Durer square solution. Zodiac of Johann Kleberger. Astronomy and magic in Durer's painting. Large magic squares

Durer Albrecht (1471-1528), German painter, draftsman, engraver, art theorist.

studied with his father.

The father, a jewelry maker, wanted to involve his son in working in a jewelry workshop, but Albrecht did not express any desire. He loved and was drawn to painting.

From the Nuremberg artist Wolgemut Dürer mastered not only painting, but also engraving on wood.

Inspired by the works of the artist Martin Schongauer, whom he never met, Albrecht traveled a lot and studied, studied, studied everywhere...

But the time came when Albrecht needed to get married. And then he chose Agnes Frey, the daughter of his father’s friend, from an old and respected Nuremberg family. The marriage with Agnessa was childless, and the spouses were different in character, which made the family not very happy.

But nevertheless, he opened his own business and created a significant part of his engravings in his workshop.

Rumors circulated in Venice about his love for both sexes...Perhaps Dürer practiced same-sex love with his dear friend, an expert on ancient literature, Pirkheimer.

Long, hot-curled hair, dancing lessons, fear of contracting syphilis in Venice and buying medicine against this disease in the Netherlands, elegant clothes, petty vanity in everything related to his beauty and appearance, melancholy, narcissism and exhibitionism, a Christ complex, a childless marriage, submission to his wife, a tender friendship with the libertine Pirkheimer, whom he himself, in an October letter of 1506, jokingly proposed to castrate -

All this is combined in Dürer with tender care for his mother and brothers, with many years of hard work, frequent complaints about poverty, illness, and misfortunes that allegedly haunted him.

Be faithful to God!

Get healthy

And eternal life in heaven

Like the most pure Virgin Mary.

Albrecht Durer tells you -

Repent of your sins

Before last day fasting

And shut the devil's mouth,

You will defeat the evil one.

May the Lord Jesus Christ help you

Confirm yourself in goodness!

Think about death more often

About the burial of your bodies.

It frightens the soul

Distracts from evil

And the sinful world,

From the oppression of the flesh

And the devil's instigations...

When Koberger published in 1498"Apocalypse",

Dürer created 15 woodcuts, which brought him European fame. Acquaintance with the Venetian school had a strong influence on the artist’s painting style.

In Venice, the artist commissioned German merchants "Festival of Rose Wreaths" and then other proposals came, paintings that left an indelible impression with the versatility of colors and subjects.

The Emperor himself Maximilian I

was in awe of the art of Albrecht Durer.

Dürer adhered to the views of “iconoclasts,” however, in A. Dürer’s later works, some researchers find sympathy for Protestantism.

At the end of his life, Dürer worked a lot as a painter; during this period he created the most profound works, which manifest his familiarity with Dutch art.

One of the most important paintings recent years — diptych "Four Apostles", which the artist presented to the city council in 1526.

In the Netherlands, Dürer fell victim to an unknown disease (possibly malaria), from which he suffered for the rest of his life.

Albrekh composed the so-called magic square, depicted in one of his most perfect engravings -"Melancholia" Durer's merit lies in the fact that he managed to fit the numbers from 1 to 16 into the drawn square in such a way that the sum 34 was obtained not only by adding the numbers vertically, horizontally and diagonally, but also in all four quarters, in the central quadrilateral and even when adding the four corners cells. Dürer also managed to include in the table the year the engraving was created “"(1514).

There are three famous woodcuts in the works of Albrecht Dürer, depicting maps of the southern and northern hemispheres of the starry sky and the eastern hemisphere of the Earth, which became the first in history to be printed in a typographical way.

In 1494, Sebastian Brant's book was published under the symbolic title"Ship of Fools"

(Das Narrenschiff oder das Schiff von Narragonia).

During the obligatory journeys along the Rhine for a guild apprentice, Dürer completed several easel engravings in the spirit of late Gothic, illustrations for “Ship of Fools” by S. Brant,

on which the fleet crosses the sea. There are a lot of fools around. Here they laugh at the foolish sailors and ships of the Empire.

It is believed that in addition to A. Dürer, several draftsmen and carvers worked on the project simultaneously... Painting "Ship of Fools"- wrote the famous artistHieronymus Bosch.

Durer's drawing "Ship of Fools"

Above on the right there are fools on a cart, below a ship surrounded by boats is sailing on the sea, and on the ship and in the boats there are all fools.

Many illustrations for “The Ship of Fools,” as commentators note, have LITTLE CONNECTION WITH THE CONTENT OF THE BOOK ITSELF.

As it turns out, Brant’s book itself was chosen only as a reason, a pretext, for publication large number engravings (one hundred and sixteen) on the theme "Ship of Fools".

