Old Believer monasteries of Altai: from Nikon’s reforms to the present day

The first Old Believers came to Altai from the previously developed northern Siberian territories. Some of them were among other Russian settlers who fell under government decrees on the settlement of new lands in connection with the founding of fortresses and factories. Others were fugitives hiding in the inaccessible gorges of the Altai Mountains from government duties, serfdom, conscription, and religious persecution. The reason for the increasing frequency of escapes was the introduction in the 20s. XVIII century double salary from the Old Believers, as well as a decree of 1737 on the involvement of schismatics in mining work at state-owned factories.

The Bukhtarma Valley was often the final destination of many fugitives. It was known as Stone, i.e. mountainous part of the region, so its inhabitants were called masons. Later, these lands began to be called Belovodye, identifying the free land, devoid of government supervision, with the mythical country from the utopian legend extremely widespread among the Old Believers. Its numerous versions say that Belovodye is a holy land where Russian people live who fled the religious strife of the 17th century. In Belovodye they have their own churches, in which worship is conducted according to old books, the sacraments of baptism and marriage are performed according to the sun, they do not pray for the king, they cross themselves with two fingers. “In those places there is no theft and theft and other things contrary to the law... And there are all sorts of earthly fruits, and gold and silver are countless... They have no secular court, there are no police or guards there, but they live according to Christian custom. God fills this place." However, only true zealots of ancient piety can enter Belovodye. “The road there is forbidden to the servants of the Antichrist... You must have unshakable faith... If you waver in your faith, the fair land of Belovodsk will be covered with fog.” Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries there is a tireless search for this fantastic country. After fruitless attempts to find the Belovodsk land, many of its seekers began to consider the Bukhtarminsky region as Belovodye, where “the land of peasants is without officials and priests.” It was the latter that attracted the Old Believers there.

The government has known about secret settlements deep in the Altai Mountains since the 40s. XVIII century, but they were discovered only in 1761, when ensign Zeleny, going with a mountain search party to Bukhtarma, noticed near one of its tributaries - Turgusun - a hut in which there were two men who then managed to hide. Such single houses and small villages of five or six households were scattered among the mountain gorges of the Bukhtarma Valley. Their inhabitants were engaged in fishing, hunting, and farming.

However, difficult living conditions, internal strife, frequent crop failures, as well as the constant danger of discovery, since ore miners began to appear in these places, forced the Bukhtarminians to legalize their situation. In 1786, about 60 residents of Stone went to the Chinese Bogdykhan with a request to take them under his guardianship. But, not wanting a conflict with the Russian government, the Chinese authorities, having kept the petitioners in custody in the city of Khobdo, released them with refusal.

In 1790, taking advantage of the appearance of a mining official with a party of workers, the Bukhtarma residents expressed to him their desire “to be transparent to the government.” By a rescript of Catherine II of September 15, 1791, masons were accepted into Russia as tribute-bearing foreigners. They paid the government with tribute in the form of furs and animal skins, like all other foreigners Russian Empire. In 1796, yasak was replaced by cash taxes, and in 1824. - quitrent as from settled foreigners. In addition, the Bukhtarma residents were exempt from subordination to the sent administration, mining and factory work, recruiting and some other duties.

After receiving official status as Russian subjects, masons moved to more convenient places to live. In 1792, instead of 30 small settlements, 9 villages were formed, in which just over 300 people lived: Osochikha (Bogaty-revo), Bykovo, Sennoye, Korobikha, Pechi, Yazovaya, Belaya, Fykalka, Malonarymskaya (Ognevo).

In 1760, a Senate decree was issued “On occupying places in Siberia from the Ust-Kamenogorsk fortress along the Bukhtarma River and further to Lake Teletskoye, on building fortresses there in convenient places and settling that side along the Ube, Ulba, Berezovka, Glubokaya and other rivers.” rivers flowing into the Irtysh River, Russian people up to two thousand people." In this regard, the Senate, based on the manifesto of Catherine II of December 4, 1761, invited Russian Old Believers who fled from religious persecution to Poland to return to Russia. At the same time, it was indicated that they could choose either the previous place of residence or one designated at the disposal of the empress, which included Siberia.

In 1765, a special order was issued, which ordered that fugitives from Poland and Lithuania be exiled to Siberia, so in Altai they began to be called Poles.

