, unsatisfactory, and, moreover, harmful. (Strictly speaking, it is not the idea itself that is harmful, but its application in social practice. This is the whole point: people have been killing and oppressing each other for thousands of years under a variety of slogans, without hesitating, if necessary, to invent them from scratch: trifling discrepancies that only yesterday coexisted peacefully each other, turn into a reason for a bloodbath - ideology is important, it influences social relations, but not creates their.)

Here we must acknowledge another indisputable merit of the author: Armstrong has sufficient honesty not to hide the problems facing religious consciousness. In essence, the entire history of God is the history of these problems. We see how, from century to century, God inexorably dematerializes, abstracts, and hides in the transcendent. Finally, by the beginning of the twentieth century, the author has to state the “death of God,” albeit with a question mark (although today, in the era of ISIS and “spiritual bonds,” such a statement seems, alas, less justified than in 1993, when the book was written) . Despite all the academic correctness, she is far from dispassionate in her assessments, and the recognition of the inappropriateness of religious consciousness in the modern world, which has lost God, is clearly imbued with the pain of the experience. In the face of her sincerity, I don’t even want to be ironic about the unsightly results of 4,000 years of quest. It finds no way out either in fundamentalism (which it resolutely condemns without regard to the outer attire - Islamic, Christian, or Jewish) or in dogmatic scholasticism. But, it must be said, not in atheism either - although he largely recognizes the correctness of atheistic criticism of traditional religious views and leaves open the question of the results of the “experiment” to create a secularized society: “if in our empirical age the previous ideas about God cease to be useful, they , of course, will be discarded."

And, moreover, the sad story of God for Armstrong does not at all mean a break with religious faith, albeit a very peculiar one. But what then remains of God - a non-personal God devoid of any anthropomorphism, ineffable and ineffable by definition, who has disappeared without a trace in the transcendental fog, about which one cannot even say whether he exists or not? And should I be worried about this shadow? Following the above words, she continues:

“On the other hand, until now people have always created new symbols, which became the focus of their spirituality. At all times, man himself created what he believed in, since he absolutely needs a feeling of miracle and inexpressible fulfillment of being. All the characteristic signs of modernity - the loss of meaning and purpose, alienation, the collapse of foundations, violence - indicate, apparently, that now that we are no longer intentionally trying to create for ourselves either a belief in “God” or anything else (which, Actually, the difference is what to believe in?), an increasing number of people are falling into complete despair.”

One cannot but agree with this diagnosis. But what is the medicine? According to Karen Armstrong, the path between the Scylla of despair and the Charybdis of fanaticism can run through “mystical agnosticism” - that is, the extra-rational experience of a divine miracle through the imagination: a religious feeling must turn into a fact of the individual psyche of the believer - in other words, a person himself must create God within yourself. Indeed, the psychic fact of religious experience cannot be refuted. As Bertrand Russell said, you can have sincere feelings for a fictional character, but this only implies the authenticity of the feeling, and not the authenticity of the hero. The trouble, however, is that religion as a social phenomenon is created precisely by the sum of individual faiths, and how successful “mystical agnosticism” will differ from other religious teachings is not clear. Armstrong herself admits that such a solution is unlikely to become widespread: the path to mystical enlightenment is long and difficult...

And is it necessary? Few, negligible, arguments are given by Armstrong to justify his “residual religiosity”: the notorious “sense of wonder and mystery”, the fear of emptiness and loneliness, the divine nature of inspiration... But in none of these points are religious or mystical experiences indispensable condition. It is wrong to identify a secularized society with wingless pragmatism: although this is exactly the example we have before us today, we know of other examples when creative impulses, self-sacrifice and the highest ideals rose to heights never before seen in the history of mankind. If anyone wants to call this the sickening word “spirituality,” it’s okay; by and large, it’s appropriate: after all, we’re talking about liberating a person from a dull mess of utilitarian values.

