Investigation of the origin and genesis of the bodies of the Central Sectoral Administration from the 16th to the beginning of the 20th centuries. The history of the formation of collegia as the central body of sectoral management in the Russian Empire of the 18th century

Send your good work in the knowledge base is simple. Use the form below

Students, graduate students, young scientists who use the knowledge base in their studies and work will be very grateful to you.

Posted on http://www.allbest.ru

1. Prerequisites for the formation of colleges

At the head of the management of individual departments and localities of the Moscow state were orders that depended on the boyar duma. Orders, managing individual articles government controlled and farms were arranged in such a way that the departments of individual orders were not strictly delimited. One and the same class of cases, for example, a court, was dealt with in many orders; quite often one order was in charge of a city in one respect, and other orders were in charge of this city in another; one order conducted any one order of affairs in the whole country, and the other order all affairs only in any one locality. The ambassadorial order, for example, conducting diplomatic relations and resolving complex international issues, was in charge at the same time of the outsourcing of the kruzhechny courtyards in Smolensk; and the order of secret affairs, in our opinion - His Majesty's own office - was in charge of the court hunt. Each order was assigned a number of cities from which this order collected revenues in the form of special fees and court fees; these incomes went to the management of the orders themselves. The order usually received all government fees in general from the cities assigned to it, and the order itself sent these fees to the appropriate institutions. And since the number of all orders in the 17th century went over forty, one can imagine what kind of confusion and red tape took place in governing the country. Yes, and in each individual order it was difficult to understand the petitioner or the litigant. The judicial part was not separated from the management; after all, each order was a judge and steward over people subordinate to him and over people who lived in the cities over which this order was in charge. The judges of the orders decided matters the way God wants them to, interpreting the law according to their will. Bribery and hypocrisy prevailed in orders, and Moscow people in the 16th and 18th centuries. considered for themselves a divine punishment, when need drove them to order something - it always cost a lot of money.

The government of Moscow times knew all this well and more than once tried to bring more order to the order system, and did something in this direction, especially to reduce red tape and bribery; but the very basis of the order system remained unchanged - either one and the same side of the state economy turned out to be broken up by departments of separate orders, then the entire economy and management of any one region was concentrated in one order - "ordered" under the jurisdiction of one judge or another. It is interesting that the government papers of those times were never addressed "to such and such an order", but always to the name of the judge of the order: "to such and such." The arbitrariness and imperiousness of the clerks on this basis only strengthened and grew more and more.

Moscow government in the middle of the 17th century. in the fight against the inconveniences of this fragmentation of the control system, it began to pull together homogeneous orders into larger divisions; for this, they either subordinated several others to one order, or put one chief at the head of several homogeneous orders. The ambassadorial order, for example, was in charge in the second half of the 17th century. nine other orders. The order of accounting affairs, established under Tsar Alexei, kept track of the income and expenses of the entire state and collected all the sums of money that remained from the current expenses in all institutions of the entire state; this order, as it were, supervised the financial activities of individual orders and controlled it.

Already during the reign of Peter, the need to collect the entire government of the country and its economy into certain large groups, strictly delimited from one another by the nature of affairs, became apparent. But Peter, like the Moscow government, found it difficult to do this quickly and quickly. The war, with its unexpected turns of happiness for misfortune, luck for failure, hindered, when, behind a quick and unexpected change of events, there was neither time nor opportunity to concentrate, think over the reform plan and quietly and peacefully carry it out steadily and consistently. The war did not wait and imperiously demanded people and money.

In the creation of new institutions, Peter I acted in a very, very old way; busy with the war, he tried to satisfy every need put forward by the events and demands of the war immediately, forming a new department for this. If the new need was not included in the circle of needs managed by the old institutions, and he did not really care if the new institution introduced some disorder in the work of the old ones. In this sometimes hasty, sometimes poorly thought-out change and replacement of some institutions with others, the old orders lost their former character and acquired new features, the circle of the department of individual orders changed. Changed and the very methods of the order management in the direction of greater subordination of judges to the central institution, their greater accountability and greater regulation and the very activity of the order: from the order given by the sovereign, to be in charge of such and such a matter to such and such a person. Orders are becoming more and more government places, each with a certain range of affairs, which are entrusted to the person, and to the institution headed by the executor of the monarch's will responsible before the law, obliged to act not "as God instructs him", but according to the rules and regulations approved by the monarch's authority. But all this was only just outlined and was a desirable, conscious, but not yet realized requirement of life. In fact, there was, perhaps, an even greater confusion of departments than in Moscow time. But all this reshuffling of orders and their departments imperiously indicated one thing - the need to transform the state system on the basis of replacing personal orders with permanent institutions that are in charge of every circle of affairs determined to him, guided by the rules and laws approved by the monarchy.

In 1718 - 1719, the previous state bodies were liquidated, replaced with new ones, more suitable for the young Peter the Great Russia.

The formation of the Senate in 1711 served as a signal for the formation of sectoral management bodies - collegia. According to the plan of Peter I, they were supposed to replace the clumsy system of orders and introduce two new principles into management:

1. Systematic division of departments, since orders often substituted each other, performing the same function, which brought chaos to management. Other functions were not covered at all by any order production.

2. Advisory procedure for resolving cases.

2. Collegiums as the central executive body of Russia

collegial senate russian legality

Already in 1712, an attempt was made to establish a Trade Collegium with the participation of foreigners. Experienced lawyers and officials were recruited in Germany and other European countries to work in Russian government institutions. The Swedish colleges were considered the best in Europe, and they were taken as a model.

At the end of 1717, a system of collegia began to take shape: the Senate appointed presidents and vice-presidents, determined the states and operating procedures. In addition to the leaders, the collegiums included four advisers, four assessors (assessors), a secretary, an actuary, a registrar, and translators and clerks. By a special decree from 1720, it was ordered to start the proceedings of the cases with a "new order".

It turned out to be difficult to "break" the order system overnight, so the one-time abolition had to be abandoned. Orders were either absorbed by the collegiums, or obeyed them (for example, seven orders were included in the Justitz Collegium).

Only by 1718 was the register of the collegia adopted:

1. Foreign affairs (foreign policy).

2. The chamber collegium, or the Collegium of state fees (management government revenues: the appointment of persons in charge of the collection of state revenues, the establishment and cancellation of taxes, the observance of equality between taxes depending on the level of income)

3. Justice Collegium (court).

4. Commerce Board (trade).

5. State office (maintaining government spending and staffing for all departments).

6. Berg-Manufactur-Collegium (industry and mining).

7. Revision board (state control).

8. Military Collegium (Army).

9. Admiralty Board (fleet).

Around 1720, the Justitz Collegium of Livland and Estland Affairs was established, since 1762 it was called the Justitz Collegium of Livland, Estland and Finland Affairs, which dealt with administrative and judicial issues of the annexed Swedish provinces, as well as the activities of Protestant churches throughout the empire.

In 1721, the Patrimony Collegium was established, replacing the Local Order.

In 1722, the Berg-Manufactory-Collegium was divided into the Berg-Collegium and the Manufactory Collegium, and the Little Russian Collegium was established, replacing the Little Russian Order.

In 1726 the College of Economics was established.

The number of collegia was not constant. In 1722, for example, the Revision Board was liquidated, but later restored. To manage Ukraine in 1722, the Little Russian Collegium was created, a little later - the Collegium of Economy (1726), the Justitz Collegium, Livonian, Estonian and Finnish Affairs (circa 1725), and others. the closest associates of Peter I: A.D. Menshikov, G.I. Golovkin, F.M. Apraksin, P.P. Shafirov, Ya. V. Bruce, A.A. Matveev, P.A. Tolstoy, D.M. Golitsyn.