Have Albrecht Durer and such a painting as

"Feast of All Saints"

(Landauer Altar) 1511. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. This painting also brought great fame to the artist.

There is a certain engraving “Melancholy”, owned by the German artist Albrecht Durer, which is better known to mathematicians and occultists than to those interested in painting.

At least - you can check this - very little has been written about it on the Internet. But this is a really cool thing. And the only more or less detailed source is Dan Brown’s book “The Lost Symbol”.

I read this book and neither the plot nor the square stuck in my head. And then it suddenly popped up from an unexpected direction.

Engraving “Melancholy” - pay attention to the square in the upper right corner:

Here it is larger:

The essence of all “magic squares” is generally clear: the sum of the columns and diagonals is equal to some number. So it is here. This number is 34. But the fact is that this number appears in absolutely ANY scenario. The sum of the upper left square is 34, the same is true for the upper right, lower right and lower left small squares. And also the central square - 10+11+6+7=34. And also, if you add the corner numbers 16,13, 4 and 1, you also get 34.

And also, if you start laying a line from 1 to 16, you will get this absolutely symmetrical (and in a mirror relation!) figure:

And at the very bottom, the numbers 15 and 14 indicate the date of creation of the engraving - 1514. And the numbers in bottom corners— 4 and 1 — digital designations of the artist’s initials: D A — Dürer Albrecht.

All this mathematical “palmistry”, according to some, indicates that Dürer created his square not by poking or picking, but by using other measurements. In the sense - going beyond 3 dimensions and.... somehow on the seventh-dimensional(????) level?…. Perhaps with the help of the so-called “conchoids” or “shells,” as Dürer called it (in his mathematical monograph “Guide to Measuring with Compass and Ruler,” published in 1525) and of which he was the author, he created his “magic square.”

"Conchoid":

And pay attention to the stone in the engraving - a parallelepiped truncated at two corners, the side faces of which are 2 regular triangles and 6 pentagons:

Robert Langdon, the symbolist detective in Dan Brown's The Lost Symbol, superimposes the 16-digit cipher from the base of the Masonic pyramid onto the Durer square and receives the decryption:

that is, JEOVA SANCTUS UNUS - the One True God.

Dürer in all likelihood belonged to a certain Secret Society. And perhaps he possessed some secret sacred knowledge...

Or maybe this is all a hoax?!..

Let's draw 16 cells and put numbers from 1 to 16 in them in order. Now just swap 1 and 16, 4 and 13 (these are the corners), 6 and 10 and 7 and 11 (the square in the middle). And also 2 and 3 and 14 and 15 standing next to each other.

VOILA! This is the magic square of the coolest degree. Just? Just! But guess what and how to change... On the other hand, the absolute symmetry of replacing numbers cannot but suggest the simplicity and universality of the solution. Or is it easy for us to reason now, but Dürer needed to use his conchoid (see above) to understand how and what to swap places?...

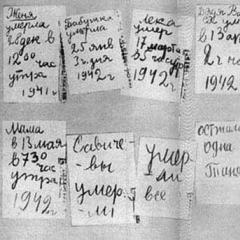

The correction in the engraving, which Dürer INTENTIONALLY left so obvious, can be seen with the naked eye:

When replacing the numbers in the square drawn for us from 1 to 16 in order, only the side 5 and 9 on the left and 8 and 12 on the right remain unchanged. Initially, Dürer wanted to swap them too, but this turned out to be unnecessary. Why did he leave his mistake for everyone to see? Show me how your thoughts work? Vanity? And the year 1514, which fits so well into the square, is also a merit or did the artist simply wait for the desired date for greater effect, having thought through all the mathematics earlier?))

Maybe so. Even the fields of higher mathematics can be explained by the vanity of an artist who considered himself handsome and regularly painted his self-portraits so that everyone could admire him.

Returning to Melancholia, magic squares and the occult. The engraving was written for Emperor Maximilian I (for those who know, the husband of Mary of Burgundy, son-in-law of Charles the Bold and grandfather of Emperor Charles V).

Here is his portrait, also by Durer:

Maximilian considered himself melancholic. In the Middle Ages (and even now) it was believed that melancholic people were influenced by the planet Saturn. The magic square was supposed to be a kind of talisman that would ward off the dark influence of Saturn, while simultaneously attracting the more positive energy of Jupiter.

In general, you can write a lot about this engraving. You can still consider all the attributes - but that’s for another time. In this case, mathematics seemed more interesting to me than painting.

The magic square, reproduced by the German artist Albrecht Durer in the engraving “Melancholy”, is known to all researchers of magic squares.

