VI - XX centuries. Book: L. Evseeva, N. Komashko, M. Krasilin, etc. “History of Icon Painting: Origins, Traditions, Modernity. VI - XX centuries See also in other dictionaries

The icon - the heir to the antique portrait - has existed for almost two millennia. The icon owes its longevity in many respects to the conservatism of pictorial technique. The heyday of icon painting fell on the era of the Middle Ages, which so valued tradition, an era that preserved many secrets of the craft for mankind, inherited from antiquity and have not lost their attractiveness up to the present day.

History of icon painting of the VI-XX centuries - Origins - Traditions - Modernity

LILY EVSEEVA

NATALIA KOMASHKO

MIKHAIL KRASILIN

IGUMAN LUKA (GOLOVKOV)

ELENA OSTASHENKO

OLGA POPOVA

ENGELINA SMIRNOVA

IRINA YAZYKOVA

ANNA YAKOVLEVA

IP Verkhov S.I., 2014

ISBN 978-5-905904-27-1

Yazykov - History of icon painting of the VI-XX centuries - Origins - Traditions - Modernity - Contents

- Irina Yazykova, Hegumen Luka (Golovkov) THEOLOGICAL BASIS OF ICONS AND ICONOGRAPHY

- Anna Yakovleva ICON TECHNIQUE

- Olga Popova BYZANTINE ICONS OF VI-XV CENTURIES

- Lilia Evseeva GREEK ICON AFTER THE FALL OF BYZANTINE

- Engelina Smirnova ICON OF ANCIENT RUSSIA. XI-XVII CENTURIES

- Lilia Evseeva GEORGIAN ICON OF X-XV CENTURIES

- Elena Ostashenko ICONS OF SERBIA, BULGARIA AND MACEDONIA XV - XVII CENTURIES

- Natalya Komashko UKRAINIAN ICONOPIC BELARUSIAN ICON ICONOPY OF ROMANIA (MOLDOVA AND VALACHIA)

- Mikhail Krasilin RUSSIAN ICON OF THE XVIII - BEGINNING OF THE XX CENTURIES

- Irina Yazykova, Hegumen Luka (Golovkov) ICON OF THE XX CENTURY

Chronological table

Bibliography

List of illustrations

Glossary of terms

Yazykov - History of icon painting of the VI-XX centuries - Origins - Traditions - Modernity - an excerpt from the book

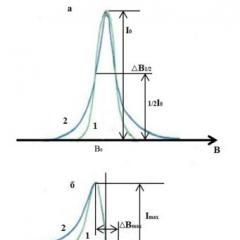

In the simplest way, icon-painting technique can be represented as the superposition of multi-colored layers of paint on top of each other, the basis for which is the plane of a white board primed with chalk or plaster (Fig. 1). Layering is its main property. Wishing to convey the originality of the medieval painting technique and compare it with the Renaissance, Talbot Rice and Richard Byron wrote: “the Byzantines layered, and the Italians modeled” 1. Because of this, the technique of medieval painting could easily "fold" and turn into a cursive system (cursive) by diminishing layers or "unfold" and become detailed by adding them.

Tradition connects the appearance of the first icon with Jesus Christ himself, who sent the Edessa king Abgar an image of his Face on a piece of cloth. The life of the Evangelist Luke, who created the icon of the Mother of God, testifies to the early experience of icon painting. From the "Libri Carolini", apparently belonging to the pen of Alcuin, it is known about the icons of Peter and Paul, presented by Pope Sylvester to Constantine the Great.

The history of art does not know such early examples of ancient icons, although one can get an idea of the pictorial experiences of the Jews who lived in the Hellenistic era from the paintings of the Old Testament cycle in the synagogue of Dura Europos, executed a little earlier than the middle of the 3rd century. Also well known are the images of the events of Sacred history, both Old Testament and New Testament, in murals, book miniatures and in works of applied art of the early Christian era - even before the adoption of Christianity as a state religion.

The oldest icons kept in the churches of Rome and on Sinai in the Pinakothek of St. Catherine's Monastery, where they happily escaped destruction during the reign of the iconoclastic emperors, date back to the 6th century. As a rule, they are written on a blackboard with wax paints - in a technique common to the entire Hellenistic world. Encaustic and its kind of "wax tempera" is the most perfect painting technique of antiquity, but it was not the only one. Ancient artists knew both mosaics, frescoes, and tempera. These techniques were inherited by the era of early Christianity, but not all of them survived until the Middle Ages. It is well known what damage the era of iconoclasm inflicted on the icon. During two centuries of persecution, not only the most ancient icons perished, but also several generations of icon painters.