In the 1760s all the indigenous villages of the “Poles” were founded in the Zmeinogorsk district: Ekaterininka, Alexandrovskaya volost; Shemonaikha, Losikha (Verkh-Uba), Sekisovka, Vladimir volost; Bobrovka, Bobrovskaya volost. Soon new villages appeared, where the inhabitants were only Old Believers: Malaya Ubinka, Bystrukha, Vladimir volost; Cheremshanka, Butakovo, Ridder volost and some others.

Thus, the history of the Altai Old Believers of the 18th century. is divided into two stages: the first half of the century, when only a few Old Believers - fugitives - entered the region, and the second half - the time of the formation of settled settlements in this territory (in the 1750-1790s - masons, in the 1760-1800s. - Poles). XIX century characterized by a general stabilization of the life of the Altai Old Believers. This is evidenced by the active process of formation of new villages, the establishment of connections between various Old Believer sects, due to their religious community.

With the establishment Soviet power in the region since the 20s. In the 20th century, religious oppression began: houses of worship were closed, believers were persecuted, religious customs and traditions were desecrated. A lot of spiritual literature was confiscated, iconostases were destroyed. Many communities have lost competent charter leaders. The Old Believers again went “underground”, once again suffering oppression and persecution from the state

And only in Lately there is a religious revival, as evidenced by the registration of Old Believer communities throughout the region, the opening of new prayer houses, the attraction of the younger generation to the communities, the resumption of teaching hook singing (in particular, in the parishes of Barnaul, Biysk, Ust-Kamenogorsk), etc. However, such processes do not appear everywhere. Far from urban centers populated areas reverse trends of destruction and extinction of spiritual traditions prevail.

Altai elders are characterized by ritual features. In particular, when receiving communion, they do not use prosphora, but Epiphany water (Multa village Ust-Koksinsky district), on Easter - an egg that had lain for a year in front of the icons since last Easter (village of Yailyu, Turochak district). When transitioning to the old age, Nikonians must be baptized again, while Belokrinichniks are baptized with “renunciation” (denial of heresy). According to F.O. Bochkareva from the village of Tikhonkaya, “in order to accept our faith, before being baptized, it is necessary to study the charter for three years. We will find the interpretation of this in the Gospel parable about the owner and the gardener, who for three years looked after a tree that bloomed only in the fourth year.”

The spiritual leader of the elderly community is the abbot. According to V.I. Filippova from Gorno-Altaisk, “the rector is almost a priest. He has the right to remove people from the cathedral and bring together those getting married.” In Multa, the abbot retains the title “priest”; all problems are resolved by the council (i.e., the community) during a spiritual conversation. The most controversial dogmatic issues include the funeral of the deceased without repentance.

The Old People deliberately do not spread their faith. “We must hide our faith so that outsiders do not ridicule the Scriptures, do not consider everything that is written there as fairy tales and fables. Our faith will not die from this, it will only become thinner and stretched into a thread,” states F.O. Bochkareva.

It is known that in the mountains on Lake Teletskoye there are monasteries and a convent for the elderly.

According to the message of Old Believer A. Isakova from the village. Chendek, Ust-Koksinsky district, the old man’s church used to be in Katanda. She said that the Old Believers of Koksa communicated with the Bukhtarma people, as well as the Kerzhaks of Biysk and Barnaul. Currently, the center of the Koksa old man community is the village of Multa. Old people from Chendek, Upper and Lower Uimon, Tikhonkaya come here for big holidays...

The more than 250-year history of the Altai Old Believers continues to develop, enriched with new events and facts. The uniqueness of this region is largely due to the multi-layered Old Believer culture. Along with the old-time layer of Altai Old Believers, there is a group of later settlers. A large number of interpretations and agreements on the territory of Altai introduces additional fragmentation and indicates the heterogeneity of the phenomenon being studied. Constant migration processes associated with the outflow of population due to political events, discoveries and development of ore deposits, large construction projects, for example, such as the Bukhtarma hydroelectric power station, give a dynamic character to the map of Old Believer settlements.