Square in its usual form (Fig. 6.1):

Figure 6.1

Interestingly, the two middle numbers in the last line of the square (they are highlighted) make up the year the engraving was created - 1514.

It is believed that this square, which so fascinated Albrecht Durer, came to Western Europe from India at the beginning of the 16th century. In India, this square was known in the 1st century AD.

It is believed that magic squares were invented by the Chinese, since the earliest mention of them is found in a Chinese manuscript written 4000-5000 BC. That's how old magic squares are!

Let us now consider all the properties of this amazing square. But we will do this on another square, the group of which includes the Durer square.

This means that the Dürer square is obtained from the square that we will now consider by one of the seven main transformations of magic squares, namely a rotation of 180 degrees. All 8 squares that form this group have properties that will now be listed, only in property 8 for some squares the word “row” will be replaced by the word “column” and vice versa.

You can see the main square of this group in Fig. 6.2.

Figure 6.2

Properties of this square:.

Property 1. This square is associative, that is, any pair of numbers symmetrically located relative to the center of the square gives a sum 17=1+n2.

Property 2. The sum of the numbers located in the corner cells of the square is equal to the magic constant of the square - 34 .

Property 3. The sum of the numbers in each corner 2x2 square, as well as in the central 2x2 square, is equal to the magic constant of the square.

Property 4. The magic constant of a square is equal to the sum of the numbers on opposite sides of the two central 2x4 rectangles, namely: 14+15+2+3=34, 12+8+9+5=34.

Property 5. The magic constant of the square is equal to the sum of the numbers in the cells marked by the move of the chess knight, namely: 1+6+16+11=34, 14+9+3+8, 15+5+2+12=34 and 4+10+13 +7=34.

Property 6. The magic constant of a square is equal to the sum of the numbers in the corresponding diagonals of the 2x2 corner squares adjacent to the opposite vertices of the square.

For example, in the 2x2 corner squares, which are highlighted in Fig. 4, the sum of the numbers in the first pair of corresponding diagonals: 1+7+10+16=34 (this is understandable, since these numbers are located on the main diagonal of the square itself). The sum of the numbers in the other pair of corresponding diagonals: 14+12+5+3=34.

Property 7. The magic constant of the square is equal to the sum of the numbers in the cells marked by a move similar to the move of a chess knight, but with an elongated letter G. I show these numbers: 1+9+8+16=34, 4+12+5+13=34, 1+2 +15+16=34, 4+3+14+13=34.

Property 8. In each row of the square there is a pair of adjacent numbers, the sum of which is 15, and another pair of adjacent numbers, the sum of which is 19. In each column of the square there is a pair of adjacent numbers, the sum of which is 13, and another pair of also adjacent numbers , the sum of which is 21. brain cell square sudoku

Property 9. The sums of the squares of the numbers in the two outer rows are equal to each other. The same can be said about the sums of the squares of the numbers in the two middle rows. See:

12 + 142 + 152 + 42 = 132 + 22 + 32 + 162 = 438

122 + 72 + 62 + 92 = 82 + 112 + 102 + 52 = 310

Numbers in the columns of a square have a similar property.

Property 10. If we inscribe a square with vertices in the middle of the sides into the square under consideration (Fig. 6.3), then:

- · the sum of the numbers located along one pair of opposite sides of an inscribed square is equal to the sum of the numbers located along the other pair of opposite sides, and each of these sums is equal to the magic constant of the square;

- The sums of squares and sums of cubes of the indicated numbers are equal:

- 122 + 142 + 32 + 52 = 152 + 92 + 82 + 22 = 374

- 123 + 143 + 33 + 53 = 153 + 93 + 83 + 23 = 4624

Figure 6.3

These are the properties of the magic square in Fig. 5.2

It should be noted that in an associative square, which is the square in question, you can also perform such transformations as rearranging symmetrical rows and/or columns. For example, in Fig. 5.4 shows a square obtained from the square in Fig. 4 by rearranging the two middle columns.

Figure 6.4

In the new associative squares obtained by such transformations, not all of the properties listed above are satisfied, but many of the properties hold. Readers are invited to check the fulfillment of the properties in the square shown in Fig. 6.4.

