C.P.Snow. Two cultures. Two cultures and the scientific revolution. Charles Percy Snow Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution in Brief

MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND SCIENCE

RUSSIAN FEDERATION

Federal Agency for Education

Kurgan State University

COURSE READER

“CONCEPTS OF MODERN NATURAL SCIENCE”

Part I

PHYSICS

Kurgan 2006

Reader on training course"Concepts of modern natural science." Part I. Physics / Comp. G.V., Bogomolova, L.F. Ostroukhova – Kurgan: Kurgan State Publishing House, 2006. – 148 p.

Published by decision of the educational and methodological council of Kurgan State University

Reviewers: Department of Philosophy and History of the T.S. Maltsev KSHA (Head of the Department of Candidate of Philosophy Sciences, Associate Professor L.Kh. Tsibaev); Candidate of Philosophical Sciences, Associate Professor, Head of the Department of Social and Humanitarian Disciplines of the Kurgan Institute of State and Municipal Service V.G. Tatarintsev.

The anthology presents fragments taken from the works of famous Western and domestic physicists and philosophers, the understanding of which will help students in preparing for seminar classes, tests and exams for the training course “Concepts of modern natural science”

Responsible editor: Candidate of Philosophy, Professor, Head of the Department of Philosophy I.N. Stepanova.

© Kurgansky

state

University, 2006.

TWO CULTURES: NATURAL SCIENCE

AND HUMANITARIAN

C.P.Snow. Two cultures

About three years ago I touched upon in print an issue that had been causing me a feeling of concern for a long time. I encountered this problem due to some features of my biography... It's all about the unusualness of my life experience. I am a scientist by education and a writer by vocation. That's all. But I'm not going to tell my life story now. It is important for me to say only one thing: I had the rare happiness of observing up close one of the most amazing creative breakthroughs that the history of physics has known...

It so happened that for thirty years I maintained contact with scientists not only out of curiosity, but also because it was part of my daily duties. And during these same thirty years I tried to imagine the general contours of the yet unwritten books that eventually made me a writer.

Very often - not figuratively, but literally - I spent the daytime hours with scientists and the evenings with my literary friends. It goes without saying that I had close friends among both scientists and writers. Thanks to the fact that I was in close contact with both, and, probably, to an even greater extent due to the fact that I was constantly moving from one to the other, I began to be interested in the problem that I called for myself “two cultures” even before how I tried to put it on paper. This name arose from the feeling that I was constantly in contact with two different groups, quite comparable in intelligence, belonging to the same race, not very different in social origin, having approximately the same means of livelihood and at the same time almost lost the ability to communicate with each other, living with such different interests, in such a dissimilar psychological and moral atmosphere, that it seems easier to cross the ocean...

It seems to me that the spiritual world of the Western intelligentsia is becoming more and more clearly polarized, more and more clearly splitting into two opposite parts. Speaking about the spiritual world, I finally include our practical activities, because I am one of those who are convinced that, essentially, these aspects of life are inseparable. And now about two opposite parts. At one pole - who accidentally, taking advantage of the fact that no one noticed this in time, began to call themselves simply intellectuals, as if no other intelligentsia existed at all. I remember how one day in the 1930s Hardy said to me in surprise: “Have you noticed how the words “intelligent people” are now being used? Their meaning has changed so much that Rutherford, Eddington, Dirac, Adrian and I - we all no longer seem to fit this new definition! This seems rather strange to me, don’t you?”

So, at one pole - artistic intelligentsia, on another - scientists, and as the most prominent representatives of this group - physicists. They are separated by a wall of misunderstanding, and sometimes - especially among young people - even antipathy and enmity. But the main thing, of course, is misunderstanding. Both groups have a strange, twisted view of each other. They have such different attitudes to the same things that they cannot find a common language even in terms of emotions...

At one pole is a culture created by science. It really exists as a specific culture, not only in an intellectual sense, but also in an anthropological sense. This means that those involved do not need to fully understand each other, which happens quite often. Biologists, for example, quite often do not have the slightest idea about modern physics. But biologists and physicists are united by a common attitude towards the world; they have the same style and the same norms of behavior, similar approaches to problems and related starting positions. This community is amazingly broad and deep. She makes her way in defiance of all other internal connections: religious, political, class.

I think that, upon statistical testing, there will be slightly more non-believers among scientists than among other groups of the intelligentsia, and in the younger generation there are apparently even more of them, although there are not so few believing scientists either. The same statistics show that the majority of scientists adhere to left-wing views in politics, and their number among young people is obviously increasing, although again there are many conservative scientists. Among scientists in England and, probably, the USA, there are significantly more people from poor families than among other groups of intellectuals. However, none of these circumstances has a particularly serious impact on the general structure of scientists' thinking and on their behavior. By the nature of their work and by the general structure of their spiritual life, they are much closer to each other than to other intellectuals who adhere to the same religious and political views or come from the same environment. If I were to venture into shorthand, I would say that they are all united by the future that they carry in their blood. Even without thinking about the future, they equally feel their responsibility to it. This is what is called general culture.

At the other pole, the attitude to life is much more diverse. It is quite obvious that if one wants to make a journey into the world of the intelligentsia, going from physicists to writers, one will encounter many different opinions and feelings. But I think that the pole of absolute misunderstanding of science cannot influence the entire sphere of its attraction. Absolute misunderstanding, which is much more widespread than we think - due to habit we simply do not notice it - gives a taste of unscientificness to the entire “traditional” culture, and often - more often than we think - this unscientificness barely rests on the verge of anti-science...

The polarization of culture is a clear loss for all of us. For us as a people, for our modern society. This is a practical, moral and creative loss, and I repeat: it would be vain to believe that these three points can be completely separated from one another. However, now I want to focus on moral losses.

Scientists and the artistic intelligentsia have ceased to understand each other to such an extent that it has become a ingrained anecdote. In England there are about 50 thousand scientists in the field of exact and natural sciences and about 80 thousand specialists (mainly engineers) engaged in the applications of science. During World War II and the post-war years, my colleagues and I managed to interview 30-40 thousand of both, that is, approximately 25%. This number is large enough to suggest a pattern, although most of those we interviewed were under forty years of age. We have some idea of what they are reading and thinking about. I admit that with all my love and respect for these people, I was somewhat depressed. We were completely unaware that their ties to traditional culture had weakened so much that they were reduced to polite nods...

They live by their full-blooded, well-defined and constantly developing culture. It is distinguished by many theoretical positions, usually much clearer and almost always much better substantiated than the theoretical positions of writers. And even when scientists, without thinking, use words differently from writers, they always give them the same meaning; if, for example, they use the words “subjective”, “objective”, “philosophy”, “progressive”, then they know perfectly well what they mean, although they often mean something completely different from everyone else.

Let's not forget that we are talking about highly intelligent people. In many ways, their strict culture is admirable. Art occupies a very modest place in this culture, albeit with one, but very important exception - music. Exchanges of opinions, intense discussions, long-playing records, color photography: a little for the ears, a little for the eyes. Very few books...

And almost nothing from those books that constitute the daily food of writers: almost no psychological and historical novels, poems, plays. Not because they are not interested in psychological, moral and social problems. Scientists, of course, come into contact with social problems more often than many writers and artists. In moral terms, they, in general, constitute the healthiest group of intellectuals, because the idea of justice is embedded in science itself, and almost all scientists independently develop their views on various issues of morality and morality. Scientists are interested in psychology to the same extent as most intellectuals, although sometimes it seems to me that their interest in this area appears relatively late. So it's obviously not a matter of lack of interest. Much of the problem is that the literature associated with our traditional culture is considered "irrelevant" by scholars. Of course, they are sadly mistaken. Because of this they suffer creative thinking. They are robbing themselves.