The acts of the Seventh Ecumenical Council testify that, by order of the iconoclasts, wax and mosaics were scraped off the boards, the icons were thrown into the fire or smashed on the heads of icon-worshipers. The documents paint a picture of a terrible vandalism: along with the icons, both their admirers and icon painters perished from terrible torment and abuse. After iconoclasm, wax painting technique did not revive. Since the IX century. the technique of a pictorial icon, that is, executed with a brush and paints, is exclusively tempera.

Tempera, in the strict sense of the word, is a way of mixing paint with a binder. Paint is a dry powder - a pigment. It could be obtained by grinding stones (minerals and earths), metals (gold, silver, lead oxide), residues of organic origin (roots and twigs of plants, insects), dried and crushed, or boiled from dyed fabrics (purple, indigo). The binder is most often a yolk emulsion. But medieval craftsmen could use an emulsion of egg white as a binder, as the Bernese anonymous author writes, and gum, that is, the resin of trees, and animal and vegetable adhesives. They also knew about oil, but they tried not to use it, since they did not know the recipe for fast-drying oils.

Iconography (history)

In the Roman catacombs from the 2nd-4th centuries, works of Christian art have been preserved that are symbolic or narrative in nature.

The oldest icons that have come down to us date back to the 6th century and were made using the encaustic technique on a wooden base, which makes them related to Egyptian-Hellenistic art (the so-called "Fayum portraits").

The iconography of the main images, as well as the techniques and methods of icon painting, took shape by the end of iconoclastic times. In the Byzantine era, several periods are distinguished, differing in the style of images: “ Macedonian Renaissance"X - the first half of the XI century, icon painting of the Comnenian period 1059-1204," Palaeologus Renaissance»Early XIV century.

Iconography, together with Christianity, first came to Bulgaria, then to Serbia and Russia. The first Russian icon painter known by his name was Saint Alipy (Alimpiy) (Kiev,? - year). The earliest Russian icons were preserved not in the ancient temples of the south, which were destroyed during the Tatar invasions, but in the Cathedral of St. Sophia in Novgorod the Great. In Ancient Russia, the role of the icon in the temple has increased enormously (in comparison with the traditional Byzantine mosaics and frescoes). It is on Russian soil that a multi-tiered iconostasis is gradually taking shape. Iconography of Ancient Russia is distinguished by the expressiveness of the silhouette and the clarity of the combinations of large color planes, and greater openness to what is ahead in front of the icon.

The highest flowering of Russian icon painting reaches the XIV-XV centuries, the outstanding masters of this period are Theophanes the Greek, Andrei Rublev, Dionisy.

Original schools of icon painting are formed in Georgia, the South Slavic countries.

From the 17th century in Russia, the decline of icon painting began, icons began to be painted more "to order", and from the 18th century the traditional tempera (tempera) technique was gradually replaced by oil painting, which uses the techniques of the Western European art school: black and white modeling of figures, direct ("scientific" ) perspective, real proportions of the human body, and so on. The icon is as close as possible to the portrait. Secular, including non-believers, artists are involved in icon painting.

After the so-called "discovery of the icon" at the beginning of the 20th century, there was a great interest in ancient icon painting, the technology and attitude of which were preserved by that time almost only in the Old Believers' environment. The era of scientific study of the icon begins, mainly as a cultural phenomenon, completely divorced from its main function.

After the October Revolution, during the period of persecution of the Church, many works of church art were lost; the icon in the "country of victorious atheism" was assigned the only place - a museum, where it represented "ancient Russian art." Iconography had to be restored bit by bit. MN Sokolova (nun Juliana) played a huge role in the revival of icon painting. Among the emigre community, the "Icon" society in Paris was engaged in restoring the traditions of Russian icon painting.

Ideology

Schools and styles

Over the course of many centuries of the history of icon painting, many national icon painting schools have formed, which have undergone their own path of stylistic development.