The activities of the collegiums were determined by the General Regulations (1720), which united big number rules and regulations that describe in detail the order of work of the institution. The creation of the collegium system completed the process of centralization and bureaucratization of the state apparatus. A clear distribution of departmental functions, delineation of the spheres of government and competence, uniform standards of activity, concentration of financial management in a single institution - all this significantly distinguished the new apparatus from the order system. With the establishment of a new capital (1713), the central office moved to St. Petersburg. The Senate and the Collegiums were already created there. In 1720, the Chief Magistrate was created in St. Petersburg (as a collegium), who coordinated the work of all magistrates and was an appellate court for them. In 1721, the Charter of the Chief Magistrate was adopted, which regulated the work of magistrates and city police. The sectoral management principle inherent in the collegia was not followed up to the end: judicial and financial functions, in addition to special ones, were assigned to other sectoral collegia (Berg, Manufactur, Kommerts). Whole industries (police, education, medicine, post office) remained outside the sphere of control of the collegia. Colleges were also not included in the sphere of palace administration: the Order of the Grand Palace and the Chancellery of Palace Affairs continued to operate here. This approach to business violated the unity of the college system. The transformation of the government system has changed the nature of the civil service and bureaucracy. With the abolition of the Discharge Order in 1712, lists of Duma officials, 251 stewards, solicitors and other officials were compiled for the last time. In the course of the creation of new administrative bodies, new titles appeared: chancellor, actual privy and privy councilors, advisers, assessors, etc. All positions (civil and courtiers) were equated to officer ranks. The service became professional, and the bureaucracy became a privileged estate.

Meetings of the collegiums were held daily, except for Sundays and holidays... They began at 6 or 8 o'clock in the morning, depending on the season, and lasted 5 hours.

Materials for the collegiums were prepared in the Chancellery of the collegium, from where they were transferred to the general presence of the collegium, where they were discussed and adopted by a majority vote. Issues on which the collegium could not make a decision were transferred to the Senate - the only institution to which the collegiums were subordinate.

Each collegium had a prosecutor, whose duty was to monitor the correct and haphazard decision of cases in the collegium and the execution of decrees, both by the collegium and by structures subordinate to it.

The secretary becomes the central figure in the chancellery. He was responsible for organizing the office work of the collegium, preparing cases for hearing, reporting cases at a meeting of the collegium, conducting reference work on cases, drawing up decisions and monitoring their implementation, keeping the seal of the collegium.

Peter the Great saw the collegial structure of government as a guarantee of the legitimacy of government, greater independence of institutions and greater security for the interests of state power. Peter I considered the collegial form obligatory even in military affairs: "even the best arrangement through councils happens," says one of the articles of the military regulations, "for the sake of this we command, so that, both in the generals and in the regiments, they have advice on all matters in advance" ... Even in the event of a sudden appearance of the enemy, Peter recommends to his generals to send "a verbal consultation, albeit on horseback sitting." The same instructions are contained in the naval charter of Peter I, where the admiral-general is instructed not to dare to repair the main affairs and military undertakings without written consilia, unless he will be accidentally attacked from the enemy.

Of the nine colleges, only two coincided with the old orders in the circle of affairs: the Collegium of Foreign Affairs with the Ambassadorial order and the Revision Collegium with the Accountant; the rest of the collegiums represented the departments of the new composition. In this composition, the territorial element inherent in the old orders disappeared, most of which were in charge of exclusively or mainly known affairs only in a part of the state, in one or several counties. The provincial reform abolished many such orders; the last of them also disappeared in the collegiate reform. Each collegium in the branch of management assigned to it extended its action over the entire space of the state. In general, all the old orders, still living out their days, were either absorbed by the collegiums, or subordinated to them: for example, 7 orders were included in the Justitz Collegium. This was how the departmental division in the center was simplified and rounded; but a number of new offices and chanceries remained, which were either subordinate to the collegiums or constituted special main directorates: so, next to the Military Collegium, there were the Chanceries of the Main Provisions and Artillery and the Main Commissariat, which was in charge of recruiting and equipping the army.

This means that the collegiate reform did not introduce into the departmental routine the simplification and rounding off that the collegia list promises. And Peter could not cope with the hereditary habit of administrative sideways, cages and basements, which the old Moscow state builders liked to introduce into their management, imitating private house-building. However, in the interest of a systematic and even distribution of cases, the original plan of the collegiums was changed during execution. The local order, subordinate to the Justitz Collegium, on burdening it with affairs, separated into an independent patrimonial collegium, the component parts of the Berg and Manufacturing Collegiums were divided into two special collegia, and the Audit Collegium, as a control body, merged with the Senate, the supreme control, and its separation , according to the frank admission of the decree, "it was not considered then committed" as a matter of thoughtlessness. This means that by the end of the reign of all the colleges there were ten.

Another difference between collegia and orders was the deliberative procedure for conducting business. Such an order was not alien to the old order administration: according to the Code, judges or chiefs of orders had to decide cases together with comrades and senior clerks. But the command collegiality was not precisely regulated and died out under the pressure of strong bosses. Peter, who carried out this order in the ministerial consilia, in the district and provincial administration, and then in the Senate, wanted to firmly establish it in all central institutions. Absolute power needs advice to replace the law; "all the best dispensation happens through councils," reads the Military Rule of Peter; It is easier for one person to hide iniquity than for many comrades: let someone give it away. The presence of the college consisted of 11 members, a president, a vice-president, 4 advisers and 4 assessors, to which was added another adviser or assessor from abroad; of the two secretaries of the collegiate chancellery, one was also appointed from among foreigners. Cases were decided by a majority vote of the presence, and for the report to the presence they were distributed between advisers and assessors, of whom each was in charge of the corresponding part of the chancellery, forming a special branch or department of the collegium at the head of it. The introduction of foreigners into the collegiums was intended to place experienced leaders alongside Russian newcomers. For the same purpose, Peter usually appointed a foreigner vice-president to the Russian president. So, in the Military Collegium under the President of Prince Menshikov, the Vice-President - General Veide, in the Chamber Collegium, the President, Prince D.M. Golitsyn, Vice President - Landrat of Revel, Baron Nirot; only at the head of the Gorno-Manufactory Collegium we meet two foreigners, the scientist artilleryman Bruce and the aforementioned Lyuberas.

For a long time, the most important functions remained outside the sphere of control of the collegiums - police, education, medicine, post office. Gradually, however, the collegium system was supplemented by new sectoral bodies. So, the Pharmaceutical Order, which was already in force in the new capital - St. Petersburg, was transformed into the Medical College in 1721, and in 1725 - into the Medical Chancellery.

It is difficult to overestimate the importance of the reform carried out by Peter 1. The collegiums functioned in accordance with uniform standards of activity. Departmental functions were clearly distributed. Localism was finally eliminated. The establishment of these governing bodies was the final stage in the centralization and bureaucratization of the state governing apparatus. However, it is impossible not to clarify that the brilliant idea of the emperor was not fully realized. Thus, the main goal of the reform - the division of functions performed by departments - has not been achieved in relation to some of the Colleges.

Since 1802, the gradual abolition of the Colleges began against the background new system ministries.