1. Ambiguity in reading old dates. "Magic Square" by Albrecht Durer

The most important formal result of NH, obtained by applying independent mathematical and statistical dating methods to the material of the Scaligerian version of the history of antiquity and the Middle Ages, is the discovery of the system of chronological shifts underlying it. As a result of one of these shifts, clearly expressed in European and Russian medieval history, many events, documents and works of art of the XII-XVII centuries were artificially thrown back about a century into the past. In addition to this, it is shown that a comfortable (and familiar) to modern man) the positional decimal system of recording numbers was first invented not in the deepest (almost in the 3rd millennium BC) antiquity, as the Scaligerian chronology claims, but only somewhere in the middle of the 16th century. And almost immediately, on the basis of Russian cursive writing, which was used in the then more primitive semi-positional (which did not have a zero) Slavic-Greek number system, the familiar numbers from 0 to 9 arose, today called “Arabic” or “Indian”. Moreover, - and now for us this is the most important point - Initially, the symbols that later began to be used to write the numbers 5 and 6 had a different meaning: the number 5 at first meant six, and the number 6, on the contrary, meant five.

Taken together, the following follows from all this: “records using “Indo-Arabic” numerals in their modern form cannot be dated back to an era earlier late XVI century. If we are told today that a contemporary document has been dated in the form accepted today: 1250, or 1460, or even 1520, then this is a fake. Either the document was falsified, or the date was falsified, that is, it was backdated. And in the case of supposedly sixteenth-century dates... probably some of them actually date back to the seventeenth century.

Vivid evidence of the latter, happily preserved in the famous engraving of Albrecht Durer “Melancholy”, fig. 1.

Rice. 1. Engraving by Albrecht Durer “Melancholy I”

This engraving depicts the so-called “magic square”, that is, a square table filled with various numbers in such a way that the sum of the numbers in each row, each column and on both diagonals is the same (and, in this case, equals thirty-four). But, taking a closer look at these numbers, it is easy to see that the number five in the first column of the second row (which should be there for the square to turn out “magic”) was drawn (more precisely, cut out on an engraving board) on top of the six that was originally located here, Fig. . 2.

Rice. 2. “Magic square” in Durer’s engraving (left) and a five converted from a six (right). Enlarged fragments of Fig. 1

2. Dürer’s portrait of Johann Kleberger and the zodiac depicted on it

However, Dürer’s “magic square”, as it turns out, is not at all the only echo of its kind that conveys to us the true primary meaning of the numbers 5 and 6. Exactly the same effect of their incorrect reading - and, this time, related to the recording of the date ! - is revealed, upon careful examination, in another work by the same artist. We are talking about a relatively small (37 by 37 cm) portrait of the Nuremberg merchant and banker Johann Kleberger, who allegedly lived in 1485/86-1546, fig. 3.

Rice. 3. Portrait of Johann Kleberger. Painting by Albrecht Dürer dating from 1526. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

It is believed that this portrait was painted by order of the latter by Albrecht Dürer in 1526, which seems to be directly evidenced by the corresponding inscription in the upper right corner: “1526” and under it Dürer’s monogram. However, as follows from the above, this inscription, in fact, may indicate not 1526, but 1625 AD. But is it possible to test this assumption? Answer: yes, in this case this turns out to be possible, since, in addition to the digital one visible to everyone, the same portrait also contains at least one more - hidden from a quick glance - date, recorded astronomically and placed in its upper left corner, Fig. . 4.

Rice. 4. “Astronomical” (left) and “digital” (right) dates on the portrait of Johann Kleberger. Enlarged fragments of Fig. 3

One glance at the left fragment of the figure is enough. 4, in order to understand that before us is a completely frank horoscope. In fact, we see here six stars representing six planets, as well as the Sun, represented as a bright yellow glow, Fig. 5-12.

Rice. 5. Calendar with the Ptolemaic system of the world. An interesting feature of this diagram, which distinguishes it from other similar images, is that it has a clearly expressed “magical” character: each of the signs of the Zodiac is accompanied by a certain symbol, which, in the opinion of the compiler, had

“magical” nature (what these symbols are will be discussed below). Illustration from a medieval astrological manuscript (Bavarian State Library, Codex BSB Clm 826)

Rice. 6. Sun, Moon and five star-planets. In the center is a comet heading towards the Sun. Enlarged fragment of Fig. 5

Rice. 7. The seven liberal arts and their patron planets. On the left are Saturn (geometry) and Jupiter (logic). In the center (and in the enlarged fragment on the right) are represented: Mars (arithmetic), Sun (grammar) and Venus (music). Shown on the right: Mercury (physics) and Moon (rhetoric).