Byzantium

Iconography of the Byzantine Empire was the largest artistic phenomenon in the Eastern Christian world. Byzantine artistic culture not only became the ancestor of some national cultures (for example, Old Russian), but throughout its existence influenced the icon painting of other Orthodox countries: Serbia, Bulgaria, Macedonia, Russia, Georgia, Syria, Palestine, Egypt. Also under the influence of Byzantium was the culture of Italy, especially Venice. Byzantine iconography and new stylistic trends emerging in Byzantium were of the greatest importance for these countries.

Pre-iconoclastic era

Apostle Peter. Encaustic icon. VI century. Monastery of St. Catherine on Sinai.

The oldest icons that have survived to our time date back to the 6th century. Early icons of the 6th-7th centuries preserve the ancient painting technique - encaustics. Some works retain certain features of antique naturalism and pictorial illusionism (for example, the icons "Christ Pantokrator" and "Apostle Peter" from the Monastery of St. Catherine on Sinai), while others are prone to conventionality, schematic representation (for example, the icon "Bishop Abraham" from the Dahlem Museum , Berlin, the icon "Christ and St. Mina" from the Louvre). A different, not antique, artistic language was characteristic of the eastern regions of Byzantium - Egypt, Syria, Palestine. In their icon painting, expressiveness was initially more important than knowledge of anatomy and the ability to convey volume.

Martyrs Sergius and Bacchus. Encaustic icon. VI or VII century. Monastery of St. Catherine on Sinai.

The process of changing ancient forms, their spiritualization by Christian art can be clearly seen on the example of the mosaics of the Italian city of Ravenna - the largest ensemble of early Christian and early Byzantine mosaics that have survived to our time. Mosaics of the 5th century (mausoleum of Galla Placidia, baptistery of the Orthodox) are characterized by vivid foreshortenings of figures, naturalistic modeling of volume, picturesque mosaic masonry. In the mosaics of the late 5th century (the Arian baptistery) and the 6th century (the basilicas of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo and Sant'Apollinare in Classe, the Church of San Vitale), the figures become flat, the lines of the folds of clothes are rigid, schematic. Poses and gestures freeze, the depth of space almost disappears. The faces lose their sharp individuality, the laying of the mosaic becomes strictly ordered.

The reason for these changes was the purposeful search for a special pictorial language capable of expressing Christian teachings.

Iconoclastic period

The development of Christian art was interrupted by iconoclasm, which had established itself as the official ideology of the empire since 730. This caused the destruction of icons and murals in churches. Persecution of icon-worshipers. Many icon painters emigrated to the distant ends of the Empire and neighboring countries - to Cappadocia, Crimea, Italy, partly to the Middle East, where they continued to create icons. Although in 787 at the Seventh Ecumenical Council iconoclasm was condemned as heresy and a theological justification for veneration of icons was formulated, the final restoration of icon veneration came only in 843. During the period of iconoclasm, instead of icons in churches, only images of a cross were used, instead of old murals, decorative images of plants and animals were made, secular scenes were depicted, in particular, horse races loved by Emperor Constantine V.

Macedonian period

After the final victory over the heresy of iconoclasm in 843, the creation of murals and icons for the churches of Constantinople and other cities began again. From 867 to 1056, the Macedonian dynasty ruled in Byzantium, which gave the name to the entire period, which is divided into two stages:

- Macedonian "Renaissance".

The Apostle Thaddeus presents to King Abgar the Image of Christ Not Made by Hands. Folding sash. X century.

King Abgar receives the Image of Christ Not Made by Hands. Folding sash. X century.

The first half of the Macedonian period was characterized by an increased interest in the classical ancient heritage. The works of this time are distinguished by their naturalness in the transmission of the human body, softness in the depiction of draperies, liveliness in the faces. Vivid examples of classicized art are: the mosaic of St. Sophia of Constantinople with the image of the Mother of God on the throne (mid-9th century), a folding icon from the monastery of St. Catherine on Sinai with the image of the Apostle Thaddeus and King Abgar receiving payment with the Image of the Savior Not Made by Hands (mid-10th century).

In the second half of the 10th century, icon painting retains its classic features, but icon painters are looking for ways to give the images more spirituality.

- Ascetic style.