Posted on Allbest.ru

...Similar documents

The development of public administration in Kiev and Moscow Rus (IX-XVII centuries). The system of public administration in the Russian Empire (XVIII – early XX centuries). Institutions of state power in the USSR and the reasons for the collapse of the Soviet state.

thesis, added 06/13/2010

Historical preconditions for the formation of the Senate, its structure as a body of state power. Appointment of Yaguzhinsky as the Prosecutor General of the Senate, his powers and competences. Activity of the Senate in 1722-1726 in various spheres of social life.

abstract, added 02/14/2016

Causes of corporal punishment. The main historical stages of the formation of the punishment system in the Russian Empire. The grounds for imposing corporal punishment according to the Code of Laws of 1497 and 1550, according to the Cathedral Code of 1649, according to the Military Articles of 1715.

term paper, added 02/25/2011

The State Council in the system of the highest authorities and administration of the Russian Empire in the 19th - early 20th centuries. Prerequisites and legal foundations of the institution The State Duma... The system of political power in the country. Legislative process in 1906-1917

thesis, added 05/07/2014

The concept of "imperial governance" and the study of the administrative-territorial construction of the empire. Study of the administrative-territorial structure and special characteristics of the Siberian region of the Russian Empire at the end of the XVIII - the first half of the XIX centuries

term paper added on 08/28/2011

Unsuccessful attempts to systematize legislation in the 18th and first quarter of the 19th century. The history of the creation of the complete collection of laws of the Russian Empire (1826-1830), its structure. The reasons, prerequisites and main participants in the creation of a complete collection of laws.

abstract, added 10/22/2012

The development of the state system in the first half of the 19th century. Formation and activity of the State Council as the highest legislative body of Russia, its role in the system of central authorities during the period of the State Duma.

term paper, added 09/08/2009

The policy of perestroika as refracted to the question of the form of state unity. Formation of the state system of Russia. Characteristics of the highest government bodies, sectoral government bodies, local government and the armed forces.

term paper added on 11/24/2010

Search for ways to improve the state administration of the Russian Empire under Alexander I (1801-1825). Historical conditions of public administration reform. Formation of the ministerial system of government. Senate as the highest form of government.

test, added 05/22/2010

The legal system of the Russian Empire. The army of the pre-Petrine Moscow state: the feudal militia and service people. Establishment of a regular army by Emperor Peter I. The Code of Military Regulations as a codified act of military law.

In pre-Moscow Russia, it is extremely difficult to separate state posts from palace posts, whose representatives were in charge of various parts of the prince's household, palace economy ( palace and patrimony management system ). So the prince's personal servant gradually became a statesman, an administrator. There were no permanent departments or special permanent posts at that time.

3rd period ... Until the middle of the 16th century, the palace-patrimonial system of government continued to operate, in which the main place still belonged to the princely court and palace departments - ways ... The routes provided for the special needs of the prince and his entourage. But the change in the nature of the grand-ducal power, the need to manage the significantly increased territory of the state required the creation of a special apparatus. As a result of this, orders - permanent institutions, whose activities extended to the territory of the entire state. Orders as state institutions for a specific industry took shape out of the way, and by the middle of the 16th century, the transition to command and control system .

By the middle of the 17th century, the number of orders reached sixty, and you can clearly define them groups:

- military-administrative - Local, Discharge, Streletsky;

- forensic police - Robber, Zemsky, Sudny;

- financial - Big Parish, Big Treasury, Counting;

- palace - the Great Palace, Gold and Silver Deeds;

- ecclesiastical - Monastic, Patriarchal, Spiritual;

- territorial - Siberian, Kazan.

The orders as state bodies had special premises, certain states, and a complex system of office work.

At the head of each order was a chief, as a rule, a member of the Boyar Duma. Extensive office work, requiring clerical skills, was concentrated in the hands of clerks and clerks.

Large orders were subdivided into tables, and tables were subdivided into povyts.

The orders were rather relative to the branch management. First, they performed not only administrative but also judicial functions; secondly, they could be built not according to the branch, but according to the territorial principle (for example, the Siberian order).

4th period. The ordering system had its own serious limitations:

The competence of orders was not strictly divided;

The activities of the orders were not strictly regulated;

The large number of orders made it difficult to control them.

Peter I "inherited" about 90 orders and the first step was their numerical reduction. But the orders in their previous form could not ensure either the implementation of reforms or the conduct of the Northern War. In addition, the bulk of the boyars, the leaders of the orders, were generally against Peter's innovations.

A radical restructuring of sectoral management took place in 1718-1720, when a system of collegia was created, the activities of which were determined by the General Regulations (1720). The General Regulations established the uniformity of the organizational structure, the order of activities and office work.

Collegiums were the central state institutions subordinate to the Emperor and the Senate. The local apparatus was subordinate to the collegia for various branches of management.

The structure of the collegiums: presence (general meeting) and office.

The following collegia existed , engaged in a certain field of activity:

- military - land army;

- admiralty - the fleet;

- foreign affairs - foreign policy department;

- cameras - government revenues;

- state offices - government spending;

- revision - control over finances;

- justitz – judicial system;

- merchant - trade;

- berg - management of the mining and metallurgical industry;

- manufactories - management of large industry;

- patrimonial - noble land tenure;

- chief magistrate - city management and city government.

Collegiums differed from orders of strictly defined competence and a uniform organizational structure, but the sectoral principle was violated here too (the patrimonial collegium and the Chief Magistrate were built according to the class principle).

Under Catherine II, the collegia were practically abolished, but Paul I was trying to restore these bodies, but already based on the principle of one-man management.

5th period ... At the beginning of the 19th century, collegial management was replaced by ministerial. V 1802 year in Russia, the first eight ministries : military land forces, naval forces, foreign affairs, internal affairs, commerce, finance, public education, justice. An important place in the history of ministries was taken by the General Establishment of Ministries 1811 year, which determined the uniformity of the organization and office work of ministries, the system of relationships between their structural parts, as well as the relationship of ministries with other departments.

The structure of the ministries: a minister with a comrade (assistant), the minister had an office. The working apparatus of the ministry consisted of departments.

Ministers were appointed by the emperor and were responsible only to him. The organization of each ministry was based on the principle of one-man management.

The ministerial system remained in Russia until October 1917.

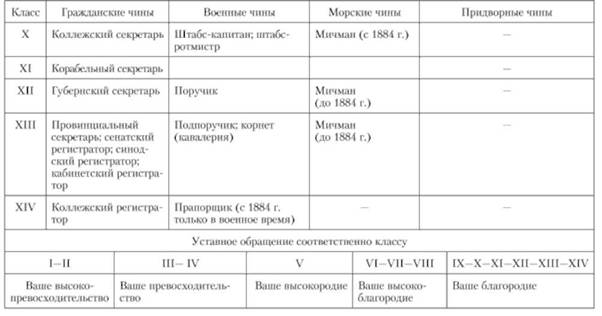

8.2. Reconstruction of the system of higher and central government bodies (Senate, collegiums, government control and supervision bodies). Table of ranks

Peter's state transformations were accompanied by fundamental changes in the sphere top management the state. Against the background of the incipient process of the formation of an absolute monarchy, there is a final decline in the significance of the Boyar Duma. At the turn of the 18th century. it ceases to exist as a permanent institution and is replaced by the first created under it in 1699. Near office, meetings of which, since 1708 have become permanent, began to be called By the Consulate of Ministers. This new institution, which included the heads of the most important state departments, Peter I initially set about conducting all state affairs during his many "absences".