And the other side? She also loses a lot. And perhaps its losses are even greater because its representatives are more vain. They still pretend that traditional culture is all culture, as if the status quo doesn't really exist. It’s as if trying to understand the current situation is of no interest to her, either in itself or from the point of view of the consequences to which this situation can lead. As if the modern scientific model of the physical world, in its intellectual depth, complexity and harmony, is not the most beautiful and amazing creation created by the collective efforts of the human mind! But most of the artistic intelligentsia do not have the slightest idea about this creation. And she can’t have it, even if she wanted to. It seems that as a result of a huge number of sequential experiments, a whole group of people who did not perceive certain sounds was eliminated. The only difference is that this partial deafness is not a congenital defect, but the result of training, or rather, lack of training. As for the semi-deaf themselves, they simply do not understand what they were deprived of. When they hear about some discovery made by people who have never read the great works of English literature, they chuckle sympathetically. To them, these people are simply ignorant specialists whom they discount. Meanwhile, their own ignorance and the narrowness of their specialization are no less terrible. Many times I have been in the company of people who, according to the norms of traditional culture, are considered highly educated. Usually they are very passionately indignant at the literary illiteracy of scientists. One day I couldn’t resist and asked which of them could explain what the second law of thermodynamics is. The answer was silence or refusal. But asking this question to a scientist means about the same as asking a writer: “Have you read Shakespeare?”

Now I am convinced that if I had been interested in simpler things, for example, what mass is or what acceleration is, that is, I would have sunk to that level of scientific difficulty at which in the world of the artistic intelligentsia they ask: “Can you read?” then no more than one in ten highly cultured people would understand that we speak the same language. It turns out that the majestic edifice of modern physics is rising upward, and for most of the discerning people of the Western world it is as incomprehensible as it was for their Neolithic ancestors...

Snow Ch. Two cultures. – M., 1973.

W. Heisenberg

Object of study.

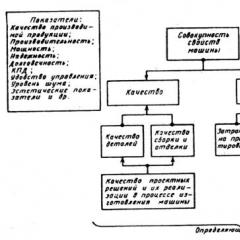

To date, two extensive and relatively independent areas of knowledge have formed, which differ in the object of study:

1. Natural science, the object of study of which was all forms of living and inanimate nature, including the biological aspects of human life;

2. Humanities and social sciences, the objects of study of which are human consciousness, creativity, social processes and their development, as well as ideal systems created by man (languages, law, religion, etc.).

As a result of the differences in the objects of knowledge and the relatively independent evolution, the natural and social sciences have developed their own methods and reached different levels of development. Contradictions arise between them due to differences in traditions, goals, methods, discrepancies in assessments of the same achievements of scientific and technological progress and trends in the development of society. The combination of these contradictions is sometimes called the problem of two cultures.

Scientific method in natural science:

1. the desire for clarity and unambiguity of concepts;

2. empirical (observational and experimental) basis of scientific knowledge;

3. instrumental methods obtaining information about the natural phenomena being studied;

4. the desire for quantitative characteristics of phenomena and, accordingly, for mathematical methods of information processing; widespread use of mathematical modeling methods;

5. logical (rational) basis and well-developed methodology for constructing theories;

6. reductionism - a way to explain complex phenomena by using ideas about simpler ones;

7. the idea of relativity, the fundamental incompleteness and inconclusiveness of scientific knowledge, as well as the continuity of theories;

8. the desire for conceptual unity of the theoretical description of nature.

Humanitarian scientific method

Humanitarian knowledge, especially art, is characterized by:

1. a holistic approach to the phenomena under consideration (synthesis) - the antipode of reductionism;

2. the forcedly approximate, not quantitative, but qualitative nature of information about the phenomena being studied, the difficulty of formalization, i.e. an accurate mathematical description (a kind of payment for a holistic approach);

3. interpretation - the personal (emotional) position of the researcher in relation to the phenomenon being studied, ethical and aesthetic assessments of the phenomena based on the moral principles of the researchers, as well as their political priorities, which in some cases can negate the significance of the research;

4. special meaning of intuitive, i.e. illogical approach to the study of phenomena.

The problem of two cultures

- In May 1959, at the University of Cambridge (England), the famous English scientist Charles Percy Snow gave a lecture “Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution.”

- Between the traditional and humanitarian culture of Europe and the new so-called. scientific culture derived from the scientific and technological process of the 20th century.

In our country this is reflected in the confrontation between physicists and lyricists (B. Slutsky’s poem “Physicists and Lyricists” 1959).

Convergence of natural science and humanities.

- Positive trends towards the rapprochement of two cultures, due to the need to solve complex problems of science, as well as global problems modern civilization.

- The penetration of natural scientific methods into the humanities and the penetration of a holistic worldview into natural science.

- Culture is a manifestation of creativity, creativity, regardless of the area in which this creativity is carried out; therefore, the convergence of natural and humanitarian culture is objectively natural.

The concept of culture itself is very broad: it manifests itself in concrete transformative human activity and in the subjective abilities of people, in creativity, in legal, religious, and moral norms. Culture breaks down into two poles: material and spiritual culture, or natural science and humanitarian culture. The split between them occurred not only on the pages, but also in society.

At the end of the 20th century, the world comes to the separation of the rational, natural and spiritual, humanitarian, and ethics falls into the sphere of the irrational. The harmony of the unity of two cultures begins to be disrupted even earlier and there are many reasons for this: narrow professionalization associated with deepening knowledge, with the formation of a consumer society, with the emergence of scientific discoveries powerful weapons And environmental problems. An important role is played by ideological interpretations of some scientific theories, among which the most striking example is Darwin’s theory of the origin of man and the concept of the struggle for existence.

The split between cultures creates the need for cultural integration, or convergence. An example of knowledge integration is the science of cybernetics - the science of general laws of control in nature and in human society.

In the Soviet Union - the problem of physicists and lyricists, there was no such fierce antagonism as in the West, but disputes about the relationship between technology and nature, about the prospects for the development of cybernetics, about the moral side of experiments on animals and humans, the general thing is that science is contrasted with spirituality.

The problem of two cultures was first formulated by the English writer and physicist Charles Snow in 1959. In the Reed Lecture delivered at Cambridge, he noted that in society there is an increasingly clear split between two social groups, between representatives of the natural sciences and social and humanitarian fields. People of different professions often interact with each other, but there is a gap between them, there are no common interests and topics for conversation. Moreover, representatives of the two cultures treat each other arrogantly and disrespectfully towards each other’s subjects of study. Such an abyss, according to Snow, leads to the destruction of humanity. Reed's lecture led to educational reform: humanities majors began to study the basics of natural science and vice versa.

1. What two cultures has the spiritual world of modern man split into?

2. Why don’t writers, artists and scientists understand each other?

3. What can art give to the imaginative thinking of a scientist?

5. What can acquaintance with industrial technology give a scientist?

It seems to me that the spiritual world of the Western intelligentsia is becoming more and more clearly polarized, more and more clearly splitting into two opposite parts. Speaking about the spiritual world, I largely include our practical activities in it, since I am one of those who are convinced that, in essence, these aspects of life are inseparable. And now about two opposite parts. At one extreme is the artistic intelligentsia, which by chance, taking advantage of the fact that no one noticed this in time, began to call itself simply the intelligentsia, as if no other intelligentsia existed at all. I remember how one day in the thirties Hardy said to me with surprise: “Have you noticed how the words “intelligent people” are now being used? Their meaning has changed so much that Rutherford, Eddington, Dirac, Adrian and I - we all no longer seem to fit this new definition! This seems rather strange to me, don’t you?”