By the end of the second millennium, the feeling that the familiar world was becoming a thing of the past became intensified - with these words the last chapter of “The History of God” begins. This is true. Over the past 20 years, the feeling has grown into the most significant expectation, permeating even solid political forecasts. This frightens some, but encourages others, because the death of the old is always the birth of the new. But the “death of God” is more a symptom than a cause of the turmoil of today’s world, and the solution to these problems lies beyond its 4000-year history...

Karen Armstrong

History of God

Preface

As a child, I had strong religious beliefs and a fairly weak faith in God. There is a difference between beliefs (where we accept certain statements on faith) and real faith (when we rely completely on them). Of course, I believed that God exists. I believed in the real presence of Christ in the sacrament, in the effectiveness of the sacraments, and in the eternal torment awaiting sinners. I believed that purgatory was a very real place. However, I cannot say that these beliefs in religious dogmas about the nature of a higher reality gave me a genuine sense of the grace of earthly existence. When I was a child, Catholicism was mostly a fearful creed. James Joyce described it accurately in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man; I also listened to my course of sermons about fiery hell. To tell the truth, the torments of hell looked much more convincing than God. The underworld was easily comprehended by the imagination, but God remained an unclear figure and was defined not so much by visual images as by speculative reasoning. At the age of eight, I had to memorize the answer to the question “Who is God?” from the catechism: “God is the Supreme Spirit, the one Self-existent and infinite in all perfections.” Of course, I didn’t understand the meaning of these words. I must admit that they still leave me indifferent: such a definition has always seemed to me too dry, pompous and arrogant. And while working on this book, I came to the conclusion that it was also wrong.

As I grew up, I realized that religion is not only about fear. I read the lives of saints, the works of metaphysical poets, the poems of Thomas Eliot and some of the works of mystics - from those who wrote more simply. The liturgy began to captivate me with its beauty. God still remained distant, but I felt that He could still be reached and that touching Him would instantly transform the entire universe. For this reason I joined one of the spiritual orders. After becoming a nun, I learned a lot more about faith. I immersed myself in apologetics, theological studies, and church history. I studied the history of monastic life and embarked on detailed discussions about the charter of our order, which we were all obliged to know by heart. Oddly enough, God did not play such a big role in all this. The main attention was paid to minor details, the particulars of faith. During prayer, I desperately forced myself to concentrate all my thoughts on meeting with God, but He either remained a stern taskmaster, vigilantly monitoring any violation of the rules, or - what was even more painful - slipped away altogether. The more I read about the mystical delights of the righteous, the more saddened I was by my own failures. I bitterly admitted to myself that even those rare religious experiences that I had could well have been the fruit of my own imagination, the result of a burning desire to experience them. Religious feeling is often an aesthetic response to the charm of liturgy and Gregorian chant. One way or another, nothing happened to me that came from outside. I have never felt those glimpses of God's presence that the mystics and prophets spoke about. Jesus Christ, about whom we spoke much more often than about God himself, seemed to be a purely historical figure, inseparable from the era of late antiquity. To make matters worse, I began to increasingly doubt certain church doctrines. How can one be sure, for example, that Jesus was God incarnate? What does this idea even mean? What about the doctrine of the Trinity? Is this complex - and extremely controversial - concept actually found in the New Testament? Perhaps, like many other theological constructs, the Trinity was simply invented by the clergy centuries after the execution of Jesus in Jerusalem?

Eventually, though not without regret, I withdrew from religious life, a step that immediately freed me from the burden of failure and feelings of inferiority. I felt my faith in God weakening. To tell the truth, He never left a significant mark on my life, although I tried with all my might to do so. And I felt neither guilt nor regret - God became too distant to seem something real. However, I retained my interest in religion itself. I have produced a number of television programs dealing with the early history of Christianity and religious experiences. As I studied the history of religion, I became increasingly convinced that my earlier fears were well founded. Doctrines that were accepted without reasoning in youth were indeed invented by people and perfected over many centuries. Science has clearly eliminated the need for a Creator, and Bible scholars have proven that Jesus never claimed divinity. During epileptic seizures, I had visions, but I knew that these were only symptoms of neuropathology; Perhaps the mystical delight of saints and prophets should also be attributed to the quirks of the psyche? God began to seem to me like some kind of insanity that the human race has long outgrown.