In 1711, a new supreme body of state power and administration was created, which replaced the Boyar Duma - Government Senate. Established before the departure of Peter I for the Prut campaign instead of the abolished Consilia of Ministers, initially as a temporary government body, whose decrees Peter I ordered to execute as unquestioningly as the decisions of the tsar himself, the Senate eventually turned into a permanent supreme administrative and control body in the system of state administration.

The composition of the Senate has undergone a number of changes since its inception. At first, it consisted of noble persons appointed by the sovereign, who were entrusted with the administration of the state during the absence of the king. Later, from 1718, when the Senate became a permanent institution, its composition changed, all the presidents created by that time began to sit in it. collegiums (central government bodies that replaced the Moscow orders). However, the inconveniences of this state of affairs soon came to light. As the highest administrative body in the state, the Senate was supposed to control the activities of the collegia, but in reality it could not do this, since it included the presidents of the same collegia ("now being in them, as they can judge themselves"). By a decree of January 22, 1722, the Senate was reformed. The presidents of the collegia were removed from the Senate, they were replaced by specially appointed, independent persons in relation to the collegiums (the right to sit in the Senate was reserved only for the presidents of the Military Collegium, the Collegium of Foreign Affairs and, for a time, the Berg Collegium).

The Senate attended three times a week (Monday, Wednesday, Friday). For the proceedings of the Senate, there was an office, initially headed (before the establishment of the position of the Prosecutor General) chief secretary (the titles of positions and titles were for the most part German). Helped him executor, keeping order in the building, sending and registering the decrees of the Senate. At the Senate Chancellery there were notary actuary(custodian of documents), registrar and archivist. The same posts were in the collegia, they were determined by one "General Regulations".

The Senate also included: Attorney-General, General-Recket Master, Master of Heralds and Ober-fiscal. The establishment of these posts was of fundamental importance for Peter I. Thus, the General-Reketmeister (1720) had to accept all complaints about the wrong decision of affairs in the collegiums and the Chancellery of the Senate and, in accordance with them, either force the state institutions subordinate to the Senate to a fair decision of cases, or report on complaints to the Senate. It was also the duty of the General-Reketmeister to strictly monitor that complaints against the lower governing bodies did not go directly to the Senate, bypassing the collegiums. The main duties of the king of arms (1722) were the collection of data and the compilation of personal service records of the nobility, the entry into the genealogy books of the nobility of persons of lower ranks who rose to the rank of non-commissioned officer. He also had to make sure that more than 1/3 of each noble family was not in the civil service (so as not to run out of land).

In its main activity, the Government Senate carried out practically the same functions that at one time belonged to the Boyar Duma. As the highest administrative body in the state, he was in charge of all branches of government, supervised the government apparatus and officials at all levels, and performed legislative and executive functions. At the end of the reign of Peter I, the Senate was also assigned judicial functions, making it the highest court in the state.

At the same time, the position of the Senate in the system of public administration was significantly different from the role that the Boyar Duma played in the Moscow state. Unlike the Boyar Duma, which was an estate body and shared power with the tsar, the Senate was originally created as a purely bureaucratic institution, all members of which were appointed personally by Peter I and were under his control. Without admitting the very idea of the independence of the Senate, Peter I tried to control its activities in every possible way. Initially, the Auditor General looked after the Senate (1715), later for this, the staff officers of the Guards (1721) were appointed, who were on duty in the Senate and monitored both the acceleration of the passage of affairs in the Senate Chancellery and the observance of order in the meetings of this supreme state body.

In 1722 a special position was established attorney general The Senate, called upon, according to the plan of Peter I, to provide communication between the supreme power and the central government (to be the "eye of the sovereign") and to exercise control over the activities of the Senate. Not trusting the senators and not hoping for their conscientiousness in resolving matters of state importance, Peter I by this act, in fact, established a kind of double control ("control over control"), placing the Senate, which was the highest body of control over the administration, in the position of a supervised institution ... The Prosecutor General personally reported to the Tsar on matters in the Senate, conveyed the will of the supreme power to the Senate, could stop the Senate's decision, and the Senate Chancellery was subordinate to him. All decrees of the Senate received force only with his consent, he also monitored the implementation of these decrees. All this not only put the Attorney General over the Senate, but also made him, in the opinion of many, the first person in the state after the monarch.

In the light of the above, the allegations of the empowerment of the Senate with legislative functions are controversial. Although initially the Senate had something to do with lawmaking (it issued the so-called "general definitions" equated to laws), unlike the previous Boyar Duma, it was not a legislative body. Peter I could not allow the existence of an institution next to him, endowed with the right to make laws, since he considered himself the only source of legislative power in the state. Becoming emperor (1721) and reorganizing the Senate (1722), he deprived him of any opportunity to engage in legislative activity.

Perhaps one of the most important innovations of the Petrine administrative reform was the creation in Russia of an effective systems of state supervision and control, designed to control the activities of the administration and to safeguard the state interests. Under Peter I, a new one begins to form for Russia institute of the prosecutor's office. The highest control functions belonged to the Attorney General of the Senate. He was subordinate to other agents of government oversight: chief prosecutors and prosecutors at the collegia and in the provinces. In parallel with this, a ramified system of secret supervision over the activities of the state administration was created in the form of posts established at all levels of management. fiscal.

The introduction of the institution of fiscal was a reflection of the police nature of the Petrine system of government, became the personification of the government's distrust of the state administration. Already in 1711, the position was introduced at the Senate ober-fiscada. In 1714, a special decree was issued on the distribution of fiscal to different levels of government. The Senate consisted of an ober-fiscal and four fiscal, under provincial governments - four fiscal led by a provincial fiscal, each city - one or two fiscal, each collegium also established fiscal positions. Their duty was to secretly find out about all the violations and abuses of officials, about bribes, theft of the treasury and inform the chief fiscal. Denunciation was encouraged and even rewarded financially (part of the fine imposed on the violator or bribe-taker went to the fiscal who reported him). Thus, the denunciation system was raised to the rank public policy... Even in the Church, a system of fiscal (inquisitors) was introduced, and the priests, by a special royal decree, were obliged to violate the secrecy of confession and report to the authorities on the confessed if their confession contained one or another "sedition" that threatened the interests of the state.

It has already been said above that the modernization of the state apparatus carried out by Peter I was not distinguished by a systematic and strict sequence. However, upon closer examination of the Peter's reformation, it is easy to see that with all this two tasks remained for Peter I always priority and indisputable. These tasks were: 1) unification government bodies and the entire system of administration; 2) conducting through the entire administration collegial beginning, which, together with the system of explicit (prosecutorial) and secret (fiscal system) control, should, according to the king, ensure the rule of law in government.

In 1718-1720. new bodies were established central administration named collegiums. They replaced the old orders and were built according to Western European models. The Swedish collegiate device was taken as a basis, which Peter I considered the most successful and suitable for the conditions of Russia. The creation of the collegiums was preceded by a lot of work on the study of European bureaucratic forms and clerical practice. Experienced practitioners, who are well acquainted with clerical work and the peculiarities of collegial organization ("in the right of the skilful"), were specially discharged from abroad to organize new institutions. Swedish prisoners were also invited. As a rule, each collegium from foreigners appointed one adviser or assessor, one secretary and one schreiber (clerk). At the same time, Peter I tried to appoint only Russian people to the highest leading posts in the collegiums (presidents of the collegiums); foreigners usually did not rise higher than vice-presidents.