There is no doubt that Altai is one of the most interesting and promising regions for the study of the Old Believers, therefore the systematic collection of material in order to study the current state of the Altai Old Believers must be continued in the future, which will complement and expand our understanding of this unique historical and cultural phenomenon.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Masons (Bukhtarma masons, Bukhtarma Old Believers, Altai masons, Bukhtarma people) are an ethnographic group of Russians, formed in the 18th - 19th centuries on the territory of Southwestern Altai in numerous inaccessible mountain valleys of the Bukhtarma River basin and the high-mountainous Uimon steppe at the source of the Katun River. The name comes from the old Russian designation for mountainous terrain - “stone”. It was formed from families of Old Believers, mainly non-priests of the Pomeranian consent, and other fugitives from government duties - Old Believers, mining peasants, recruits, serfs, convicts and later settlers.

The historical dialect of the language is Okaya.

Due to the shortage of women, mixed marriages occurred with local Turkic and Mongolian peoples (the bride was required to accept the Old Belief), the children were considered Russian. The influence of Kazakh traditions on the life and culture of masons is noticeable in elements of clothing, household items, some customs, and knowledge of the language. There was a custom of adopting other people's children, regardless of nationality. Illegitimate children bore the surname of their maternal grandfather and enjoyed the same rights as “legitimate” children. To avoid consanguineous marriages, Old Believers remembered up to nine generations of ancestors.

Researchers have noted the great prosperity of the Bukhtarma masons, due to the minimal pressure of state duties, the internal system of self-government and mutual assistance, a special character, the generous natural resources of the region, and the use of hired workers. Until collectivization, masons represented a very closed and local society, with their own distinctive culture and traditional way of life - according to the conservative norms and rules of Orthodox Old Believer communities, with a strong limitation of external contacts.

The founder of the Bukhtarma freemen was considered to be the peasant Afanasy Seleznev, as well as the Berdyugins, Lykovs, Korobeinikovs, and Lysovs. Their descendants still live in villages on the banks of the Bukhtarma.

The masons hunted agriculture, fishing, beekeeping, and later deer breeding. They exchanged furs and food obtained for goods from their neighbors - Siberian Cossacks, Kazakhs, Altaians, Chinese, as well as visiting Russian merchants. Villages were built near rivers, and a mill and a forge were always installed in them. In 1790 there were 15 villages. Some of the masons left the Bukhtarma Valley further into the mountains, to the Argut and Katun rivers. They founded the Old Believer village of Uimon and several other settlements in the Uimon Valley.

Old Believers, Old Believers or schismatics appeared in Russia in 1653 - Patriarch Nikon promoted church reform and caused a split in the ranks of the Orthodox people. The Old Believers were anathematized, and they were forced to flee to remote places in Russia, and developed the hard-to-reach corners of Altai. The first Old Believers in Altai appeared in the eighteenth century, in the forties. They inhabited the upper reaches of the Uba and Ulba rivers, settled on Belaya, Koksa and Uimon, Argut and Katun. Many schismatics strove to the valley of Bukhtarma or Kamen (the second name of the river). The Bukhtarmin residents were dubbed masons. Later, the Bukhtarma valley began to be called Belovodye - it was a land free from royal taxes and supervision.

The descendants of the first Old Believers in Altai still live on Bukhtarma. Old Believers from both the European part of the Russian state and residents of the previously developed northern regions of Siberia flocked to the mountainous region. In addition to the fugitives, many government migrants settled in Altai, who came to the mountains to “develop new lands.” Some schismatics were brought to Altai by force. Among them were fugitives to Poland and Lithuania, who later became known as Poles. Old Believers in Altai were forced to hide from the authorities; only in 1792, after the introduction of yasak (tax for foreigners), their position became legalized. In Soviet times, Old Believers were persecuted. Despite the dramatic history, some schismatics managed to preserve ancient traditions, which makes their life attractive to scientists and tourists.

Old Believers are extremely hardy, clean, enterprising and hard-working people. In terms of hard work and accuracy, they are compared only with the German Mennonites. They were able to adapt to the natural extremes of the Altai Mountains and learned to use the natural resources of this luxurious region. The Raskolniks took up hunting and fishing, kept bees and bred Red deer. Farmers and artisans worked successfully. Among the latter, famous were weavers and carpenters, potters (the latter, mostly women). The families of the Old Believers always lived in abundance, prosperously, although most of them had many children, and even adopted orphans, regardless of their roots. The masons were distinguished by their mercy, willingness to selflessly help those in need, and mutual assistance. Severe natural conditions They developed courage, determination and frugality.