So, at one pole are the artistic intelligentsia, at the other are scientists, and as the most prominent representatives of this group are physicists. They are separated by a wall of misunderstanding, and sometimes - especially among young people - even antipathy and enmity. But the main thing, of course, is misunderstanding. Both groups have a strange, twisted view of each other. They have such different attitudes to the same things that they cannot find a common language even in terms of emotions. Non-scientists tend to think of scientists as arrogant braggarts. They hear Mr. T. S. Eliot—there could hardly be a more emphatic figure to illustrate this point—talk of his attempts to revive the verse drama, and say that, although not many share his hopes, his like-minded people would be glad if they will be able to pave the way for a new Kid or a new Green. This is the muted manner of expression that is accepted among the artistic intelligentsia; such is the restrained voice of their culture. And suddenly the incomparably louder voice of another typical figure reaches them. “This is the heroic era of science! - proclaims Rutherford. “The Elizabethan age has come!” Many of us have repeatedly heard similar statements and not so few others, in comparison with which those just cited sound very modest, and none of us doubted who exactly Rutherford predicted for the role of Shakespeare. But unlike us, writers and artists fail to understand that Rutherford is absolutely right; here both their imagination and their reason are meaningless.

Compare the words that sound least like scientific prophecy: “This is how the world will end. Not an explosion, but a sob.” Compare them with Rutherford's famous witticism. “Lucky Rutherford, you are always on the wave!” - they told him once. “That's true,” he replied, “but I made the wave after all, didn't I?”

There is a strong opinion among the artistic intelligentsia that scientists do not imagine real life and therefore they are characterized by superficial optimism. Scientists, for their part, believe that the artistic intelligentsia is devoid of the gift of providence, that it shows a strange indifference to the fate of humanity, that everything related to reason is alien to it, that it tries to limit art and thinking only to today's concerns, and so on.

Any person who has the most modest experience prosecutor, could add many other unspoken accusations to this list. Some of them are not without foundation, and this applies equally to both groups of intelligentsia. But all these arguments are fruitless. Most of the accusations were born from a distorted understanding of reality, which is always fraught with many dangers. Therefore, now I would like to touch only on the two most serious of the mutual reproaches, one on each side.

First of all, about the “superficial optimism” characteristic of scientists. This accusation is made so often that it has become commonplace. Even the most insightful writers and artists support it. It arose due to the fact that the personal life experience of each of us is taken as social, and the conditions of existence of an individual are perceived as a general law. Most scientists I know well, as well as most of my non-scientist friends, understand perfectly well that the fate of each of us is tragic. We're all alone. Love, strong affections, creative impulses sometimes allow us to forget about loneliness, but these triumphs are only bright oases created by our own hands, and the end of the path always ends in darkness: everyone faces death alone. Some scientists I know find solace in religion. Maybe they feel the tragedy of life less acutely. I don't know. But most people, endowed with deep feelings, no matter how cheerful and happy they are - the most cheerful and happy even more so than others - perceive this tragedy as one of the inalienable conditions of life. This applies equally to the people of science I know well, and to all people in general.

But almost all scientists - and here a ray of hope appears - see no reason to consider the existence of humanity tragic simply because the life of each individual ends in death. Yes, we are alone, and everyone faces death alone. So what? This is our fate, and we cannot change it. But our lives depend on many circumstances that have nothing to do with fate, and we must resist them if we want to remain human.

Most members of the human race suffer from starvation and die prematurely. These are the social conditions of life. When a person is faced with the problem of loneliness, he sometimes falls into a kind of moral trap: he plunges contentedly into his personal tragedy and stops worrying about those who cannot satisfy their hunger.

Scientists usually fall into this trap less often than others. They are characterized by an impatient desire to find some way out and usually they believe that this is possible until they are convinced of the opposite. This is their true optimism - the optimism that we all desperately need.

The same will to goodness, the same persistent desire to fight alongside one’s blood brothers, naturally makes scientists treat with contempt the intelligentsia who occupy different social positions. Moreover, in some cases these positions really deserve contempt, although such a situation is usually temporary, and therefore it is not so typical.

I remember being interrogated with passion by one eminent scientist: “Why do most writers adhere to views that would certainly have been considered backward and out of fashion even in the time of the Plantagenets? Are the outstanding writers of the twentieth century an exception to this rule? Yeats, Pound, Lewis - nine out of ten among those who determined the general sound of literature in our time - have they not shown themselves to be political fools, and even more so - political traitors? Didn’t their creativity bring Auschwitz closer?”

I thought then and I think now that the correct answer is not to deny the obvious. It is useless to say that, according to friends whose opinions I trust, Yeats was a man of exceptional generosity and also a great poet. It is useless to deny facts that are fundamentally true. The honest answer to this question is to admit that there is indeed some connection between some works of art of the early twentieth century and the most monstrous manifestations of antisocial feelings, and that writers noticed this connection with a belated delay that deserves all the blame. This circumstance is one of the reasons that prompted some of us to turn away from art and look for new paths for ourselves.

However, although for a whole generation of people the general sound of literature was determined primarily by the work of writers like Yeats and Pound, now the situation is, if not completely, then significantly different. Literature changes much more slowly than science. And therefore, periods when development takes the wrong path are longer in literature. But, while remaining conscientious, scientists cannot judge writers only on the basis of facts relating to the years 1914 - 1950.

These are the two sources of misunderstanding between the two cultures. I must say, since I started talking about two cultures, that this term itself has caused a number of criticisms. Most of my friends from the world of science and art find it to some extent successful. But people associated with purely practical activities strongly disagree with this. They see this division as an oversimplification and believe that if we resort to such terminology, then we must talk about at least three cultures. They claim that they largely share the views of scientists, although they themselves are not one of them; modern works of fiction tell them as little as they tell scientists (and would probably say even less if they knew them better). J. H. Plum, Alan Bullock and some of my American sociologist friends strongly object to being forced to be considered helpers and those who create an atmosphere of social hopelessness, and being locked in the same cage with people with whom they would not want to be. together not only alive, but also dead.

I tend to respect these arguments. Number two is a dangerous number. Attempts to divide anything into two parts, naturally, should inspire the most serious fears. At one time I thought about making some additions, but then I abandoned this idea. I wanted to find something more than an expressive metaphor, but much less than a precise diagram of cultural life. For these purposes, the concept of “two cultures” fits perfectly; any further clarification would do more harm than good.

At one pole is a culture created by science. It really exists as a specific culture, not only in an intellectual sense, but also in an anthropological sense. This means that those involved do not need to fully understand each other, which happens quite often. Biologists, for example, quite often do not have the slightest idea about modern physics. But biologists and physicists are united by a common attitude towards the world; they have the same style and the same norms of behavior, similar approaches to problems and related starting positions. This community is amazingly broad and deep. She makes her way in defiance of all other internal connections: religious, political, class.