Establishing the collegiums. Peter I proceeds from the idea that “conciliar government in a monarchical state is the best. The advantage of the collegial system was seen in a more efficient and at the same time objective solution of matters (“ one head is good, two is better). It was also believed that the collegial structure of state institutions would significantly limit the arbitrariness of high officials and, no less important, get rid of one of the main defects of the former order system - the widespread spread of bribery and embezzlement.

The collegium began its activity in 1719. In total, 12 collegiums were created: Foreign Affairs, Military, Admiralty (naval), State Offices (Department of State Expenditures), Chamber Collegium (Department of State Revenues), Revision Board (exercising financial control) , Justitz Collegium, Manufacturing Collegium (industry), Berg Collegium (mining), Komerts Collegium (trade), Patrimony and Spiritual Collegium. Formally, the collegia were subordinate to the Senate, which controlled the activities of the collegia and sent them its decrees. With the help of prosecutors appointed to the collegia, who were subordinate to the Attorney General of the Senate, the Senate supervised the activities of the presidents of the collegia. However, in reality, there was no clear uniformity in the subordination here: not all collegia were equally subordinate to the Senate (the Military and Admiralty collegiums had much greater independence in comparison with other collegia).

Each collegium drew up its own regulations that determined the scope of its actions and responsibilities. The decree of April 28, 1718 ordered to compose regulations for all collegiums on the basis of the Swedish charter, applying the latter to the "position of the Russian state." Since 1720, the "General Regulations" were also introduced, which consisted of 156 chapters and was common to all collegia.

Similar to the orders of the 17th century. the collegiums consisted of general presence and office. The presence consisted of a president, a vice president, four (sometimes five) advisers, and four assessors (a total of no more than 13 people). The president of the college was appointed by the king (later by the emperor), the vice-president - by the Senate, followed by confirmation by the emperor. The collegiate chancellery was headed by a secretary, who was subordinate to a notary or a record clerk, an actuary, a translator and a registrar. All other clerical officials were called clerks and copyists and were directly involved in the production of cases on the appointment of a secretary. The presence of the college gathered in a specially designated room, decorated with carpets and good furniture (gathering in a private house is prohibited). No one could enter the "chamber" without a report during the meeting. Outside conversations in the presence were also prohibited. The meetings were held every day (excluding holidays and Sundays) from 6 pm or 8 am. All issues discussed at the meeting of the presence were decided by a majority vote. At the same time, the rule was strictly observed, according to which, when discussing an issue, opinions were expressed by all members of the presence in turn, starting with the younger ones. The protocol and the decision were signed by all those present.

The introduction of the collegial system greatly simplified (from the point of view of eliminating the previous confusion in the order management system) and made it more efficient state machine management, gave him some uniformity, clearer competences. In contrast to the order system, which was based on the territorial-sectoral principle of management, the collegia were built according to the functional principle and could not interfere with the activities of other collegia. However, it cannot be said that Peter I managed to completely get rid of the shortcomings of the previous management system. It was not possible not only to build a strict hierarchy of levels of government (Senate - collegiums - provinces), but also to avoid confusion of the collegial principle with the personal, which was the basis of the old command system.

As in the orders, in the newly created colleges the last word often it remained with the authorities, in this case the presidents of the collegia, who, together with the prosecutors assigned to the collegia to control their activities, by their intervention, replaced the collegial principle of decision-making by one-man. In addition, the collegia did not replace all the old orders. Next to them, there were still order institutions, called either offices, or, as before, orders (Secret Office. Medical Office, Preobrazhensky Prikaz, Siberian Prikaz).

In the course of Peter's state reforms, the final form of the absolute monarchy in Russia took place. In 1721, Peter I took the title of emperor. In a number of official documents - the Military Regulations, the Spiritual Regulations and others - the autocratic nature of the monarch's power was legally enshrined, which, as the Spiritual Regulations said, "God himself commands for conscience."

In the general mainstream of the final stage of the process of the formation of the absolute monarchy in Russia, there was also the reform of church government, the result of which was the abolition of the patriarchate and the final subordination of the Church to the state. February 14, 1721 was established Holy Governing Synod, replacing the patriarchal power and arranged according to the general type of organization of colleges. The Spiritual Regulations, prepared for this purpose by Feofan Prokopovich (one of the main ideologues of the Petrine reformation) and edited by the tsar himself, directly pointed out the imperfection of the sole rule of the patriarch, as well as those political inconveniences that resulted from the exaggeration of the place and role of the patriarchal power in the affairs of the state. ... The collegial form of church administration was recommended as the most convenient. The Synod formed on this basis consisted of 12 members appointed by the king from representatives of the clergy, including the highest (archbishops, bishops, abbots, archimandrites, archpriests). All of them, upon taking office, had to take an oath of allegiance to the emperor. At the head of the Synod was chief prosecutor (1722), appointed to supervise his activities and personally subordinate to the emperor. The positions in the Synod were the same as in the collegia: president, two vice-presidents, four advisers and four assessors.

Under Peter I, in the course of the reform of the state apparatus, accompanied by the institutionalization of management, the spread and active implementation of the principles of Western European cameralism, the old traditional model of public administration was basically rebuilt, in the place of which a modern rational model of state administration begins to take shape.

The overall result of the administrative reform was the approval of a new system for organizing the civil service and the transition, within the framework of the emerging rational bureaucracy, to new principles of completing the apparatus government agencies. A special role in this process was called upon to play the g. Introduced by Peter I on February 22, 1722. Table of Ranks, which is considered today to be the first law on public service in Russia, which determined the procedure for the passage of service by officials and consolidated the legal status of persons who were in public service. Its main significance consisted in the fact that it fundamentally broke with the previous traditions of management embodied in the system of parochialism, and established a new principle of appointment to public office - the principle of serviceability. At the same time, the central government sought to place officials under strict state control. For this purpose, a fixed size of the salary of government officials was established in accordance with the position held, the use of official position for the purpose of obtaining personal gain ("bribery" and "bribery") was severely punished.

The introduction of the "Table of Ranks" was closely related to the new personnel policy in the state. Under Peter I, the nobility (from that time called the gentry) became the main class, from which cadres were drawn for the state civil service, which was isolated from military service. According to the "Table of Ranks," the nobles, as the most educated stratum of Russian society, received the preferential right to civil service. Geli, a pedagogue was appointed to a public office, he acquired the rights of the nobility.

Peter I severely demanded that the nobles serve the civil service as their direct estate duty: all the nobles had to serve either in the army, or in the navy, or in government institutions. The entire mass of service nobles was placed under the direct subordination of the Senate (previously they were under the jurisdiction of the Discharge Order), which carried out all appointments in the civil service (with the exception of the first five upper classes). The accounting of fit for service nobles and staffing of the civil service were entrusted to the Senate king of arms, who was supposed to keep the lists of nobles and provide the Senate with the necessary information on candidates for vacant public positions, strictly monitor that nobles did not evade service, and, if possible, organize professional training for officials.

With the introduction of the "Table of Ranks" (Table 8.1), the previous division of the nobility into class groups (Moscow noblemen, policemen, boyar children) was abolished, and a ladder of service class ranks, directly related to the passage of military or civilian service. The "Table of Ranks" established 14 such class ranks (ranks), giving the right to occupy one or another class position. The occupation of class positions corresponding to ranks from 14 to 5 took place in the order of promotion (career growth), starting from the lowest rank. The highest ranks (from 1 to 5) were awarded by the will of the emperor for special services to the Fatherland and the monarch. In addition to the positions of the civil service, the status of which was determined by the "Table of Ranks", there was a huge army of lower clerical employees who make up the so-called.