At the bottom there are images of planets and days of the week, conventionally designated by seven lamps. Illustration from the Tübingen House Book - a medical-astrological manuscript supposedly from the 15th century

(Tübingen University Library, Code Md 2)

Rice. 8. Zodiac person. A diagram illustrating medieval ideas about the influence exerted on human organs by the signs of the Zodiac (left, above and below) and the planets (right). Illustration from a book of hours from the mid-16th century

Rice. 9. The sun and six star-planets on the title page of an alchemical treatise: Johann Mylius, Anatomia Auri, sive Tyrocinium medico-chymicum, Frankfurt, 1628

Rice. 10. Jean Gerson (theologian and chancellor of the University of Paris, who allegedly lived in 1363-1429) in the image of a pilgrim. On the right is an enlarged fragment with a shield depicting the Sun, Moon and five star-planets. Engraving allegedly from the late 15th century, attributed to Albrecht Dürer

Rice. 11. Rider-Sun. Illustration from a festival book from the late 16th century (BSB Cod. icon. 340)

Rice. 12. The sun in an engraving by Hans Weiditz. Allegedly mid-16th century

The only ambiguity arises in connection with determining the meaning of the symbol depicted in the center of the entire composition. At first glance, this is a generally accepted astronomical sign of the constellation Leo, present as such in countless images, Fig. 13-14, including on the famous star map of the same Dürer, fig. 15.

Rice. 13. Sun and Leo. Above the lion's back is its symbol. Engraving by Virgilius Solis. Allegedly mid-16th century

Rice. 14. Sun with Leo (left) and an enlarged fragment with the symbol of the latter (right). Drawing by Erhard Schon. Allegedly 1536

Rice. 15. Image of Leo on Durer’s star map (left) and its fragments with the symbol of this constellation (right). Allegedly 1515

It is interpreted as a symbol of Leo in almost all descriptions of the painting in question. However, as stated in - and, as will become clear later, this is almost certainly the case - in this particular case this symbol has a narrower meaning and does not indicate the entire constellation Leo, but only its main star - Regulus .

3. The first version of the horoscope is “with Leo”. When was Kleberger's portrait actually painted?

Let's first consider the first - standard - possibility.

In this case we get that in Fig. 4 presents an extremely laconic horoscope - all planets are in Leo. The question arises: in what years did all seven planets known in medieval astronomy gather in the starry sky in the constellation Leo? The HOROS program gives the following comprehensive answer to it: over the last thousand years this happened only twice - August 14-16, 1007 AD. and August 30 - September 1 old style 1624 AD. The first solution, for obvious reasons, obviously disappears, but the second turns out to be literally one year away from the date recorded by the artist in the picture, Fig. 4, provided that the numbers 5 and 6 had not their current meaning for him, but their original meaning.

There is an excellent correspondence. It turns out that at the end of August - beginning of September 1624, some important event took place for Johann Kleberger, in memory of which he ordered Durer (maybe immediately, maybe a little later) the portrait in question, and the latter soon fulfilled this order.

However, this is only a preliminary conclusion, following from a purely formal result, which relates the above date specifically to 1624 and does not take into account the fact that in earlier times the beginning of the year was not always and everywhere counted, as is customary for us today, from the first of January. In particular, in Rus' in the era of the 16th-17th centuries that interests us now New Year started in September. And if, taking into account this circumstance, we assume that the customer of the portrait followed, at least in this particular case, this old (originating in “Ancient” Egypt) tradition of counting the new year from September, then the picture becomes much more interesting.

Namely, two possible options arise, depending on whether he accepted (again, at least in the case under consideration) the relatively recently carried out - forty years earlier - Gregorian calendar reform and the introduction of the “new style”. If so, then ten days should be added to the above date, and it turns out that the horoscope depicted in the portrait contains the date September 9-11 (new style), falling in the first month of the year September 1625. That is, astronomical and digital records, Fig. 4 will turn out to be (partially, since the first is more accurate) duplicating each other and pointing to the same year 1625.

If this was not the case, and the customer of the painting adhered to the old Julian counting of days, then the result becomes completely amazing, since in this case August 31 and September 1 fall exactly on the last day of 1624 and the first day of 1625 of the September year. And then it turns out that the zodiac in Fig. 3 is New Year's, and the portrait itself was painted on the occasion of the new year of 1625, with the beginning of this year in September.

In Fig. Figure 16 shows a “snapshot” of the starry sky on New Year’s morning, September 1625, obtained using the StarCalc planetarium program.

Rice. 16. Position of the planets in the morning (two hours after sunrise) September 1st Art. Art. (September 11 AD) 1624 AD The observation location is Nuremberg.

Thus, we have three options, assigning the “zodiac” date recorded in the painting, depending on the possible calendar ideas of its customer, to the end of the eighth month of January 1624, the end of the first ten days of the first month, or exactly to the beginning of September 1625.

A natural question arises: which of these options best corresponds to the image in Fig. 3? As we will now see, it is the latter, since it is with it that a number of other details of the picture under consideration are ideally consistent.

4. “Year of Saturn” and the symbolic meaning of the “lion” horoscope

First of all, let's look at the two figures depicted in the lower left and right corners of the portrait, Fig. 17, and let's try to understand what they mean.