I think that, upon statistical testing, there will be slightly more non-believers among scientists than among other groups of the intelligentsia, and in the younger generation there are apparently even more of them, although there are not so few believing scientists either. The same statistics show that the majority of scientists adhere to left-wing views in politics, and their number among young people is obviously increasing, although again there are many conservative scientists. Among scientists in England and, probably, the USA, there are significantly more people from poor families than among other groups of intellectuals. However, none of these circumstances has a particularly serious impact on the general structure of scientists' thinking and on their behavior. By the nature of their work and by the general structure of their spiritual life, they are much closer to each other than to other intellectuals who hold the same religious and political views or come from the same environment. If I were to venture into shorthand, I would say that they are all united by the future that they carry in their blood. Even without thinking about the future, they equally feel their responsibility to it. This is what is called common culture.

At the other pole, the attitude to life is much more diverse. It is quite obvious that if one wants to make a journey into the world of the intelligentsia, going from physicists to writers, one will encounter many different opinions and feelings. But I think that the pole of absolute misunderstanding of science cannot but influence the entire sphere of its attraction. Absolute misunderstanding, widespread much more widely than we think - due to habit we simply do not notice it - gives a taste of unscientificness to the entire “traditional” culture, and often - more often than we think - this unscientificness almost crosses the brink of anti-science. The aspirations of one pole give rise to their antipodes at the other. If scientists carry the future in their blood, then representatives of “traditional” culture strive to ensure that the future does not exist at all. The Western world is governed by traditional culture, and the intrusion of science has only shaken its dominance to a negligible extent.

The polarization of culture is a clear loss for all of us. For us as a people and for our modern society. This is a practical, moral and creative loss, and I repeat: it would be vain to believe that these three points can be completely separated from one another. However, now I want to focus on moral losses.

Scientists and the artistic intelligentsia have ceased to understand each other to such an extent that it has become a ingrained anecdote. In England there are about 50 thousand scientists in the field of exact and natural sciences and about 80 thousand specialists (mainly engineers) engaged in the applications of science. During the Second World War and in the post-war years, my colleagues and I managed to interview 30 - 40 thousand of both, that is, approximately 25%. This number is large enough to suggest a pattern, although most of those we interviewed were under forty years of age. We have some idea of what they are reading and thinking about. I admit that with all my love and respect for these people, I was somewhat depressed. We were completely unaware that their ties to traditional culture had become so weakened that they were reduced to polite nods.

It goes without saying that there have always been outstanding scientists, possessed of remarkable energy and interested in a wide variety of things; they still exist, and many of them have read everything that is usually talked about in literary circles. But this is an exception. Most, when we tried to find out what books they had read, modestly admitted: “You see, I tried to read Dickens...” And this was said in such a tone as if we were talking about Rainer Maria Rilke, that is, about an extremely complex, accessible writer understood only by a handful of initiates and hardly worthy of real approval. They really treat Dickens like they treat Rilke. One of the most surprising results of this survey was perhaps the discovery that Dickens's work has become an example of obscure literature.

When they read Dickens or any other writer we value, they only nod politely to traditional culture. They live by their full-blooded, well-defined and constantly developing culture. It is distinguished by many theoretical positions, usually much clearer and almost always much better substantiated than the theoretical positions of writers. And even when scientists do not hesitate to use words differently from writers, they always give them the same meaning; if, for example, they use the words “subjective”, “objective”, “philosophy”, “progressive”, then they know perfectly well what they mean, although they often mean something completely different from everyone else.

Let's not forget that we are talking about highly intelligent people. In many ways, their strict culture is admirable. Art occupies a very modest place in this culture, albeit with one, but very important exception - music. Exchanges of opinions, intense discussions, long-playing records, color photography: a little for the ears, a little for the eyes. Very few books, although probably not many, have gone as far as a certain gentleman, who is obviously on a lower rung of the scientific ladder than the scientists I have just spoken of. This gentleman, when asked what books he reads, answered with unshakable self-confidence: “Books? I prefer to use them as tools.” It is difficult to understand what tools he “uses” them as. Maybe as a hammer? Or shovels?

So, there are still very few books. And almost nothing from those books that constitute the daily food of writers: almost no psychological and historical novels, poems, plays. Not because they are not interested in psychological, moral and social problems. Scientists, of course, come into contact with social problems more often than many writers and artists. In moral terms, they, in general, constitute the healthiest group of intellectuals, because the idea of justice is embedded in science itself and almost all scientists independently develop their views on various issues of morality and morality. Scientists are interested in psychology to the same extent as most intellectuals, although sometimes it seems to me that their interest in this area appears relatively late. So it's obviously not a matter of lack of interest. Much of the problem is that the literature associated with our traditional culture is considered “irrelevant” by scientists. Of course, they are sadly mistaken. Because of this, their imaginative thinking suffers. They are robbing themselves.

And the other side? She also loses a lot. And perhaps its losses are even greater because its representatives are more vain. They still pretend that traditional culture is all culture, as if the status quo doesn't really exist. It’s as if trying to understand the current situation is of no interest to her, either in itself or from the point of view of the consequences to which this situation can lead. As if the modern scientific model of the physical world, in its intellectual depth, complexity and harmony, is not the most beautiful and amazing creation created by the collective efforts of the human mind! But most of the artistic intelligentsia do not have the slightest idea about this creation. And she can’t have it, even if she wanted to. It seems that as a result of a huge number of sequential experiments, a whole group of people who did not perceive certain sounds was eliminated. The only difference is that this partial deafness is not a congenital defect, but the result of training - or rather, lack of training. As for the semi-deaf themselves, they simply do not understand what they are missing. When they hear about some discovery made by people who have never read the great works of English literature, they chuckle sympathetically. To them, these people are simply ignorant specialists whom they discount. Meanwhile, their own ignorance and the narrowness of their specialization are no less terrible. Many times I have been in the company of people who, according to the norms of traditional culture, are considered highly educated. Usually they are very passionately indignant at the literary illiteracy of scientists. One day I couldn’t resist and asked which of them could explain what the second law of thermodynamics is. The answer was silence or refusal. But asking this question to a scientist means about the same as asking a writer: “Have you read Shakespeare?”

Now I am convinced that if I had been interested in simpler things, for example, what mass is or what acceleration is, that is, I would have sunk to that level of scientific difficulty at which in the world of the artistic intelligentsia they ask: “Can you read?” then no more than one in ten highly cultured people would understand that we speak the same language. It turns out that the magnificent edifice of modern physics is rising upward, and for most of the insightful people of the Western world it is as incomprehensible as it was for their Neolithic ancestors.

Now I would like to ask one more question from among those that my friends - writers and artists consider the most tactless. At the University of Cambridge, professors of science, science and humanities meet each other for lunch every day. About two years ago, one of the most remarkable discoveries in the history of science was made. I don't mean satellite. The launch of Sputnik is an event that deserves admiration for completely different reasons: it was proof of the triumph of organization and the limitless possibilities of applying modern science. But now I'm talking about Yang and Lee's discovery. The research they carried out is remarkable for its amazing perfection and originality, but its results are so terrifying that you involuntarily forget about the beauty of thinking. Their work has forced us to reconsider some of the fundamental laws of the physical world. Intuition, common sense - everything was turned upside down. The result they obtained is usually formulated as parity non-conservation. If there were living connections between the two cultures, this discovery would be talked about at every professor's table in Cambridge. Did they actually say that? I was not in Cambridge at the time, and this was precisely the question I wanted to ask.