Table 8.1. Petrovskaya "Table of Ranks"

A feature of the Petrine Table of Ranks, which distinguished it from similar acts of European states, was that, firstly, it closely linked the assignment of ranks with the specific service of certain persons (for persons not in the civil service, class ranks were not were provided), secondly, the basis for promotion was not the principle of merit, but seniority principle(it was necessary to start service from the lowest rank and serve in each of the ranks for a set number of years). In a similar way, Peter I intended to simultaneously solve two problems: to force the nobles to enter public service; to attract people from other estates to the public service, for whom being in the public service meant the only opportunity to receive the nobility - first personal, and in the long term and hereditary (upon reaching the VIII class rank).

Governing Senate in the Russian Empire - the highest state body subordinate to the emperor. Established by Peter the Great on February 22 (March 2) 1711 as the supreme body of state power and legislation.

From the beginning of the 19th century, he carried out supervisory functions over the activities of state institutions; since 1864 - the highest cassation instance.

During his constant absences, which often prevented him from dealing with the current affairs of management, he repeatedly (in 1706, 1707 and 1710) handed cases over to several selected persons, from whom he demanded that they, without asking him for any explanations, do things like give them an answer on the day of judgment. At first, such powers were in the nature of a temporary personal assignment; but in 1711 they were entrusted to the institution created on February 22nd, which received the name Governing Senate.

The Senate founded by Peter did not represent the slightest resemblance to foreign institutions of the same name (Sweden, Poland) and met the peculiar conditions of the Russian state life of that time. The degree of power granted to the Senate was determined by the fact that the Senate was established in place of his own royal majesty. In a decree on March 2, 1711, Peter says: "We have determined the governing Senate, to which everyone and their decrees may be obedient, as to ourselves, under severe punishment, or even death, depending on our fault."

In the absence at that time of division of cases into judicial, administrative and legislative, and in view of the fact that even the most insignificant affairs of the current administration were constantly raised for the permission of the monarch, who was replaced by the Senate, the circle of the Senate's department could not get any definite outlines. In a decree issued a few days after the establishment of the Senate ( Complete Collection Laws No. 2330), Peter determines what, after his departure, the Senate should do: “The court has unhypocritical, unnecessary expenses set aside; collect as much money as possible; to gather the young nobles; fix bills; and try to give the salt at the mercy; bargaining Chinese and Persian to multiply; to caress the Armenians; perpetrate the fiscal. " This, obviously, is not an exhaustive list of the department's subjects, but an instruction on what to focus on. “Now everything is in your hands,” Peter wrote to the Senate.

The Senate was not a political institution, in any way limiting or restricting the power of Peter; he acted only at the behest of the king and was responsible to him for everything; the decree on March 2, 1711 says: "And if this Senate through its now brought before God a promise unrighteous, what to do ... and then we will be destined, and the guilty will be severely punished".

The practical, business significance of the Senate was determined not only by the degree and breadth of the powers granted to it, but also by the system of those institutions that were grouped around it and made one whole with it. These were, first of all, the commissars, two from each province, "for demand and the adoption of decrees." Through these commissars, appointed by the governors, direct relations between the Senate and the provinces were created, where Peter in 1710, in the interests of the economic structure of his army, transferred a significant part of the affairs that were previously carried out in orders. The commissars not only adopted decrees, but also monitored their implementation, provided the Senate with the necessary information, and carried out its instructions in the field. Subsequently, with the establishment of collegia, the importance of the commissioners decreases: collegia become an intermediary link between the Senate and the provinces. Simultaneously with the establishment of the Senate, Peter commanded "instead of ordering the discharge, there should be a discharge table at the Senate." Thus, the Senate went to "writing to ranks", that is, appointment to all military and civilian positions, management of the entire service class, keeping him lists, conducting reviews and monitoring non-concealment from service. In 1721-1722, the discharge table was first transformed into a collapsible chancellery, which was also attached to the Senate, and on February 5, 1722, a herald master was appointed at the Senate, who was in charge of the service class through the herald's office.

A few days after the establishment of the Senate, on March 5, 1711, the position of fiscal was created, their duty was to "secretly supervise all affairs", visiting and denouncing "all sorts of crimes, bribes, theft of the treasury, etc., as well as other silent deeds. , those who do not have a petition about themselves. "

Under the Senate, there was a chief fiscal (later general fiscal) with four assistants, in each province - a provincial fiscal with three assistants, in every city - one or two city fiscal. Despite the abuses with which the existence of such secret spies and informers is inextricably linked (until 1714, they were not punished even for false denunciation), the fiscal undoubtedly brought a certain amount of benefit, being an instrument of supervision over local institutions.

When Peter's constant absences, which caused the establishment of the Senate, ceased, the question of closing it does not arise. With decreasing orders, the Senate becomes the place where all the most important cases of administration, court and current legislation are carried out. The values of the Senate were not undermined by the establishment (1718-1720) of the colleges, despite the fact that their regulations, borrowed from Sweden, where the colleges were the highest institutions in the state, did not determine the relationship of the colleges to the Senate, which foreign reform leaders - Fick and others - assumed , apparently, abolish. On the contrary, with the establishment of the collegia, where the mass of current small matters went, the importance of the Senate only increased. By the decree of 1718 "on the position of the Senate" all the presidents of the collegiums by their very rank were made senators. This order did not last long; the slowness of the Senate's clerical work forced Peter to admit (in a decree on January 12, 1722) that the presidents of the collegia did not have enough time to carry, moreover, the "incessant" labors of the senator. In addition, Peter found that the Senate, as the highest authority over the collegia, cannot consist of persons who sit in the collegia. Contemporaries also point out that the presidents of the collegiums, being such dignitaries as the then senators, completely suppressed their "advisers" and thereby destroyed any practical significance of collegial decision of affairs. Indeed, the newly appointed presidents, instead of the previous ones who remained senators, were incomparably less noble people. On May 30, 1720, Peter ordered to create a noble person for the sake of admission to the Senate; the duties of this position were determined on February 5, 1722 detailed instructions, and the "person" she clothed was called the reketmaster. Reketmeister very soon acquired great importance as a body overseeing office work in the collegiums and the course of justice.

Of all the institutions that ever belonged to the Senate, the institution of the prosecutor's office, which also appeared in 1722, was of the most practical importance. Peter did not come to the establishment of the prosecutor's office immediately. His dissatisfaction with the Senate was reflected in the establishment in 1715 (November 27) of the post of auditor general, or overseer of decrees. Vasily Zotov, who was appointed to this position, turned out to be too weak to influence the senators and prevent their voluntary and involuntary violations of decrees. In 1718 he was assigned to the tax audit, and his position was abolished by itself.