The lack of women among the Old Believers led to many mixed marriages. After the adoption of the Old Believers, Russians, Chinese women, and representatives of local Turkic peoples became the wives of schismatics. This left an interesting imprint on the customs of the Old Orthodox. Old Believers in Altai adhere to different interpretations, which explains the heterogeneity of the Old Believers. And today there are communities closed to contacts that, in the name of purity of spirit and faith, limit connections with the outside world. Among the Old Believers there are individuals who have refused passports and pensions, believing that these benefits come from evil spirits. They do not have televisions or radios and consider using electricity a sin.

The history of the Altai Old Believers, closely connected with the development of Siberia by Russian settlers, is widely covered in scientific research. Scientists have created a large factual base based on materials from Siberian chronicles, government documents, statistical data, and literary monuments. The information obtained reveals a variety of problems: the appearance of Old Believers in the region, their adaptation to new living conditions, migration processes, customary legal relations, family life, cultural traditions, etc. Among the most fundamental works of historical Siberian studies, touching on the topic of Altai Old Believers, the academic work “History of Siberia from Ancient Times to the Present Day”, the monograph “Bukhtarma Old Believers”, books by N.V. Alekseenko, Yu.S. Bulygina, N.N. Pokrovsky, N.G. Apollova, N.F. Emelyanova, V.A. Lipinskaya, T.S. Mamsik. Research by modern scientists takes into account the achievements of figures historical science XIX - early XX centuries: S.I. Gulyaev, G.N. Potanin, A. Printsa, P.A. Slovtsova, D.N. Belikova, E. Shmurlo, M. Shvetsova, B. Gerasimova, G.D. Grebenshchikova, I.V. Shcheglova, N.M. Yadrintseva. The research of these, as well as a number of other researchers, gives a holistic picture of initial stages history of the Altai Old Believers and its further development.

The annexation of Siberia to Russia dates back to the end of the 16th century. This process is connected with Ermak’s campaign. The region of primary development of Siberian lands was the Tobolsk province. By the middle of the 17th century. Russian settlers occupied lands from Verkhoturye to Tobolsk. Since the main, and perhaps the only possible, way to move deeper was rivers, the development of Siberia initially took place along the currents of the Ob and Irtysh.

Then the settlers began to settle in more convenient places - along the southern tributaries of Siberian rivers. N.M. Yadrintsev identified general pattern resettlement processes, such as movement by river from less fertile to more fertile places. This is how the formation of the most densely populated regions of Siberia proceeded. At the beginning of the 18th century. As a result of the pushing back of the nomadic Siberian tribes to the Chinese border, the land holdings of the Russian state expanded. Powerful migration flows poured into the south of Siberia - to the foothills of Altai and further through Semirechye to the Amur. Thus, Altai is an area of rather late development of Siberian lands by Russian people (1).

The process of colonization of Siberia, including Altai, followed two paths - government, which included military, industrial and so-called government resettlement, i.e. sending to Siberia in connection with some royal decree, and free people, associated with the secret escape of people from oppression and duties. The Russian settlers included military men, Cossacks, who traveled to strengthen and expand border lines, protect fortresses, outposts and forts; ore miners and industrialists who mastered the Siberian Natural resources; peasant farmers sent by the tsarist administration to new industrial zones; runaway exiles, convicts, and finally, just “walking people” looking for free lands.

The motley old-timer population also had religious differences. Here we should highlight representatives of pre-reform Orthodoxy who came to Altai as a result of internal migration of the population from Tobolsk, whose ancestors ended up in Siberia back in late XVI- the first half of the 17th century, New Believers-Nikonians, who accepted in the second half of the 17th century. church reform, and the Old Believers who rejected the innovations of Patriarch Nikon. The Old Believers formed a completely separate group among the Siberian population. In the areas of primary development of Siberia by Russian settlers, Old Believers appeared soon after the split. The massive spread of the Old Believers in Siberia began in the last quarter of the 17th century. The facts of the burning of schismatics by the Tobolsk authorities in 1676 and 1683-1684, the self-immolation of Old Believers in Berezovsky on the Tobol River in 1679, in Kamensky near Tyumen and in Kurgayskaya Sloboda in 1687 are documented. On the territory of Siberia, the Old Believers spread in accordance with the general the direction of advancement of the Russian population - from the northwest to the southeast. Old Believers appeared in Altai no earlier than the 18th century, which is confirmed by documentary sources and historical research.