In the first half of the 11th century, the style of Byzantine icon painting sharply changes in the direction opposite to the ancient classics. Several large ensembles of monumental painting have survived from this time: the frescoes of the Church of Panagia ton Chalkeon in Thessaloniki in 1028, the mosaics of the Catholicon of the Osios Lucas monastery in Phocis in the 30-40s. XI century, mosaics and frescoes of St. Sophia of Kiev of the same time, frescoes of St. Sophia of Ohrid mid - 3 quarters of the XI century, mosaics of Nea Moni on the island of Chios 1042-56. other .

Archdeacon Lawrence. Mosaic of St. Sophia Cathedral in Kiev. XI century.

All of these sites are characterized by the extreme degree of asceticism of images. The images are completely devoid of anything temporary and changeable. There are no feelings and emotions in the faces, they are extremely frozen, conveying the inner composure of the depicted. For this, huge symmetrical eyes with a detached, fixed gaze are emphasized. The figures freeze in strictly defined poses, often acquire squat, overweight proportions. Hands and feet become heavy, rough. Modeling of folds of clothes is stylized, becomes very graphic, only conventionally conveying natural forms. The light in the modeling acquires a supernatural brightness, bearing the symbolic meaning of Divine Light.

This stylistic trend includes the double-sided icon of Our Lady of Hodegetria with a perfectly preserved image of the Great Martyr George on the reverse (XI century, in the Assumption Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin), as well as many book miniatures. The ascetic trend in icon painting continued to exist later, manifesting itself in the XII century. An example is the two icons of Our Lady of Hodegetria in the Khilandar Monastery on Mount Athos and in the Greek Patriarchate in Istanbul.

Comnenian period

The Vladimir icon of the Mother of God. The beginning of the XII century. Constantinople.

The next period in the history of Byzantine icon painting falls on the reign of the Duc, Comnenian and Angels dynasties (1059-1204). In general, it is called Komnenos. In the second half of the 11th century, asceticism was replaced by the classical form and harmony of the image. The works of this time (for example, Daphne's mosaics around 1100) achieve a balance between the classical form and the spirituality of the image, they are graceful and poetic.

The creation of the Vladimir Icon of the Mother of God (Tretyakov Gallery) dates back to the end of the 11th century or the beginning of the 12th century. This is one of the best images of the Comnenian era, undoubtedly the work of Constantinople. In 1131-32. the icon was brought to Russia, where it became especially revered. Only the faces of the Mother of God and the Child have survived from the original painting. The beautiful face of the Mother of God, filled with subtle sorrow for the suffering of the Son, is a characteristic example of the more open and humanized art of the Comnenian era. At the same time, on his example, one can see the characteristic physiognomic features of Komnen's painting: an elongated face, narrow eyes, a thin nose with a triangular fossa on the bridge of the nose.

Saint Gregory the Wonderworker. Icon. XII century. Hermitage Museum.

Christ Pantokrator the Merciful. Mosaic icon. XII century.

The mosaic icon "Christ Pantokrator the Merciful" from the State Museums of Dahlem in Berlin dates back to the first half of the 12th century. It expresses the inner and outer harmony of the image, concentration and contemplation, the Divine and the human in the Savior.

Annunciation. Icon. End of the XII century. Sinai.

In the second half of the 12th century, the icon "Gregory the Wonderworker" was created from the State. The Hermitage. The icon is distinguished by its magnificent Constantinople letter. In the image of the saint, the individual principle is especially strongly emphasized; before us is, as it were, a portrait of a philosopher.

- Comnenian mannerism

![]()

Crucifixion of Christ depicting saints in the fields. Icon of the second half of the 12th century.

In addition to the classical trend, other trends appeared in icon painting of the 12th century, inclined to a violation of balance and harmony in the direction of a greater spiritualization of the image. In some cases, this was achieved by an increased expression of painting (the earliest example is the frescoes of the Church of St. Panteleimon in Nerezi in 1164, the icons "Descent into Hell" and "Dormition" of the late 12th century from the monastery of St. Catherine on Sinai).

In the latest works of the 12th century, the linear stylization of the image is extremely enhanced. And draperies of clothes and even faces are covered with a network of bright whitewash lines, which play a decisive role in building the form. Here, as before, light has the most important symbolic meaning. The proportions of the figures are also stylized, which become excessively elongated and thin. Stylization reaches its maximum manifestation in the so-called late Comnenian mannerism. This term refers primarily to the frescoes of the Church of St. George in Kurbinovo, as well as a number of icons, for example, the "Annunciation" of the late 12th century from the collection at Sinai. In these paintings and icons, the figures are endowed with sharp and impetuous movements, the folds of clothes are intricately curled, the faces have distorted, specifically expressive features.