It seems that there is no basis at all for the unification of the two cultures. I'm not going to waste my time talking about how sad this is. Moreover, in fact, this is not only sad, but also tragic. What this means practically, I will say a little below. For our mental and creative activity, this means that the richest opportunities are wasted. A clash of two disciplines, two systems, two cultures, two galaxies - if you are not afraid to go that far! – cannot help but strike a creative spark. As can be seen from the history of the intellectual development of mankind, such sparks have indeed always flared up where habitual connections have been severed. For now, we continue to pin our creative hopes primarily on these flares. But today our hopes are unfortunately up in the air because people belonging to two cultures have lost the ability to communicate with each other. It is truly surprising how superficial the influence of twentieth-century science on modern art has been. From time to time, one comes across poems in which poets deliberately use scientific terms, and usually incorrectly. At one time, the word “refraction” came into fashion in poetry, acquiring an absolutely fantastic meaning. Then the expression “polarized light” appeared, from the context in which it is used, one can understand that writers believe that this is some kind of especially beautiful light. It is absolutely clear that in this form science can hardly bring any benefit to art. It must be accepted by art as an integral part of our entire intellectual experience and used as freely as any other material. I have already said that the demarcation of culture is not a specifically English phenomenon - it is characteristic of the entire Western world. But the point, obviously, is that in England it manifested itself especially sharply. This happened for two reasons. First, because of the fanatical belief in specialization of learning, which has gone far further in England than in any other country, Western or Eastern. Secondly, because of the characteristic tendency in England to create unchanging forms for all manifestations of social life. As economic inequality is leveled out, this trend does not weaken, but intensifies, which is especially noticeable in the English education system. In practice, this means that as soon as something like a division of culture occurs, all social forces contribute not to eliminating this phenomenon, but to consolidating it. The split in culture became an obvious and alarming reality 60 years ago. But in those days, the Prime Minister of England, Lord Salisbury, had a scientific laboratory in Hatfield, and Arthur Balfour was interested in natural sciences much more serious than just an amateur. John Andersen, before entering public service, was engaged in research in the field of inorganic chemistry in Leipzig, being simultaneously interested in so many scientific disciplines that now it seems simply unthinkable. Nothing like it is to be found in the highest spheres of England these days; Now even the very possibility of such an interweaving of interests seems absolutely fantastic.

Attempts to build a bridge between scientists and non-scientists in England look now - especially among young people - much more hopeless than thirty years ago. At that time, the two cultures, which had long since lost the ability to communicate, still exchanged polite smiles, despite the chasm that separated them. Now politeness is forgotten, and we exchange only barbs. Moreover, young scientists feel involved in the blossoming that science is now experiencing, and the artistic intelligentsia suffers from the fact that literature and art have lost their former importance. Aspiring scientists are also confident - let's be rude - that they will get a well-paid job, even without particularly high qualifications, while their comrades specializing in English literature or history will be happy to receive 50% of their salary. Not a single young scientist of the most modest abilities suffers from the consciousness of his own uselessness or from the meaninglessness of his work, like the hero of “Lucky Jim”, and in fact, in essence, the “angry” of Amis and his associates is to some extent caused by the fact that artistic the intelligentsia is deprived of the opportunity to fully use its powers. There is only one way out of this situation: first of all, change the existing education system.

TWO CULTURES

AND

SCIENTIFIC REVOLUTION

Charles Percy Snow

Reproduced from:

Ch.P. Snow, Portraits and reflections, M., Ed. "Progress", 1985, pp. 195-226

1. Two cultures

About three years ago I touched upon in print a problem that had been causing me a feeling of concern for a long time*. I encountered this problem due to some features of my biography. There were no other reasons that made me think in this particular direction - a certain coincidence of circumstances, and nothing more. Any other person, if his life had turned out the same way as mine, would have seen approximately the same thing as I did, and probably would have come to almost the same conclusions.

It's all about the unusualness of my life experience. I am a scientist by education and a writer by vocation. That's all. Besides, I was lucky, if you like: I was born into a poor family. But I'm not going to tell my life story now. It is important for me to say only one thing: I got into Cambridge and got the opportunity to study research work at a time when the University of Cambridge was experiencing its scientific heyday. I had the rare fortune of observing up close one of the most amazing creative explosions that the history of physics has known. And the vicissitudes of wartime - including a meeting with W.L. Bragg in the Kettering station cafeteria on a bitterly cold morning in 1939, a meeting that largely shaped my business life - helped me, nay, forced me, to maintain this closeness to this day. It so happened that for thirty years I maintained contact with scientists not only out of curiosity, but also because it was part of my daily duties. And during these same thirty years I tried to imagine the general contours of the yet unwritten books that eventually made me a writer.

* "The Two Cultures". - New Statesman, October 6, 1956. - Here and below in blue are the author's notes.

Very often - not figuratively, but literally - I spent the daytime hours with scientists, and the evenings with my literary friends. It goes without saying that I had close friends among both scientists and writers. Thanks to the fact that I was in close contact with both, and, probably, to an even greater extent due to the fact that I was constantly moving from one to the other, I began to be interested in the problem that I called for myself “two cultures” even before how I tried to put it on paper. This name arose from the feeling that I was constantly in contact with two different groups, quite comparable in intelligence, belonging to the same race, not very different in social origin, having approximately the same means of livelihood and at the same time almost lost the ability to communicate with each other, living with such different interests, in such a dissimilar psychological and moral atmosphere, that it seems easier to cross the ocean than to travel from Burlington House or South Kensington to Chelsea.

Transcript

1 Charles Snow Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution Very often, not figuratively but literally, I spent my afternoons with scientists and my evenings with my literary friends. It goes without saying that I had close friends among both scientists and writers. Thanks to the fact that I was in close contact with both, and, probably, to an even greater extent due to the fact that I was constantly moving from one to the other, I began to be interested in the problem that I called for myself “two cultures” even before how I tried to put it on paper. This name arose from the feeling that I was constantly in contact with two different groups, quite comparable in intelligence, belonging to the same race, not very different in social origin, having approximately the same means of livelihood and at the same time almost lost the ability to communicate with each other, living with such different interests, in such dissimilar psychological and moral atmospheres, that it seems easier to cross the ocean than to travel from Burlington House or South Kensington to Chelsea 1. This is actually more difficult, since, having overcome several thousand miles of Atlantic waters, you will find yourself in Greenwich Village, where they speak the same language as in Chelsea; but Greenwich Village and Chelsea do not understand MIT 2 to such an extent that one would think that scientists do not speak any language except Tibetan. Because this is not only an English problem. Some features of the English education system and public life make it especially acute in England, certain features of the social structure partially smooth it out, but in one form or another it exists for the entire Western world. Having expressed this thought, I want to immediately warn that I mean something quite serious, and not a funny anecdote about how one of the wonderful Oxford professors, a lively and sociable man, attended a dinner in Cambridge. When I heard this story, A.L. appeared as the main character. Smith, and it seems to date back to 1890. The dinner took place, in all likelihood, at St. Johnson's College or Trinity College. Smith sat to the right of the rector, or perhaps the deputy rector. He was a man who loved to talk. True, this time the expression on the faces of his dining companions was not very conducive to verbosity. He tried to strike up the usual casual conversation with his counterpart, the usual for Oxford residents. In response, an indistinct hum was heard. He tried to engage the neighbor on the right into the conversation - and again heard the same moo. To his great amazement, the two men looked at each other and one of them asked, “You don’t know what he’s talking about?” “I don’t have the slightest idea,” replied the other. Even Smith couldn't stand it. Fortunately, the rector, fulfilling his duties as a peacemaker, immediately restored his good spirits. “Oh, they’re mathematicians!” he said. “We never talk to them...” But I don’t mean this anecdote, but something completely serious. It seems to me that the spiritual world of the Western intelligentsia is becoming more and more clearly polarized, more and more clearly splitting into two opposite parts. When speaking about the spiritual world, I largely include our practical activities in it, since I am one of those who 1 Burlington House is an art salon in London, which hosts art exhibitions of the Royal Academy of Arts; Chelsea is an area of London that is home to many young artists. The British Museum's natural science department is located in South Kensington. 2 MIT - Massachusetts Institute of Technology, located in the USA in the city of Cambridge.