Constant quarrels between senators again forced Peter to entrust someone with supervision over the course of the Senate meetings. The person chosen (February 13, 1720) by him - Anisim Shchukin - turned out to be unsuitable for these duties; being at the same time the chief secretary of the Senate, Shchukin himself was subordinate to him. A few days after the death of Shchukin (January 28, 1721), Peter entrusted the supervision of the deanery of the Senate meetings to the guard staff officers who were changing every month. On January 12, 1722, they were replaced by the prosecutor's office in the form of a complex and orderly system of supervision not only over the Senate, but also over all central and local administrative and judicial institutions. The Prosecutor General's Office was headed by the Prosecutor General as the head of the Senate Chancellery and as a body overseeing the Senate presence from the point of view of not only deanery during meetings, but also the compliance of Senate decisions with the Code and decrees. The assistant prosecutor general in the Senate was the chief prosecutor. Being in direct relations with the sovereign, the attorney general brought the Senate closer to the supreme power; at the same time, his supervision to a large extent streamlined the proceedings both in the very presence of the Senate and in his chancellery, and greatly raised its business significance. On the other hand, however, the Attorney General stripped the Senate presence of his former independence; being in many cases equal to the entire Senate by law, the attorney general in fact often prevailed over him.

In the last years of Peter's reign, when, at the end of the Northern War, he began to pay more attention to the affairs of internal government, the extraordinary powers vested in the Senate lost their meaning. The decline in the power of the Senate is reflected mainly in the area of legislation. In the first decade of its existence, the Senate, in the region civil law restrained by the authority of the Cathedral Code of 1649, in the field of administrative law he enjoyed very wide legislative power. On November 19, 1721, Peter ordered the Senate not to repair any determination of the general without signing his hand. In April 1714, it was forbidden to bring complaints to the sovereign about unjust decisions of the Senate, which introduced a completely new beginning for Russia; until that time the sovereign could complain about every institution. This prohibition was repeated in the decree on December 22, 1718, and the death penalty was established for bringing a complaint to the Senate.

From 1711 to 1714, the seat of the Senate was Moscow, but sometimes for a time, as a whole or in the person of several senators, he moved to Petersburg, which since 1714 became his permanent seat; Since then, the Senate moved to Moscow only temporarily, in the case of Peter's trips there for a long time. A part of the Senate Chancellery remained in Moscow under the name "Chancellery of the Senate Board." On January 19, 1722, offices from each collegium were established in Moscow, and a senate office was set up above them, consisting of one senator, who changed annually, and two assessors. The purpose of these offices was to facilitate relations between the Senate and the collegiums with Moscow and provincial institutions and the production of small current affairs.

Initially, the Senate consisted of nine people: Count Ivan Alekseevich Musin-Pushkin, Boyar Tikhon Nikitich Streshnev, Prince Pyotr Alekseevich Golitsyn, Prince Mikhail Vladimirovich Dolgorukov, Prince Grigory Andreevich Plemyannikov, Prince Grigory Ivanovich Volkonsky, General Kriegsalmeister Samarist General Vasily Andreevich Apukhtin and Nazariy Petrovich Melnitsky. Anisim Shchukin was appointed Chief Secretary [

25. Collegiate management system in Russia: history of creation and principle of operation. (Like it was during the reign of Peter 1)

THE COLLEGES- the central bodies of sectoral management in the Russian Empire, formed in the Petrine era to replace the system of orders that had lost its significance. Colleges existed until 1802, when they were replaced by ministries.

Collegiate management system- the system of public administration, in which executive and administrative power is exercised collectively in specially created sectoral bodies - collegia.

The main feature of the collegial management system is that decisions are made in a collegial way - by the presence of the collegium. The presence of the college included: the president (appointed by the Senate taking into account the opinion of the emperor), the vice president (appointed by the Senate), four advisers, four assessors (assessors), a secretary, an office clerk (actuary), a registrar, a translator, and a clerk.

Under Peter I, the complex and confusing system of orders was replaced by a new, clear system of collegia. Despite the fact that the distinction between judicial and administrative powers was still absent, in fact, it was the collegia that became the first bodies of sectoral management. Each of the collegiums had to be in charge of a clearly defined branch of management: foreign affairs, maritime affairs, government revenues, etc.

In their activities, the collegiums were guided by the "General Regulations" approved by Peter I on February 28, 1720.

Reasons for the formation of colleges

In 1718 - 1719, the previous state bodies were liquidated, replaced with new ones, more suitable for the young Peter the Great Russia.

The formation of the Senate in 1711 served as a signal for the formation of sectoral management bodies - collegia. According to the plan of Peter I, they were supposed to replace the clumsy system of orders and introduce two new principles into management:

Systematic division of departments (orders often substituted each other, performing the same function, which introduced chaos in management. Other functions were and were not at all covered by any order production).

Advisory procedure for resolving cases.

The growing tasks of the state, the development of industry, trade, and the aggravation of class contradictions led to organizational restructuring of the central state bodies and a change in their powers. To reduce the cost of maintaining the state apparatus, some collegia united. For example, the Commerce Collegium, which was in charge of the parish, and the State Collegium - the expenditure of funds, merged into one. In 1727 the Collegium of Manufacture was merged with the Commerce Collegium. In 1731 the Berg Collegium was destroyed, which damaged the development of mining plants. Some of the colleges were restored or re-created in the 40-60s. Many departments and offices have undergone changes. The instability of the elements of the state mechanism at the level of central government became more and more apparent.

Relative stability was maintained in the security organs of the regime, as well as in the institutions that ensured the collection of taxes and taxes to the state budget. Search and court institutions were given great attention by the government. Police establishments remained permanently operating. In 1729, the Chancellery of Confiscation was created, which ensured confiscation actions based on court verdicts. A year later, the Due Order was formed, which ensured police actions with debtors, bankrupts.

In the 40s. some collegia were restored as independent central institutions, previously united on related issues into one management structure. The Berg and Manufacturing Collegiums, as well as the Chief Magistrate, became independent. To check the noble rights to land, to find out the "true gentry", the "Instruction on General Land Surveying" was developed, which was guided by the administrative apparatus. During the period under review in the history of Russia, such administrative institutions as the Siberian Order, the Printing Office, the Yamskaya Chancellery with offices, the Raskolnichy Office, the Salt Office, and others were actively operating.

It took shape by the middle of the 18th century. the collegial management system was variegated. Its central government institutions (collegia, orders, offices) differed in structure and powers. The college system was in crisis. But at the same time, new principles of their organization and actions were manifested in the central governing bodies.

The activities of the collegiums were determined General regulations, approved by Peter I on February 28, 1720 (lost its meaning with the publication of the Code of Laws of the Russian Empire).

The full name of this regulation: "General regulations or charter, according to which the state collegia, as well as all the clerks belonging to them, not only in external and internal institutions, but also in the administration of their rank, have to act in a subject".

The General Regulations introduced a system of office work, which was named "collegiate" after the name of a new type of institution - collegia. The dominant importance in these institutions has received collegial decision making the presence of the board. Peter I paid special attention to this form of decision-making, noting that “ all the best dispensation through advice happens"(Chapter 2 of the General Regulations" On the advantage of collegiums ").

The work of the collegia

The Senate participated in the appointment of the presidents and vice-presidents of the collegia (when appointing the president, the opinion of the tsar (emperor) was taken into account). In addition to them, the new bodies included: four advisers, four assessors (assessors), a secretary, an actuary (a clerical officer registering acts or their constituent), a registrar, a translator, a clerk.

The president was the first person in the collegium, but he could not decide anything without the consent of the members of the collegium. Vice President replaced the president during his absence; usually assisted him in the performance of his duties as chairman of the board.

Meetings of the collegiums were held every day, except for Sundays and holidays. They began at 6 or 8 o'clock in the morning, depending on the season, and lasted 5 hours.

Materials for the collegiums were prepared in Collegium Chanceries from where they were transmitted to General presence of the board where were discussed and adopted the majority votes. Issues on which the collegium could not make a decision were transferred to the Senate - the only institution to which the collegiums were subordinate.