The first Old Believers came to Altai from the previously developed northern Siberian territories. Some of them were among other Russian settlers who fell under government decrees on the settlement of new lands in connection with the founding of fortresses and factories. Others were fugitives hiding in the inaccessible gorges of the Altai Mountains from government duties, serfdom, conscription, and religious persecution. The reason for the increasing frequency of escapes was the introduction in the 20s. XVIII century double salary from the Old Believers, as well as the order of 1737 on the involvement of schismatics in mining work at state-owned factories (2).

It should be noted that in remote areas of Altai, free popular colonization preceded the government development of these lands. This is how settlement took place in the upper reaches of the Uba, Ulba and further south along the Bukhtarma, Belaya, Uimon, and Koksa rivers. A. Printz believed that the first Old Believers appeared here back in the 20s. XVIII century, but documentary evidence dates back only to the 40s. XVIII century Then secret settlements of desert dwellers were discovered on the river. Ube, united around the monk Kuzma. In 1748, two factory workers were caught trying to escape through Uba to the Bukhtarma valley. As it turned out, their route was already well-trodden by their predecessors, which indicates an earlier secret development of these places.

The Bukhtarma Valley was often the final destination of many fugitives. It was known as Stone, i.e. mountainous part of the region, so its inhabitants were called masons. Later, these lands began to be called Belovodye, identifying the free land, devoid of government supervision, with the mythical country from the utopian legend extremely widespread among the Old Believers. In its numerous versions (3) it is said that Belovodye is a holy land where Russian people live who fled the religious strife of the 17th century. In Belovodye they have their own churches, in which worship is conducted according to old books, the sacraments of baptism and marriage are performed according to the sun, they do not pray for the king, they cross themselves with two fingers.

“In those places there is no theft and theft and other things contrary to the law... And there are all sorts of earthly fruits, and gold and silver are innumerable... They have no secular court, there are no police or guards there, but they live according to Christian custom. God fills this place." However, only true zealots of ancient piety can enter Belovodye. “The road there is forbidden to the servants of the Antichrist... You must have unshakable faith... If you waver in faith, the fair land of Belovodsk will be covered with fog” (4).

As E. Shmurlo notes, throughout the entire 18th and 19th centuries there is a tireless search for this fantastic Eldorado, where rivers flow with honey, where taxes are not collected, where, finally, Nikon’s church does not exist specifically for schismatics.

Among the Old Believers there were numerous lists of the “Traveller” indicating the way to Belovodye. The last real geographical point of the route is the Bukhtarma valley. After fruitless attempts to find the Belovodsk land, many of its seekers began to consider the Bukhtarminsky region as Belovodye, where “the land of peasants is without officials and priests.” It was the latter that attracted the Old Believers there.

The government has known about secret settlements deep in the Altai Mountains since the 40s. XVIII century, but they were discovered only in 1761, when ensign Zeleny, going with a mountain search party to Bukhtarma, noticed near one of its tributaries - Turgusun - a hut in which there were two men who then managed to hide. Such single houses and small villages of five or six households were scattered among the mountain gorges of the Bukhtarma Valley. Their inhabitants were engaged in fishing, hunting, and farming.

However, difficult living conditions, internal strife, frequent crop failures, as well as the constant danger of discovery, since ore miners began to appear in these places, forced the Bukhtarminians to legalize their situation. In 1786, about 60 residents of Stone went to the Chinese Bogdykhan with a request to take them under his guardianship. But, not wanting a conflict with the Russian government, the Chinese authorities, having kept the petitioners in custody in the city of Khobdo, released them with refusal.

In 1790, taking advantage of the appearance of a mining official with a party of workers, the Bukhtarma residents expressed to him their desire “to be transparent to the government.” By a rescript of Catherine II of September 15, 1791, masons were accepted into Russia as tribute-bearing foreigners. They paid the government with tribute in the form of furs and animal skins, like all other foreigners of the Russian Empire. In 1796, yasak was replaced by a cash tax, and in 1824 - by quitrent as from settled foreigners. In addition, the Bukhtarma residents were exempt from subordination to the sent administration, mining work, recruitment and some other duties.

Girls in festive clothes. Yazovaya village, Bukhtarma district (Bukhtarma “masons”) Photo by E. E. Blomkvist and N. P. Grinkova (1927)

After receiving official status as Russian subjects, masons moved to more convenient places to live. In 1792, instead of 30 small settlements, 9 villages were formed, in which just over 300 people lived: Osochikha (Bogatyrevo), Bykovo, Sennoye, Korobikha, Pechi, Yazovaya, Belaya, Fykalka, Malonarymskaya (Ognevo).