2 is convinced that, essentially, these aspects of life are inseparable. And now about two opposite parts. At one extreme is the artistic intelligentsia, which by chance, taking advantage of the fact that no one noticed this in time, began to call itself simply the intelligentsia, as if no other intelligentsia existed at all. I remember how once in the thirties Hardy 3 said to me with surprise: “Have you noticed how the words “intelligent people” are now being used? Their meaning has changed so much that Rutherford, Eddington, Dirac, Adrian 4 and I - we all seem to have ", we don't fit this new definition! This seems quite strange to me, don't you?" So, at one pole are the artistic intelligentsia, at the other are scientists, and, as the most prominent representatives of this group, physicists. They are separated by a wall of misunderstanding, and sometimes - especially among young people - even antipathy and enmity. But the main thing, of course, is misunderstanding. Both groups have a strange, twisted view of each other. They have such different attitudes to the same things that they cannot find a common language even in terms of emotions. Non-scientists tend to think of scientists as arrogant braggarts. They hear Mr. T.S. Eliot 5 - there is hardly a more expressive figure to illustrate this idea - talks about his attempts to revive the verse drama and says that although not many share his hopes, he and his associates will be glad if they can prepare the way for a new Kid or a new Green 6. This is the muted manner of expression that is accepted among the artistic intelligentsia; such is the restrained voice of their culture. And suddenly the incomparably louder voice of another typical figure reaches them. “This is the heroic age of science!” proclaims Rutherford. “The Elizabethan age has come!” Many of us have repeatedly heard similar statements and not so few others, in comparison with which those just cited sound very modest, and none of us doubted who exactly Rutherford predicted for the role of Shakespeare. But unlike us, writers and artists fail to understand that Rutherford is absolutely right; here both their imagination and their reason are powerless. Compare the words that are least like a scientific prophecy: “The last sounds the world will hear before its end will not be a roar, but a groan.” 7. Compare them with Rutherford’s famous witticism. "Lucky Rutherford, you are always on the wave!" - they told him once. “That’s true,” he replied, “but am I not the one who makes the waves? "There is a strong opinion among the artistic intelligentsia that scientists do not imagine real life and therefore they are characterized by superficial optimism. Scientists, for their part, believe that the artistic intelligentsia is devoid of the gift of providence, that it shows a strange indifference to the fate of humanity, that everything related to reason is alien to it, that it tries to limit art and thinking only to today's concerns, and so on. Anyone with the slightest prosecutorial experience could add to this list many other unspoken allegations. Some of them are not without foundation, and this applies equally to both groups of intelligentsia. But all these arguments are fruitless. Most of the accusations were born from the distorted 3 Hardy, Godfrey Harold () - English mathematician, known for his work on number theory, function theory and mathematical analysis, honorary member of the Russian Academy of Sciences. 4 E. Rutherford () and P.A. Dirac () - English physicists; A.S. Eddington () - English astrophysicist; E.D. Adrian () - physiologist. 5 T.S. Eliot () - English poet and critic. 6 T. Kyd () - one of the most famous playwrights of the 16th century; R. Green () - English poet, playwright and novelist. 7 Lines from the poem by T.S. Eliot "The Hollow Men", 1925.

3 understanding of reality, which is always fraught with many dangers. Therefore, now I would like to touch only on the two most serious of the mutual reproaches, one on each side. First of all, about the “superficial optimism” characteristic of scientists. This accusation is made so often that it has become commonplace. Even the most insightful writers and artists support it. It arose due to the fact that the personal life experience of each of us is taken as social, and the conditions of existence of an individual are perceived as a general law. Most of the scientists I know well, as well as most of my non-scientist friends, are well aware that the fate of each of us is tragic. We're all alone. Love, strong affections, creative impulses sometimes allow us to forget about loneliness, but these triumphs are only bright oases created by our own hands, and the end of the path always ends in darkness: everyone faces death alone. Some scientists I know find solace in religion. Maybe they feel the tragedy of life less acutely. I don't know. But most people, endowed with deep feelings, no matter how cheerful and happy they may be - the most cheerful and happy even to a greater extent than others - perceive this tragedy as one of the inalienable conditions of life. This applies equally to the people of science I know well, and to all people in general. But almost all scientists - and here a ray of hope appears - see no reason to consider the existence of humanity tragic simply because the life of each individual ends in death. Yes, we are alone, and everyone faces death alone. So what? This is our fate, and we cannot change it. But our lives depend on many circumstances that have nothing to do with fate, and we must resist them if we want to remain human. Most members of the human race suffer from starvation and die prematurely. These are the social conditions of life. When a person is faced with the problem of loneliness, he sometimes falls into a kind of moral trap: he plunges contentedly into his personal tragedy and stops worrying about those who cannot satisfy their hunger. Scientists usually fall into this trap less often than others. They are characterized by an impatient desire to find some way out, and usually they believe that this is possible until they are convinced of the opposite. This is their true optimism - the optimism that we all desperately need. The same will to goodness, the same persistent desire to fight alongside one’s blood brothers, naturally makes scientists treat with contempt the intelligentsia who occupy different social positions. Moreover, in some cases these positions really deserve contempt, although such a situation is usually temporary, and therefore it is not so typical.< >Number two is a dangerous number. Attempts to divide anything into two parts, naturally, should inspire the most serious fears. At one time I thought about making some additions, but then I abandoned this idea. I wanted to find something more than an expressive metaphor, but much less than a precise diagram of cultural life. For these purposes, the concept of “two cultures” fits perfectly; any further clarification would do more harm than good.