There are also examples of this style in Russia, for example, frescoes of the Church of St. George in Staraya Ladoga and the reverse of the icon "The Savior Not Made by Hands", which depicts the worship of angels to the Cross (Tretyakov Gallery).

XIII century

The flourishing of icon painting and other arts was interrupted by the terrible tragedy of 1204. This year, the knights of the Fourth Crusade captured and desperately plundered Constantinople. For more than half a century, the Byzantine Empire existed only as three separate states with centers in Nicaea, Trebizond and Epirus. The Latin Empire of the Crusaders was formed around Constantinople. Despite this, icon painting continued to develop. The 13th century is marked by several important stylistic phenomena.

Saint Panteleimon in his life. Icon. XIII century. Monastery of St. Catherine on Sinai.

Christ Pantokrator. Icon from the Khilandar monastery. 1260s

At the turn of the XII-XIII centuries, a significant change in style took place in the art of the entire Byzantine world. Conventionally, this phenomenon is called "art around 1200". Calmness and monumentalism are replacing linear stylization and expression in icon painting. The images become large, static, with a clear silhouette and sculptural, plastic form. A very characteristic example of this style is the frescoes in the monastery of St. John the Evangelist on the island of Patmos. A number of icons from the monastery of St. Catherine on Sinai: "Christ Pantokrator", mosaic "Mother of God Hodegetria", "Archangel Michael" from the Deesis, "Sts. Theodore Stratilat and Demetrius of Thessaloniki. All of them show the features of the new direction, making them different from the images of the Comnenian style.

At the same time, a new type of icons arose - hagiographic icons. If earlier scenes of the life of this or that saint could be depicted in the illustrated Minology, on epistyles (long horizontal icons for altar barriers), on the folds of triptychs, now scenes of life ("stamps") began to be placed along the perimeter of the centerpiece of the icon, which depicts the saint himself. The collection at Sinai contains the hagiographic icons of St. Catherine (full-length) and St. Nicholas (half-length).

In the second half of the 13th century, classical ideals predominate in icon painting. The icons of Christ and the Mother of God from the Khilandar Monastery on Mount Athos (1260s) have the correct, classical form, the painting is complex, nuanced and harmonious. There is no tension in the images. On the contrary, the lively and concrete gaze of Christ is calm and welcoming. In these icons, Byzantine art came to the maximum possible degree of closeness of the Divine to the human. In 1280-90 art continued to follow the classical orientation, but at the same time, a special monumentality, power and emphasis of techniques appeared in it. Heroic pathos manifested itself in the images. However, due to the excessive intensity, the harmony has somewhat diminished. A striking example of icon painting at the end of the 13th century is the Evangelist Matthew from the icon gallery in Ohrid.

- Crusader workshops

A special phenomenon in icon painting is the workshops created in the east by the crusaders. They combined the features of European (Romanesque) and Byzantine art. Here Western artists adopted the techniques of Byzantine writing, and the Byzantines performed icons that were close to the tastes of the crusader customers. The result is an interesting fusion of two different traditions, variously intertwined in each individual piece. Crusader workshops existed in Jerusalem, Acre, Cyprus and Sinai.

Palaeologus period

The founder of the last dynasty of the Byzantine Empire, Michael VIII Palaeologus, returned Constantinople to the hands of the Greeks in 1261. He was succeeded on the throne by Andronicus II (reigned 1282-1328). At the court of Andronicus II, exquisite art flourished magnificently, corresponding to the chamber court culture, which was characterized by excellent education, an increased interest in ancient literature and art.

- Palaeologus Renaissance- so it is customary to call a phenomenon in the art of Byzantium in the first quarter of the XIV century.

![]()

Icon "Annunciation" from the Church of St. Clement in Ohrid. XIV century.

While retaining the church content, icon painting takes on extremely aestheticized forms, experiencing the strongest influence of the ancient past. It was then that miniature mosaic icons were created, intended either for small, chamber chapels, or for noble customers. For example, the icon "St. Theodore Stratilates" in the collection of the State Hermitage. The images on such icons are unusually beautiful and amaze with the miniature work. The images are either calm, without psychological or spiritual depth, or, on the contrary, sharply characteristic, as if portrait. Such are the images on the icon with four saints, also in the Hermitage.