Despite the years I lived in the monastery, I do not consider my religious experiences to be anything unusual. My ideas about God were formed in early childhood, but later they could not get along with knowledge in other areas. I reconsidered my naive childhood beliefs in Santa Claus; I grew out of diapers and came to a more mature understanding of the complexity of human life. But my early confused ideas about God never changed. Yes, my religious upbringing was quite unusual, but many other people may find that their ideas about God were formed in infancy. Much water has passed under the bridge since then, we have abandoned simple-minded views - and with them the God of our childhood.

Nevertheless, my research in the field of the history of religion confirmed that man is a spiritual animal. There is every reason to believe that Homo sapiens is also Homo religiosus. People have believed in gods since they acquired human traits. Religions arose along with the first works of art. And this happened not simply because people wanted to appease powerful higher forces. Already in the most ancient beliefs, that sense of miracle and mystery is manifested, which still remains an integral part of human perception of our beautiful and terrible world. Like art, religion is an attempt to find the meaning of life, to reveal its values - despite the suffering to which the flesh is doomed. In the religious sphere, as in any other area of human activity, abuses occur, but we simply cannot seem to behave differently. Abuse is a natural universal human trait, and it is by no means limited to the eternal mundaneness of powerful kings and priests. Truly, modern secularized society is an unprecedented experiment that has no analogues in the history of mankind. And we still have to find out how it will turn out. It is also true that the liberal humanism of the West does not arise on its own - it needs to be taught, just as one is taught to understand painting or poetry. Humanism is also a religion, only without God, because not all religions have God. Our worldly ethical ideal is also based on certain concepts of the mind and soul and, like more traditional religions, provides the basis for the same belief in the highest meaning of human life.

When I began studying the history of ideal and experiential concepts of God in the three closely related religions of monotheism - Judaism, Christianity and Islam - I knew that God would turn out to be simply a projection of human needs and desires. I considered “Him” to be a reflection of the fears and aspirations of society at various stages of growth. It cannot be said that these assumptions were completely refuted, but some discoveries came as a complete surprise to me, and I regretted that I did not know all this thirty years ago, when my religious life was just beginning. I would have saved myself a lot of torment if I had heard back then from prominent representatives of each of the three religions that you should not wait for God to condescend to you - you should, on the contrary, consciously cultivate the feeling of His unchanging presence in your soul. If I had known wise rabbis, monks or Sufis then, they would have severely reprimanded me for suggesting that God is some kind of “external” reality. They would warn me that I cannot hope to perceive God as an objective fact amenable to ordinary rational thought. They would certainly say that in some very important sense God really is a product of the creative imagination, like the music and poetry that inspire me so much. And some of the most respectable monotheists would whisper to me in confidence that in fact there is no God, but at the same time “He” is the most important reality in the world.

This book is not dedicated to the history of the ineffable existence of God Himself, not subject to either time or change; This is the history of the human race's ideas about God - from Abraham to the present day. The human idea of God has its own history, because in different eras different peoples perceived Him in different ways. The concept of God held by one generation may be completely meaningless to another. The words “I believe in God” are devoid of objective content. Like any other statement, they are filled with meaning only in the context when uttered by a member of a particular society. Thus, behind the concept “God” there is not at all hidden some unchanging idea. On the contrary, it contains a wide range of meanings, some of which may completely negate each other and even turn out to be internally contradictory. Without such flexibility, the idea of God would never have occupied one of the main places in the history of human thought. And when some ideas about God lost their meaning or became outdated, they were simply quietly forgotten and replaced by new theologies. Fundamentalists, of course, will not agree with this, because fundamentalism itself is ahistorical and is based on the belief that Abraham, Moses and the ancient prophets perceived God exactly as modern people do. But if you take a closer look at our three religions, it becomes clear that they do not have an objective opinion about “God”: each generation creates an image of Him that corresponds to its historical tasks. By the way, the same applies to atheism, since the phrase “I don’t believe in God” also meant something different in different historical eras. The so-called “atheists” always deny certain specific ideas about the Divine. But who is this “God” that atheists today do not believe in - the God of the patriarchs, prophets, philosophers, mystics or deists of the eighteenth century? Judaists, Christians and Muslims in different historical eras worshiped all these gods, calling each one the God of the Bible or the Koran. We will see that in fact these gods were not at all similar to each other. Moreover, atheism often became a kind of transitional stage. There was a time when pagans called “atheists” the very Jews, Christians and Muslims who came to completely revolutionary ideas of the Divine and the Transcendent. Perhaps modern atheism is a similar denial of “God”, which has ceased to meet the needs of our era?