4 At one pole is the culture created by science. It really exists as a specific culture, not only in an intellectual sense, but also in an anthropological sense. This means that those involved do not need to fully understand each other, which happens quite often. Biologists, for example, quite often do not have the slightest idea about modern physics. But biologists and physicists are united by a common attitude towards the world; they have the same style and the same norms of behavior, similar approaches to problems and related starting positions. This community is amazingly broad and deep. She makes her way in defiance of all other internal connections: religious, political, class. I think that, upon statistical testing, there will be slightly more non-believers among scientists than among other groups of the intelligentsia, and in the younger generation there are apparently even more of them, although there are not so few believing scientists either. The same statistics show that the majority of scientists adhere to left-wing views in politics, and their number among young people is obviously increasing, although again there are many conservative scientists. Among scientists in England and, probably, the USA, there are significantly more people from poor families than among other groups of intellectuals. However, none of these circumstances has a particularly serious impact on the general structure of scientists' thinking and on their behavior. By the nature of their work and by the general structure of their spiritual life, they are much closer to each other than to other intellectuals who hold the same religious and political views or come from the same environment. If I were to venture into shorthand, I would say that they are all united by the future that they carry in their blood. Even without thinking about the future, they equally feel their responsibility to it. This is what is called common culture. At the other pole, the attitude to life is much more diverse. It is quite obvious that if one wants to make a journey into the world of the intelligentsia, going from physicists to writers, one will encounter many different opinions and feelings. But I think that the pole of absolute misunderstanding of science cannot but influence the entire sphere of its attraction. Absolute misunderstanding, widespread much more widely than we think - due to habit we simply do not notice it - gives a taste of unscientificness to the entire “traditional” culture, and often - more often than we think - this unscientificness almost crosses the brink of anti-science. The aspirations of one pole give rise to their antipodes at the other. If scientists carry the future in their blood, then representatives of “traditional” culture strive to ensure that the future does not exist at all. The Western world is governed by traditional culture, and the intrusion of science has only shaken its dominance to a negligible extent. The polarization of culture is a clear loss for all of us. For us as a people and for our modern society. This is a practical, moral and creative loss, and I repeat: it would be vain to believe that these three points can be completely separated from one another. However, now I want to focus on moral losses. Scientists and the artistic intelligentsia have ceased to understand each other to such an extent that it has become a ingrained anecdote. In England there are about 50 thousand scientists in the field of exact and natural sciences and about 80 thousand specialists (mainly engineers) engaged in the applications of science. During the Second World War and in the post-war years, my colleagues and I were able to interview thousands of both, that is, approximately 25%. This number is large enough to suggest a pattern, although most of those we interviewed were under forty years of age. We have some idea of what they are reading and thinking about. I admit that with all my love and respect for these people, I was somewhat depressed.

5 We were completely unaware that their ties to traditional culture had become so weakened that they were reduced to polite nods. It goes without saying that there have always been outstanding scientists, possessed of remarkable energy and interested in a wide variety of things; they still exist, and many of them have read everything that is usually talked about in literary circles. But this is an exception. Most, when we tried to find out what books they had read, modestly admitted: “You see, I tried to read Dickens...” And this was said in such a tone as if we were talking about Rainer Maria Rilke, that is, about an extremely complex, accessible writer understood only by a handful of initiates and hardly worthy of real approval. They really treat Dickens like they treat Rilke. One of the most amazing results This survey was probably the discovery that Dickens's work has become an example of incomprehensible literature. When they read Dickens or any other writer we value, they only nod politely to traditional culture. They live by their full-blooded, well-defined and constantly developing culture. It is distinguished by many theoretical positions, usually much clearer and almost always much better substantiated than the theoretical positions of writers. And even when scientists do not hesitate to use words differently from writers, they always give them the same meaning; if, for example, they use the words “subjective”, “objective”, “philosophy”, “progressive”, then they know perfectly well what they mean, although they often mean something completely different from everyone else. Let's not forget that we are talking about highly intelligent people. In many ways, their strict culture is admirable. Art occupies a very modest place in this culture, albeit with one, but very important exception - music. Exchanges of opinions, intense discussions, long-playing records, color photography: a little for the ears, a little for the eyes. Very few books, although probably not many, have gone as far as a certain gentleman, who is obviously on a lower rung of the scientific ladder than the scientists I have just spoken of. This gentleman, when asked what books he read, answered with unshakable self-confidence: “Books? I prefer to use them as tools.” It is difficult to understand what kind of tools he “uses” them as. Maybe as a hammer? Or shovels? So, there are still very few books. And almost nothing from those books that constitute the daily food of writers: almost no psychological and historical novels, poems, plays. Not because they are not interested in psychological, moral and social problems. Scientists, of course, come into contact with social problems more often than many writers and artists. In moral terms, they, in general, constitute the healthiest group of intellectuals, because the idea of justice is embedded in science itself and almost all scientists independently develop their views on various issues of morality and morality. Scientists are interested in psychology to the same extent as most intellectuals, although sometimes it seems to me that their interest in this area appears relatively late. So it's obviously not a matter of lack of interest. Much of the problem is that the literature associated with our traditional culture is considered "irrelevant" by scholars. Of course, they are sadly mistaken. Because of this, their imaginative thinking suffers. They are robbing themselves.

6 And the other side? She also loses a lot. And perhaps its losses are even greater because its representatives are more vain. They still pretend that traditional culture is all culture, as if the status quo doesn't really exist. It’s as if trying to understand the current situation is of no interest to her, either in itself or from the point of view of the consequences to which this situation can lead. As if the modern scientific model of the physical world, in its intellectual depth, complexity and harmony, is not the most beautiful and amazing creation created by the collective efforts of the human mind! But most of the artistic intelligentsia do not have the slightest idea about this creation. And she can’t have it, even if she wanted to. It seems that as a result of a huge number of sequential experiments, a whole group of people who did not perceive certain sounds was eliminated. The only difference is that this partial deafness is not a congenital defect, but the result of training - or rather, lack of training. As for the semi-deaf themselves, they simply do not understand what they are missing. When they hear about some discovery made by people who have never read the great works of English literature, they chuckle sympathetically. To them, these people are simply ignorant specialists whom they discount. Meanwhile, their own ignorance and the narrowness of their specialization are no less terrible. Many times I have been in the company of people who, according to the norms of traditional culture, are considered highly educated. Usually they are very passionately indignant at the literary illiteracy of scientists. One day I couldn’t resist and asked which of them could explain what the second law of thermodynamics is. The answer was silence or refusal. But asking this question to a scientist means about the same as asking a writer: “Have you read Shakespeare?” Now I am convinced that if I had been interested in simpler things, for example, what mass is or what acceleration is, that is, I would have sunk to that level of scientific difficulty at which in the world of the artistic intelligentsia they ask: “Can you read?” then no more than one in ten highly cultured people would understand that we speak the same language. It turns out that the magnificent edifice of modern physics is rising upward, and for most of the insightful people of the Western world it is as incomprehensible as it was for their Neolithic ancestors. Now I would like to ask one more question from among those that my writer and artist friends consider the most tactless. At the University of Cambridge, professors of science, science and humanities meet each other for lunch every day. About two years ago 8 one of the most remarkable discoveries in the history of science was made. I don't mean satellite. The launch of the satellite is an event that deserves admiration for completely different reasons: it was proof of the triumph of organization and the limitless possibilities of applying modern science. But now I'm talking about Yang and Lee's discovery. The research they carried out is remarkable for its amazing perfection and originality, but its results are so terrifying that you involuntarily forget about the beauty of thinking. Their work has forced us to reconsider some of the fundamental laws of the physical world. Intuition, common sense - everything was turned upside down. The result they obtained is usually formulated as non-conservation of parity 9. If 8 That is, around 1957 9 Until 1956, it was considered self-evident that physical processes can't change if we replace the world its mirror image. However, Lee and Yang suggested that for some interactions of elementary particles the situation is different, that is, that in the microcosm there is