Rice. 17. Figures at the bottom of the portrait of Johann Kleberger. Enlarged fragments of Fig. 3

With the left one - the clover shamrock growing on the top of the mountain - no questions arise. This is an ordinary coat of arms with the symbols of the owner. Exactly the same symbol can be seen in another surviving image of Johann Kleberger (by the way, his very name comes from clover), fig. 18.

Rice. 18. Johann Kleberger on a medal from an unknown Nuremberg master, dated, like the portrait of Dürer, to 1526. On the reverse side you can see a helmet, above which there is a picture of a mountain with a trefoil growing on its top.

But what exactly does right mean? Of course, it is quite possible to say that this is “just Nice picture, steam room to the shield,” and be satisfied with that. However, taking into account the above, in this picture it is easy to recognize an astronomical plot slightly veiled under heraldic style. In fact, we see here a long-bearded old man holding two shamrocks in his hands. The background to this composition suggests itself: six identical leaves (as well as six identical stars in the opposite corner of the same portrait, Fig. 4) most likely represent six planets, Fig. 19-21, and the old man - some seventh planet.

Rice. 19. Planetary tree. Title page alchemical treatise: Basilius Valentinus, Occulta Philosophia, Frankfurt am Mayn, 1613

Rice. 20. Planets (also known as alchemical elements), depicted as leaves on the branches of a tree.

Enlarged fragment of Fig. 19

Rice. 21. Sun, Moon and planets on the branches of the alchemical tree. Illustration from the treatise: Johann Mylius, Philosophia Reformata, Frankfurt, 1622

The question is, which one specifically? Obviously, this is either Jupiter or Saturn, since these two planets were most often (and the latter almost always) depicted in this form, Fig. 22.

Rice. 22. Jupiter (left) and Saturn (right) in engravings by Hans Burgkmair. Allegedly the end of XV - beginning of XVI century

Strictly speaking, more or less similar images are sometimes found for Mars, Mercury and the Sun, but they always have signatures or characteristic attributes (the sword of Mars, the winged staff of Mercury, etc.) that make it possible to understand which planet is meant , rice. 13. In the absence of such attributes, it is Jupiter and Saturn that remain, since the only sign for identification, in this case, turns out to be age itself, and the latter are the eldest among the “planetary” gods.

So, let's consider the first option. In this case, it turns out that the six planets are divided into two triplets, depicted as trefoils in the hands of the elder Jupiter. From an astronomical point of view, this means that three planets should be on one side of Jupiter, and three on the other. But this is exactly how things stood in the “New Year’s” resolution of 1624/25 obtained above: to the left of Jupiter, on the Virgo side, were Mercury, the Sun and Venus, to the right were Mars, the Moon and Saturn, Fig. 16. That is, when identifying the elder in Fig. 17 with Jupiter, the entire composition takes on the meaning of an additional astronomical indication to the main horoscope.

In the second case, such a transparent correspondence, of course, is no longer observed, however, as it turns out, it does not in the least contradict the “New Year’s” version of the dating obtained above. And even more than that, it not only further confirms it, but also allows us to better understand the logic and way of thinking that guided the author and/or customer of the portrait in question.

Namely, let us ask ourselves the question: what else, besides dividing the planets into two groups, can the fact that they are all depicted the same, small, and, moreover, being in the hands of an old man, personifying (this time) Saturn? It is obvious that the latter holds them all in some kind of subordination (literally, “in his hands”). The question is, what kind of “subordination” can we talk about? The answer is again given by Fig. 16. The fact is that an observer looking at the starry sky on New Year’s Eve in September 1625 saw how Saturn rose approximately two hours before dawn, half an hour later the Moon (in the form of a barely noticeable or even completely indistinguishable crescent), and even after hour - all other planets. That is, figuratively speaking, in these pre-dawn hours, Saturn “reigned” undividedly in the sky, thereby announcing that the coming months would pass under his “control” (as well as all the other planets, equally “subordinate” to him, whose fate, in the near future , ended up “in his hands”, and, of course, with earthly affairs).

And, as is well known, this kind of correlation of the year with the planet “ruling” it was indeed a widespread practice in the era of Kleberger-Dürer, Fig. 23-24.

Rice. 23. Saturn is the ruler of the annual circle. Illustration from a medieval astrological almanac. Allegedly 1491

Medal issued in Nuremberg around 1810. This tradition has been preserved to this day, fig. 25-29.

Rice. 24. Saturn. On the reverse side there is a vestal virgin at the altar and the inscription “Good luck in the new year” (SPENDE NEUES GLUCK IM WECHSEL DES JAHRES).