Many icons have also survived, painted in the usual tempera technique. They are all different, the images are never repeated, reflecting different qualities and states. So in the icon "Our Lady of Psychostria (Soul Savior)" from Ohrid, firmness and strength are expressed, in the icon "Our Lady of Hodegetria" from the Byzantine Museum in Thessaloniki opposite lyricism and tenderness are conveyed. On the reverse side of "Our Lady of Psychostria" is depicted "Annunciation", and on the icon of the Savior, paired with her, on the reverse side there is written "The Crucifixion of Christ", in which pain and sorrow, overcome by the strength of the spirit, are sharply conveyed. Another masterpiece of the era is the icon "Twelve Apostles" from the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts. Pushkin. In it, the images of the apostles are endowed with such a vivid individuality that, it seems, we have a portrait of scientists, philosophers, historians, poets, philologists, humanitarians who lived at the imperial court in those years.

All these icons are characterized by impeccable proportions, flexible movements, imposing staging of figures, stable poses and easy-to-read, verified compositions. There is a moment of entertainment, the concreteness of the situation and the presence of characters in space, their communication.

- Second half of the XIV century

Mother of God Periveptos. Icon of the second half of the XIV century. Sergiev Posad Museum-Reserve.

Don icon of the Mother of God. Theophanes the Greek (?). End of the XIV century. Tretyakov Gallery.

Praise to the Mother of God with akathist. Icon of the second half of the XIV century. Assumption Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin.

"Archangel Gabriel" from the Vysotsky rank.

John the Baptist. Icon from the Deesis order of the late 14th century. Cathedral of the Annunciation in the Moscow Kremlin.

In the 50s. XIV century Byzantine icon painting is experiencing a new upsurge, based not only on the classical heritage, as it was in the decades of the "Palaeologus Renaissance", but especially on the spiritual values of the victorious hesychasm. The tension and gloom that appeared in the works of the 30-40s are leaving the icons. However, now the beauty and perfection of form are combined with the idea of transforming the world with Divine light. The theme of light in the painting of Byzantium has always taken place in one way or another. Light was understood symbolically as a manifestation of the Divine power permeating the world. And in the second half of the XIV century, in connection with the doctrine of hesychasm, such an understanding of the light in the icon became all the more important.

An excellent work of the era is the icon "Christ Pantokrator" from the Hermitage collection. The image was created in Constantinople for the Pantokrator monastery on Mount Athos, the exact year of its execution is known - 1363. The image surprises both with the external beauty of the painting, the perfection in the transfer of the form of the face and hands, and the very individual image of Christ, close and open to man. The colors of the icon seem to be permeated with an inner glow. In addition, the light is depicted in the form of bright whitewash strokes on the face and hand. This is how the pictorial technique clearly conveys the doctrine of the uncreated Divine energies that permeate the whole world. This technique is becoming especially common.

After 1368, an icon of St. Gregory Palamas himself (The Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts), glorified in the face of saints, was painted. His image is also distinguished by enlightenment, individuality (literally portraiture) and contains a similar technique of bleaching "engines" or "lights".

Close to the image of Christ from the GE is the icon of the Archangel Michael from the Byzantine Museum in Athens, the icon of Our Lady of Periveptos, kept in Sergiev Posad, and many others. Some paintings are rich in rich shades of colors, while others are somewhat more austere.

The best qualities of Byzantine art at the beginning of the 15th century were embodied in the work of the great Russian icon painter, the Monk Andrei Rublev.

Ancient Russia

The beginning of Russian icon painting was laid after the Baptism of Rus. Initially, the oldest Russian stone churches in Kiev and other cities, as well as their paintings and icons, were created by Byzantine craftsmen. However, already in the 11th century, there was a school of its own in the Kiev-Pechersk Monastery, which gave birth to the first famous icon painters - the Monks Alypy and Gregory.

The history of ancient Russian art is usually divided into "pre-Mongol" and subsequent, since the historical circumstances of the XIII century significantly influenced the development of the culture of Russia.

Although in the XIV century the influence of Byzantium and other Orthodox countries on Russian icon painting was great, Russian icons showed their own original characteristics even earlier. Many Russian icons are the best examples of Byzantine art. Others - created in Novgorod, Pskov, Rostov and other cities - are very peculiar, distinctive. The work of Andrei Rublev is at the same time a wonderful heritage of the traditions of Byzantium and embraces the most important Russian features.