7 there were living connections between the two cultures; this discovery would be talked about at every professor's table in Cambridge. But in reality - did they say? I was not in Cambridge at the time, and this was precisely the question I wanted to ask. It seems that there is no basis at all for the unification of the two cultures. I'm not going to waste my time talking about how sad this is. Moreover, in fact, this is not only sad, but also tragic.< > For our mental and creative activity, this means that the richest opportunities are wasted. A clash of two disciplines, two systems, two cultures, two galaxies - if you are not afraid to go that far! - cannot help but strike a creative spark. As can be seen from the history of the intellectual development of mankind, such sparks have indeed always flared up where habitual connections have been severed. For now, we continue to pin our creative hopes primarily on these flares. But today our hopes are unfortunately up in the air because people belonging to two cultures have lost the ability to communicate with each other. It is truly surprising how superficial the influence of 20th century science on modern art turned out to be. From time to time, one comes across poems in which poets deliberately use scientific terms, and usually incorrectly. At one time, the word “refraction” came into fashion in poetry, acquiring an absolutely fantastic meaning. Then the expression “polarized light” appeared; from the context in which it is used, one can understand that the writers believe that this is some kind of especially beautiful light. It is absolutely clear that in this form science can hardly bring any benefit to art. It must be accepted by art as an integral part of our entire intellectual experience and used as freely as any other material. I have already said that the demarcation of culture is not a specifically English phenomenon - it is characteristic of the entire Western world. But the point, obviously, is that in England it manifested itself especially sharply. This happened for two reasons. First, because of the fanatical belief in specialization of learning, which has gone far further in England than in any other country, Western or Eastern. Secondly, because of the characteristic tendency in England to create unchanging forms for all manifestations of social life. As economic inequality is leveled out, this trend does not weaken, but intensifies, which is especially noticeable in the English education system. In practice, this means that as soon as something like a division of culture occurs, all social forces contribute not to eliminating this phenomenon, but to consolidating it. The split in culture became an obvious and alarming reality 60 years ago. But in those days, the Prime Minister of England, Lord Salisbury, had a scientific laboratory in Hatfield, and Arthur Balfour 10 was interested in natural sciences much more seriously than just an amateur. John Andersen 11, before entering public service, was engaged in research in the field of inorganic chemistry in Leipzig, being simultaneously interested in so many scientific disciplines that now it seems simply unthinkable. fundamental difference between “left” and “right”. Subsequently, special experiments showed that they were right 10 A. J. Balfour () - English philosopher and major statesman. 11 J. Andersen () - politician in England.

8 Nothing like this is to be found in the highest spheres of England these days; Now even the very possibility of such an interweaving of interests seems absolutely fantastic. Attempts to build a bridge between scientists and non-scientists in England look now - especially among young people - much more hopeless than thirty years ago. At that time, the two cultures, which had long since lost the ability to communicate, still exchanged polite smiles, despite the chasm that separated them. Now politeness is forgotten, and we exchange only barbs. Moreover, young scientists feel involved in the blossoming that science is now experiencing, and the artistic intelligentsia suffers from the fact that literature and art have lost their former importance. Aspiring scientists are also confident - let's be rude - that they will get a well-paid job, even without particularly high qualifications, while their comrades specializing in English literature or history will be happy to receive 50% of their salary. No young scientist of the most modest abilities suffers from the consciousness of his own uselessness or from the meaninglessness of his work, like the hero of "Lucky Jim" 12, and in fact, in essence, the "angry" of Amis and his associates is to some extent caused by the fact that The artistic intelligentsia is deprived of the opportunity to fully use their powers. Snow C.P. Two cultures. // Collection of journalistic works. M., S “Lucky Jim” is a novel by the English writer K. Amis, published in Russian in the magazine “Foreign Literature” (10-12, 1958).

Questions to ask yourself. There are no right or wrong answers to them. Because sometimes it's right asked question there is already an answer. Hello, Dear Friend! My name is Vova Kozhurin. My life

1 1 New Year What do you expect from the coming year? What goals do you set for yourself, what plans and desires do you have? What do you expect from a magical diary? 8 My goal is to help you acquire the main magical

1. Two cultures http://vivovoco.rsl.ru/vv/papers/ecce/snow/twocult.htm TWO CULTURES AND THE SCIENTIFIC REVOLUTION Charles Percy Snow Reproduced from the publication: Ch.P. Snow, Portraits and Reflections, M., Ed. "Progress",

I am a teacher. I consider the teaching profession to be the most important in the world. Teaching is an art, work no less creative than the work of a writer and composer, but more difficult and responsible. The teacher speaks to the soul

MOURNING THE LOSS OF SOMEONE VERY SIGNIFICANT Created by Marge Heegaard Translated by Tatiana Panyusheva To be completed by children Name Age You have gone through a very difficult time. And the fact that your thoughts and feelings are confused

BULLETIN OF TOMSK STATE UNIVERSITY 2009 Philosophy. Sociology. Political Science 4(8) IS EXISTENCE A PREDICATE? 1 The meaning of this question is not entirely clear to me. Mr. Neal says that existence

Hello dear friends and readers of the site www.raduga-schastie.ru. It so happens that in our lives the ability to communicate plays a very important role. And this skill is much more important than excellent grades in mathematics

I would like to ask - why is it so difficult to meet a man once and for all? Why do some people do it easily, while others wait in vain for years? And if I meet a person, how do I know it’s him??? Nelya Nelya,

I was sent an interesting video document “The Power of the Mind”. At first glance, very thoughtful reasoning. But in fact, this follower of Buddhism expounds the truths of his religion. "The feeling of myself waking up

YOUR GOAL IS TO SHOW GROWTH POSSIBILITIES AND INDICATE THE NECESSARY TOOLS (Different paths of Ascension into the Light) 03.21.2019 1 / 8 Me: Can we somehow influence the political situation in the world? Lucifer: You can consciously

Love and Devotion Self-Respect Om Shri Paramatmane Namaha Love and Devotion Question: As a child, I was raised Catholic. In this approach there is fear of God and fear of sin i.e. what

Identifying Limiting Beliefs Excerpt from Jack Makani's new book, Self-Coaching: 7 Steps to a Happy, Mindful Life Shamans believe, “The world is what we make it out to be.” If so, then follow

What is culture? Memory of culture. basis Timofeeva Tamara Vasilievna, teacher of Russian language and literature, GBOU school 627 Nevsky district of St. Petersburg “The culture of humanity does not move forward through

CHAPTER A 9 About Imperfection Things are getting better. There will be no end to this. Things are getting better and better, and there is beauty in that. Life is eternal and knows nothing of death. When something is perfect, it is finished

The three minds model, or why some of your important goals are not being realized? Jack Makani If you look at the ancient traditions that exist in different cultures, then in almost all traditions we can

Lesson 1 You have started new life What happens when a caterpillar becomes a butterfly? How does a seed grow into a mighty tree? The laws of nature control these processes and produce these amazing changes.

A. Einstein THE NATURE OF REALITY Conversation with Rabindranath Tagore Einstein A. Collection scientific works. M., 1967. T. 4. P. 130 133 Einstein.

MINISTRY OF HEALTH OF THE REPUBLIC OF DAGESTAN GBPOU RD "DAGESTAN BASIC MEDICAL COLLEGE" METHODOLOGICAL MANUAL on the topic: "PECULIARITIES OF THE ADAPTATION PERIOD IN THE NEW TEAM" Compiled by Yusupova

The essay is written according to a specific plan: 1. Introduction 2. Statement of the problem 3. Commentary on the problem 4. Author’s position 5. Your position 6. Literary argument 7. Any other argument 8. Conclusion

Psychology of relationships Psychology about relationships The easiest way to explain this paradoxical fact is that there are still ill-mannered people who have not been instilled with good manners since childhood. But it's not only

November 1972 1 November 2, 1972 (Conversation with Sujata) How is Satprem? I think ok, dear Mother. And you, how are you doing? And I wanted to ask: how are things going with dear Mother? Mother is not “coming”! No more personality

A N T U A N D E S E N T - E K Z Y P R I M A L E N K I Y PRINC LEON VERT I ask the children to forgive me for dedicating this book to an adult . I'LL SAY IN JUSTIFY: THIS ADULT IS MY BEST