Karen Armstrong

Armstrong K. History of God MILLENNIAL SEARCH IN JUDAISM, CHRISTIANITY AND ISLAM

Translation by K. Semenov, ed. V. Trilis and M. Dobrovolsky

Karen Armstrong. The History of God

The 4000-years Quest of Judaism, Christianity and Islam

N.Y.: Ballantine Books, 1993

K.-M.: "Sofia", 2004

Preface

As a child, I had strong religious beliefs and a fairly weak faith in God. There is a difference between beliefs (where we accept certain statements on faith) and real faith (when we rely completely on them). Of course, I believed that God exists. I believed in the real presence of Christ in the sacrament, in the effectiveness of the sacraments, and in the eternal torment awaiting sinners. I believed that purgatory was a very real place. However, I cannot say that these beliefs in religious dogmas about the nature of a higher reality gave me a genuine sense of the grace of earthly existence. When I was a child, Catholicism was mostly a fearful creed. James Joyce described it accurately in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man; I also listened to my course of sermons about fiery hell. To tell the truth, the torments of hell looked much more convincing than God. The underworld was easily comprehended by the imagination, but God remained an unclear figure and was defined not so much by visual images as by speculative reasoning. At the age of eight, I had to memorize the answer to the question “Who is God?” from the catechism: “God is the Supreme Spirit, the one Self-existent and infinite in all perfections.” Of course, I didn’t understand the meaning of these words. I must admit that they still leave me indifferent: such a definition has always seemed to me too dry, pompous and arrogant. And while working on this book, I came to the conclusion that it was also wrong.

As I grew up, I realized that religion is not only about fear. I read the lives of saints, the works of metaphysical poets, the poems of Thomas Eliot and some of the works of mystics - from those who wrote more simply. The liturgy began to captivate me with its beauty. God still remained distant, but I felt that He could still be reached and that touching Him would instantly transform the entire universe. For this reason I joined one of the spiritual orders. After becoming a nun, I learned a lot more about faith. I immersed myself in apologetics, theological studies, and church history. I studied the history of monastic life and embarked on detailed discussions about the charter of our order, which we were all obliged to know by heart. Oddly enough, God did not play such a big role in all this. The main attention was paid to minor details, the particulars of faith. During prayer, I desperately forced myself to concentrate all my thoughts on meeting with God, but He either remained a stern taskmaster, vigilantly monitoring any violation of the rules, or - what was even more painful - slipped away altogether. The more I read about the mystical delights of the righteous, the more saddened I was by my own failures. I bitterly admitted to myself that even those rare religious experiences that I had could well have been the fruit of my own imagination, the result of a burning desire to experience them. Religious feeling is often an aesthetic response to the charm of liturgy and Gregorian chant. One way or another, nothing happened to me that came from outside. I have never felt those glimpses of God's presence that the mystics and prophets spoke about. Jesus Christ, about whom we spoke much more often than about God himself, seemed to be a purely historical figure, inseparable from the era of late antiquity. To make matters worse, I began to increasingly doubt certain church doctrines. How can one be sure, for example, that Jesus was God incarnate? What does this idea even mean? What about the doctrine of the Trinity? Is this complex - and extremely controversial - concept actually found in the New Testament? Perhaps, like many other theological constructs, the Trinity was simply invented by the clergy centuries after the execution of Jesus in Jerusalem?