Rice. 25. “Saturn is the ruler of the year” (JAHRES REGENT SATURN). Medal from the “calendar” series, issued in Austria from 1933 to the present

Rice. 26. Obverse sides of two more Austrian calendar medals (for 1937 and 1972) dedicated to Saturn

Rice. 27. Jupiter and Mars on Austrian calendar medals

Rice. 28. Venus and Mercury on Austrian calendar medals

Rice. 29. Sun and Moon on Austrian calendar medals

Thus, the identification of the elder in Fig. 17 with Saturn also fits perfectly with the solution found above. Except that the reading of the composition turns out to be a little more intricate, and the resulting meaning shifts from a purely astronomical to an allegorical plane.

The latter, however, can be objected to by the fact that Saturn, according to medieval ideas, was considered an ominous, extremely unfavorable planet associated with death and various kinds bad influences. The publication [Saplin] summarizes these views as follows: “Saturn is the fifth astronomical planet... In individual astrology, the following concepts are subordinated to Saturn: partings, obstacles, difficulties, losses, confrontations, endurance, patience, perseverance, solidity, alienation, loneliness, cold , age, difficulty, cruelty, steadfastness, constancy, envy and greed. In world astrology... Saturn is responsible for national disasters, epidemics, famine, etc. ..." And also: “Great misfortune (lat. Infortuna major) is an epithet of the planet Saturn, which was considered the most unfavorable planet, often used in medieval astrology.”

In general, at first glance, it is difficult to imagine a reason that could prompt someone to order their portrait against such a background. And in most cases, this would be quite enough to reject the option of identifying the elder in Fig. 17 precisely with Saturn (thus leaving Jupiter for him as the only candidate). However, in this particular case, such proximity can be very easily explained. The fact is that the picture described above of how the “sinister” Saturn was the first to rise on New Year’s Eve in September 1625 was not entirely complete. To be completely precise, then, as again clearly seen in Fig. 16, “the very first” - according to calculated data, three minutes earlier than Saturn - one of the brightest stars in the sky, Regulus, appeared on the horizon. And after Regulus, it was the turn of the “reigning” Saturn (by the way, the name of this star is also associated with royal power and means, translated from Latin, “little king”).

Regarding Regulus, the publication [Saplin] says this: “Regulus, the Heart of Leo ... is the star α Leo, ... indicates happiness.” That is, from the point of view of the same medieval ideas, by the time of the rise of the “Great Misfortune” = Saturn, his malevolent hypostasis was neutralized by the “happy” Regulus, and, therefore, positive traits came to the fore - “endurance, patience, perseverance, thoroughness, ... steadfastness, constancy.” Strengthened in addition by the “royal” essence of Regulus. Who wouldn't want a set like this?

By the way, it immediately becomes clear why Saturn could be depicted in Fig. 17 in the form of a good-natured old man, without his usual attributes in the form of a scythe and a devoured baby, fig. 22. In this case, they were obviously no longer needed. On the other hand, the author’s train of thought could have been more sophisticated and consisted in the fact that, by depicting the named old man without any characteristic attributes that would clearly indicate Saturn or Jupiter, he thereby provided the viewer, who was quite experienced in such subtleties, with the opportunity correlate it with each of them, in both cases revealing an important part of the overall meaning embedded in the picture.

By the way, Saturn has another aspect, which could also be considered as one of the fragments of the multifaceted symbolism of the picture. Namely, Saturn-Kronos was also associated with the ageless Chronos, that is, Time. And, therefore, the placement of his figure in the portrait, when looking at it from such an angle, could promise a long life for the person depicted, fig. 30-31.

Rice. 30. Saturn-Chronos, wishing good luck in the new year (VERTENTE ANNO - literally: “throughout the whole year”). Medal issued in Augsburg and dating from 1635

Rice. 31. Leopold Habsburg with his son Joseph at the altar of Eternity, opposite them is Chronos-Saturn with a broken scythe and an hourglass thrown to the ground and Fortune with a cornucopia. The reverse side depicts Chronos sitting in the clouds, holding in his hand a snake entwined around the number XVII, biting himself

by the tail (symbol of cyclicity, rebirth, etc.). Augsburg medal, issued in 1700, to commemorate the coming new century

Thus, we see that even the standard interpretation of the symbol in Fig. 4 as denoting the constellation Leo, leads us to a very interesting and symbolically rich result. However, as mentioned above, there is another reading option, according to which this symbol points to a specific star in the sky - Regulus. Let us now consider this possibility.

To be continued...

DURER'S MAGIC SQUARE

The magic square, reproduced by the German artist Albrecht Durer in the engraving “Melancholy”, is known to all researchers of magic squares.