Serbia, Bulgaria, Macedonia

In Bulgarian medieval art, icon painting appeared simultaneously with the adoption of Christianity in 864. The prototype was Byzantine icon painting, but soon it mixed with the existing local traditions. The ceramic icons are quite unique. On the base (ceramic tiles), a drawing was applied with bright colors. These icons differed from the Byzantine school of icon painting by their greater roundness and liveliness of their faces. Due to the fragility of the material, very few works in this style have survived to our time, moreover, only fragments of the majority have remained. In the era of the Second Bulgarian Kingdom, there were two main trends in icon painting: folk and palace. The first is associated with folk traditions, and the second originates from the Tarnovo art school of painting, which was greatly influenced by the art of the Renaissance. The most frequently encountered character in Bulgarian icon painting is St. John of Rila. In the days when Bulgaria was part of the Ottoman Empire, icon painting, Slavic writing and Christianity helped preserve the people's identity of the Bulgarians. The National Revival of Bulgaria brought some renewal to icon painting. The new style, close to folk traditions, did not contradict the basic canons of the genre. Bright, cheerful colors, characters in costumes of the modern era, frequent depictions of Bulgarian kings and saints (forgotten during the Ottoman yoke) are the hallmarks of the icon painting of the Bulgarian Renaissance.

Other books on similar topics:

| author | Book | Description | Year | Price | Book type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lilia Evseeva, Natalia Komashko, Mikhail Krasilin, Hegumen Luka (Golovkov), Elena Ostashenko, Engelina Smirnova, Irina Yazykova, Anna Yakovleva | History of Iconography. Origins. Traditions. Modernity | Gift edition with beautiful color illustrations. From the Contents: Theological foundations of the icon. Iconography. Technique icons. Byzantine icons of the 6th-15th centuries Greek icon after the fall of Byzantium ... - @ Verkhov S. I., @ (format: 2000x1440, 288 pages) @ Album with illustrations @ @ | 2014 | 763 | paper book |

See also other dictionaries:

The Evangelist Luke paints the icon of the Mother of God (Mikhail Damaskin, 16th century) ... Wikipedia

Christo ... Wikipedia

Wikipedia has articles about other people with this surname, see Chirikov. Osip Semyonovich Chirikov Birth name: Osip (Joseph) Semyonovich Chirikov Date of birth: XIX century Place of birth: Mstera, Msterskaya volost, Vyaznikovsky uye ... Wikipedia

Apostle Peter, early 6th century Board ... Wikipedia

Spaso-Preobrazhensky Cathedral in ... Wikipedia

- "The Holy Trinity" by Andrei Rublev (1410) Iconography (from ... Wikipedia

BYZANTINE EMPIRE. PART IV- Fine art is the most important in Christ. culture and the most extensive part of the artistic heritage of Britain in terms of the number of preserved monuments. Chronology of the development of the Byzantines. art does not quite coincide with the chronology ... ... Orthodox encyclopedia

John the Forerunner- [John the Baptist; Greek ᾿Ιωάννης ὁ Πρόδρομος], who baptized Jesus Christ, the last Old Testament prophet who revealed to the chosen people Jesus Christ as the Messiah the Savior (commemorated on June 24, Nativity of John the Baptist, August 29. Beheading of the head of John ... ... Orthodox encyclopedia

RSFSR. I. General Information The RSFSR was formed on October 25 (November 7) 1917. It borders on the northwest with Norway and Finland, on the west with Poland, in the southeast with China, the Mongolian People's Republic, and the DPRK, as well as with the union republics of to the USSR: to the west from ... ... Great Soviet Encyclopedia

Udmurtia is a republic within the Russian Federation, is its integral subject, part of the Volga Federal District, located in the western Cis-Urals, in the interfluve of the Kama and its right tributary Vyatka. The country is inhabited ... ... Wikipedia

JOHN ZLATOUST. Part II- Doctrine Considering correct faith a necessary condition for salvation, IZ at the same time urged to believe in simplicity of heart, not showing excessive curiosity and remembering that “the nature of rational arguments is like a kind of labyrinth and networks, nowhere has ... Orthodox encyclopedia