Eventually, though not without regret, I withdrew from religious life, a step that immediately freed me from the burden of failure and feelings of inferiority. I felt my faith in God weakening. To tell the truth, He never left a significant mark on my life, although I tried with all my might to do so. And I felt neither guilt nor regret - God became too distant to seem something real. However, I retained my interest in religion itself. I have produced a number of television programs dealing with the early history of Christianity and religious experiences. As I studied the history of religion, I became increasingly convinced that my earlier fears were well founded. Doctrines that were accepted without reasoning in youth were indeed invented by people and perfected over many centuries. Science has clearly eliminated the need for a Creator, and Bible scholars have proven that Jesus never claimed divinity. During epileptic seizures, I had visions, but I knew that these were only symptoms of neuropathology; Perhaps the mystical delight of saints and prophets should also be attributed to the quirks of the psyche? God began to seem to me like some kind of insanity that the human race has long outgrown.

Despite the years I lived in the monastery, I do not consider my religious experiences to be anything unusual. My ideas about God were formed in early childhood, but later they could not get along with knowledge in other areas. I reconsidered my naive childhood beliefs in Santa Claus; I grew out of diapers and came to a more mature understanding of the complexity of human life. But my early confused ideas about God never changed. Yes, my religious upbringing was quite unusual, but many other people may find that their ideas about God were formed in infancy. Much water has passed under the bridge since then, we have abandoned simple-minded views - and with them the God of our childhood.

Nevertheless, my research in the field of the history of religion confirmed that man is a spiritual animal. There is every reason to believe that Homo sapiens is also Homo religiosus. People have believed in gods since they acquired human traits. Religions arose along with the first works of art. And this happened not simply because people wanted to appease powerful higher forces. Already in the most ancient beliefs, that sense of miracle and mystery is manifested, which still remains an integral part of human perception of our beautiful and terrible world. Like art, religion is an attempt to find the meaning of life, to reveal its values - despite the suffering to which the flesh is doomed. In the religious sphere, as in any other area of human activity, abuses occur, but we simply cannot seem to behave differently. Abuse is a natural universal human trait, and it is by no means limited to the eternal mundaneness of powerful kings and priests. Truly, modern secularized society is an unprecedented experiment that has no analogues in the history of mankind. And we still have to find out how it will turn out. It is also true that the liberal humanism of the West does not arise on its own - it needs to be taught, just as one is taught to understand painting or poetry. Humanism is also a religion, only without God, because not all religions have God. Our worldly ethical ideal is also based on certain concepts of the mind and soul and, like more traditional religions, provides the basis for the same belief in the highest meaning of human life.

When I began studying the history of ideal and experiential concepts of God in the three closely related religions of monotheism - Judaism, Christianity and Islam - I knew that God would turn out to be simply a projection of human needs and desires. I considered “Him” to be a reflection of the fears and aspirations of society at various stages of growth. It cannot be said that these assumptions were completely refuted, but some discoveries came as a complete surprise to me, and I regretted that I did not know all this thirty years ago, when my religious life was just beginning. I would have saved myself a lot of torment if I had heard back then from prominent representatives of each of the three religions that you should not wait for God to condescend to you - you should, on the contrary, consciously cultivate the feeling of His unchanging presence in your soul. If I had known wise rabbis, monks or Sufis then, they would have severely reprimanded me for suggesting that God is some kind of “external” reality. They would warn me that I cannot hope to perceive God as an objective fact amenable to ordinary rational thought. They would certainly say that in some very important sense God really is a product of the creative imagination, like the music and poetry that inspire me so much. And some of the most respectable monotheists would whisper to me in confidence that in fact there is no God, but at the same time “He” is the most important reality in the world.

This book is not dedicated to the history of the ineffable existence of God Himself, not subject to either time or change; This is the history of the human race's ideas about God - from Abraham to the present day. The human idea of God has its own history, because in different eras different peoples perceived Him in different ways. The concept of God held by one generation may be completely meaningless to another. The words “I believe in God” are devoid of objective content. Like any other statement, they are filled with meaning only in the context when uttered by a member of a particular society. Thus, behind the concept “God” there is not at all hidden some unchanging idea. On the contrary, it accommodates the widest...