This square is described in detail here. First, I will show the engraving “Melancholy” (Fig. 1) and the magic square that is depicted on it (Fig. 2).

Rice. 1

Rice. 2

Now I will show this square in its usual form (Fig. 3):

|

16 |

3 |

2 |

13 |

|

5 |

10 |

11 |

8 |

|

9 |

6 |

7 |

12 |

|

4 |

15 |

14 |

1 |

Rice. 3

Interestingly, the two middle numbers in the last line of the square (they are highlighted) make up the year the engraving was created - 1514.

It is believed that this square, which so fascinated Albrecht Durer, came to Western Europe from India at the beginning XVIcentury. In India this square was known in Icentury AD. It is believed that magic squares were invented by the Chinese, since the earliest mention of them is found in a Chinese manuscript written 4000-5000 BC. That's how old magic squares are!

Let us now consider all the properties of this amazing square. But we will do this on another square, the group of which includes the Durer square. This means that the Dürer square is obtained from the square that we will now consider by one of the seven main transformations of magic squares, namely a rotation of 180 degrees. All 8 squares that form this group have properties that will now be listed, only in property 8 for some squares the word “row” will be replaced by the word “column” and vice versa.

You can see the main square of this group in Fig. 4.

|

1 |

14 |

15 |

4 |

|

12 |

7 |

6 |

9 |

|

8 |

11 |

10 |

5 |

|

13 |

2 |

3 |

16 |

Rice. 4

Now let's list all the properties of this famous square.

Property 1 . This square is associative, that is, any pair of numbers symmetrically located relative to the center of the square gives a total of 17 = 1+ n 2 .

Property 2. The sum of the numbers located in the corner cells of the square is equal to the magic constant of the square - 34.

Property 3. The sum of the numbers in each corner 2x2 square, as well as in the central 2x2 square, is equal to the magic constant of the square.

Property 4. The magic constant of a square is equal to the sum of the numbers on opposite sides of the two central 2x4 rectangles, namely: 14+15+2+3=34, 12+8+9+5=34.

Property 5. The magic constant of the square is equal to the sum of the numbers in the cells marked by the move of the chess knight, namely: 1+6+16+11=34, 14+9+3+8, 15+5+2+12=34 and 4+10+13 +7=34.

Property 6. The magic constant of a square is equal to the sum of the numbers in the corresponding diagonals of the 2x2 corner squares adjacent to the opposite vertices of the square. For example, in the 2x2 corner squares, which are highlighted in Fig. 4, the sum of the numbers in the first pair of corresponding diagonals: 1+7+10+16=34 (this is understandable, since these numbers are located on the main diagonal of the square itself). The sum of the numbers in the other pair of corresponding diagonals: 14+12+5+3=34.

Property 7. The magic constant of the square is equal to the sum of the numbers in the cells marked by a move similar to the move of a chess knight, but with an elongated letter G. I show these numbers: 1+9+8+16=34, 4+12+5+13=34, 1+2 +15+16=34.4+3+14+13=34.

Property 8. In each row of the square there is a pair of adjacent numbers, the sum of which is 15, and another pair of adjacent numbers, the sum of which is 19. In each column of the square there is a pair of adjacent numbers, the sum of which is 13, and another pair of also adjacent numbers , the sum of which is 21.

Property 9. The sums of the squares of the numbers in the two outer rows are equal to each other. The same can be said about the sums of the squares of the numbers in the two middle rows. See:

1 2 + 14 2 + 15 2 + 4 2 = 13 2 + 2 2 + 3 2 + 16 2 = 438

12 2 + 7 2 + 6 2 + 9 2 = 8 2 + 11 2 + 10 2 + 5 2 = 310

Numbers in the columns of a square have a similar property.

Property 10. If we inscribe a square with vertices in the middle of the sides into the square under consideration (Fig. 5), then:

a) the sum of the numbers located along one pair of opposite sides of an inscribed square is equal to the sum of the numbers located along the other pair of opposite sides, and each of these sums is equal to the magic constant of the square;

b) the sums of squares and sums of cubes of the indicated numbers are equal:

12 2 + 14 2 + 3 2 + 5 2 = 15 2 + 9 2 + 8 2 + 2 2 = 374

12 3 + 14 3 + 3 3 + 5 3 = 15 3 + 9 3 + 8 3 + 2 3 = 4624

Rice. 5

These are the properties of the magic square in Fig. 4.

It should be noted that in an associative square, which is the square in question, you can also perform such transformations as rearranging symmetrical rows and/or columns. For example, in Fig. 6 shows a square obtained from the square in Fig. 4 by rearranging the two middle columns.

|

Share with friends or save for yourself:

|