Each collegium had a prosecutor, whose duty was to monitor the correct and haphazard decision of cases in the collegium and the execution of decrees by both the collegium and its subordinate structures.

The central figure of the chancellery is Secretary... He was responsible for organizing the office work of the collegium, preparing cases for the hearing, reporting cases at a meeting of the collegium, conducting reference work on cases, drawing up decisions and monitoring their execution, keeping the seal of the collegium.

The value of the collegia

The creation of the collegium system completed the process of centralization and bureaucratization of the state apparatus. A clear distribution of departmental functions, uniform standards of activity (according to the General Regulations) - all this significantly distinguished the new apparatus from the order system.

In addition, the creation of colleges dealt the final blow to the system of parochialism, abolished back in 1682, but which took place unofficially.

Disadvantages of collegiums

The grandiose plan of Peter I to delimit departmental functions and give each official a clear plan of action was not fully implemented. Often the collegiums substituted for each other (as once orders). So, for example, Berg, Manufactur and Commerce Collegiums could perform the same function.

For a long time, the most important functions remained outside the sphere of control of the collegiums - police, education, medicine, post office. Gradually, however, the collegium system was supplemented by new sectoral bodies. So, the Pharmaceutical Order, which was already in force in the new capital - St. Petersburg, was transformed into the Medical College in 1721, and in 1725 - into the Medical Chancellery.

26. Reforms of local government in Russia in the first quarter of the XVIII century.

Local government at the beginning of the 18th century. was carried out on the basis of the old model: the provincial administration and the system of regional orders. In the process of Peter's transformations, changes began to be made in this system. In 1702, the institute of voivodship comrades, elected from the local nobility, was introduced. In 1705. this order becomes mandatory and ubiquitous, which should have strengthened control over the old administration.

In 1708, a new territorial division of the state was introduced: eight provinces were established, according to which all counties and cities were assigned. In 1713 - 1714 the number of provinces increased to eleven.

A governor or a governor-general (Petersburg and Azov provinces) was placed at the head of the province, who united in their hands all the administrative, judicial and military power. Four branch management assistants were subordinate to them.

In the course of the reform (by 1715), a three-tier system of local government and administration was formed: county - province - province. The province was headed by the chief commandant, to whom the commandants of the counties were subordinate. The control of the lower administrative levels was assisted by the Landrat Commissions, elected from the local nobility.

The second regional reform was carried out in 1719. Its essence was as follows: eleven provinces were divided into forty-five provinces. These units were also headed by governors, vice-governors or voivods. Provinces were divided into districts. The provincial administration was directly subordinate to the collegia. Four Collegia (Kamer, State Office of Justice, Votchinnaya) had their own branched apparatus of chamberlains, commandants, and treasurers in the localities. An important role was played by such local offices as chamberlain's affairs (distribution and collection of taxes) and rent-treasury (reception and spending of money according to the orders of the governor and chamberlains). In 1719, the governors were entrusted with the supervision of "the preservation of the state interest", the adoption of state security measures, the strengthening of the church, the defense of the territory, supervision of the local administration, trading, crafts and the observance of the royal decrees.

In 1718 - 1720 the reorganization of the bodies of city self-government, created in 1699 together with the Town Hall - zemstvo huts and zemstvo mayors took place. New bodies were created - magistrates, subordinate to the governors. General management was carried out by the Chief Magistrate. The management system has become more bureaucratic and centralized. In 1727 the magistrates were transformed into town halls.

Local government reform 1708 - 1710 destroyed the old principle of appointing to office for the "sovereign grant" and turned all officials of local government into officials of an absolute monarchy, guided not by private orders given from orders, but by national laws and regulations.

Wishing to place the activities of the governors under the control of the local nobility, the government, by a decree of 1713, established 8 - 12 landrats (advisers) for each governor, proposing to elect them "by all the nobles at their hands." The governor had to decide all matters jointly with this collegium of nobility, in which he could speak "not like a ruler, but like a president" with two votes ( PSZ, vol. V, No. 2762.).

As well as the collegia under the governors in the first years of the 18th century, the Landrat collegiums were practically not created. The bulk of the nobles were already in the state, serving in the army, in the navy, in the central and local apparatus, and there was no one to elect landraces for the counties. The Landrats appointed by the Senate became officials who carried out certain orders of the governors.

Already in 1714, the landrats were sent to the counties for the production of a new house-to-house census, on the basis of which, in 1715, for the greater convenience of collecting taxes and manning the army, "shares" were created - new administrative-territorial units that replaced counties, which were formed historically and no longer corresponded to the actual tasks of local government. Geographically, the shares did not coincide with the counties, some were larger than them, others were smaller. The division into shares was based on the tax district equal to 5536 tax households. In almost every share, the number of courtyards of taxpayers ranged from 5000 to 8000. Each share was headed by the Landrat, who was in charge of the population of the share in administrative, police, financial and judicial relations. From an adviser to the collegium under the governor, by law, in reality, the Landrat turned into a provincial administrative official, the heir to the governor-commandant.

The provincial (commandant's) chancellery was respectively replaced by the Landrat's chancellery.

The first reform of the local apparatus 1708 - 1715 somewhat streamlined the government apparatus, destroying the departmental diversity and the principles of territorial division and administration. However, this reform has not yet eliminated diversity in local government. The bureaucratic chain of government agencies and officials created by her was still very weak and rare in order to fetter any manifestations of discontent of the masses with feudal and tax oppression, arbitrariness of officials and recruitment.

The establishment of the collegium and the proposed new poll taxation system required a new administrative reform of local government. Actual reform 1719 - 1720 was a continuation of the first administrative reform. In May 1719, the territory of each province (there were 11 provinces in total by that time) was divided into several provinces; in the Petersburg province there were 11, in the Moscow province - 9, in the Kiev province - 4, etc. A total of 45 provinces were established, and soon their number increased to 50.

As an administrative-territorial unit, the province continued to exist; in the Senate and collegiums, all statements, lists and various information were compiled by provinces, but the governor's power extended only to the province of the provincial city. The province became the main unit of territorial division. The most important provinces were headed by governors-general, governors and vice-governors, and the rest of the provinces were governed by governors.

All of these officials had a very broad competence in the areas of administrative, police, financial and judicial matters. The instruction, given in January 1719 to the governors, determined in detail their rights and powers, specifically ordered "to watch that no walking people be found in his (governors - Ya. E.) province", to take care "so that violence and robbery it was not committed, and theft and all robberies and crimes were very much stopped and punished at their dignity. " Under the governors, special provincial offices were established.

The provinces were subdivided into districts - districts, headed by zemstvo commissars elected by the local nobility. These commissars had broad financial and police functions in their activities to capture fugitives and criminals, relied on elected peasant officials, as well as clerks of patrimonials and landowners.

Many new positions and institutions arose in each province. The chamberlain appointed by the Chamber Collegium, or the overseer of the zemstvo fees, headed the office of the chamberlain's affairs.

The body of the State Office-Board was the rentmaster (treasurer), who headed the rent, which accepted tax payments from payers, kept money and gave it out by order of the governor and chamberlain.

In addition, in each province there were: a recruitment office - an institution in charge of recruitment, an office of waldmeister affairs - state, mainly ship forests, a provisionmaster's office, provincial and city fiscal, an office of investigative affairs, an office of evidence of "souls" and other institutions and officials.