Russian masons. A trip to the arable land with a scythe. D. Korobikha, 1927. Photo by A.N. Beloslyudov. Source: Bukhtarma Old Believers. Materials of the Expeditionary Research Commission

These are brief information about the initial history of Bukhtarma masons who settled in the region as a result of spontaneous free migrations. The formation of Old Believer settlements in the western part of Altai, which occurred at the same time as in the Bukhtarma valley, was of a different nature, as it was a consequence of government orders. In connection with the expansion of the mining industry, the need arose to strengthen the Kolyvan-Voskresensk border line, which involved the construction of new redoubts and outposts. It was necessary to increase the number of miners, and consequently, peasant farmers, to provide workers and military personnel with food.

In 1760, a Senate decree was issued “On occupying places in Siberia from the Ust-Kamenogorsk fortress along the Bukhtarma River and further to Lake Teletskoye, on building fortresses there in convenient places and settling that side along the Ube, Ulba, Berezovka, Glubokaya and other rivers.” rivers flowing into the Irtysh River, Russian people up to two thousand people.” In this regard, the Senate, based on the manifesto of Catherine II of December 4, 1761, invited Russian Old Believers who fled from religious persecution to Poland to return to Russia. At the same time, it was indicated that they could choose either the previous place of residence or one designated at the disposal of the empress, which included Siberia.

Thus, some Old Believers settled here voluntarily, but many, especially the residents of the settlement of Vetki (5), which was part of Poland, were deported to this territory by force. In 1765, a special order was issued, which ordered that fugitives from Poland and Lithuania be exiled to Siberia, so in Altai they began to be called Poles.

In the 1760s all the indigenous villages of the “Poles” were founded in the Zmeinogorsk district: Ekaterininka, Alexandrovskaya volost; Shemonaikha, Losikha (Verkh-Uba), Sekisovka, Vladimir volost; Bobrovka, Bobrovskaya volost. Soon new villages appeared, where the inhabitants were only Old Believers: Malaya Ubinka, Bystrukha, Vladimir volost; Cheremshanka, Butakovo, Ridder volost and some others.

On May 21, 1779, an order was issued to assign Polish peasants to factories, which obligated them to carry out not only agricultural work, but also cutting down forests, exporting finished ore, etc. Until 1861, the Poles were assigned to the Kolyvano-Voskresensky mining plants. Unlike masons, they had to perform all state duties and pay a double poll tax as schismatics.

“Polish” children in everyday home clothes. Photo by A. E. Novoselov

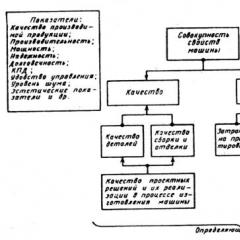

Thus, the history of the Altai Old Believers of the 18th century. is divided into two stages: the first half of the century, when only a few fugitive Old Believers entered the region, and the second half - the time of the formation of settled settlements in this territory (in the 1750s - 1790s - masons, in the 1760s - 1800s. - Poles). XIX century characterized by a general stabilization of the life of the Altai Old Believers. This is evidenced by the active process of formation of new villages (6), the establishment of connections between various Old Believer sects, due to their religious community (7).

In the 19th century representatives of both priestly and non-priestly consents lived in Altai (8). Old Believers-Priests came to Altai in Aleiskaya, Aleksandrovskaya, Bobrovskaya, Vladimirskaya, Ridderskaya volosts after the “forcing out” of the settlements on Vetka. Later, as a result of escapes to the free lands of masons, priests appeared in Bukhtarminsky district. Beglopopov communities were concentrated in Bystrukha, Malaya Ubinka, and Cheremshanka. Since the 1850s the spread of the Belokrinitsky priesthood is noted among the Altai Poles, and since 1908 - among the masons, whose Belokrinitsky church was first located in Bogatyrevo, and since 1917 in Korobikha (9).

Since 1800, the Edinoverie Church began to exist, which is transitional between the Old Believers and the Synodal. It was subordinate to the bishops of the New Believer Church, but services there were performed according to old books in accordance with Old Believer guidelines. In Altai, the most numerous Edinoverie parishes were in Orlovka, Poperechnaya, Ekaterininka of the Alexander volost, Verkh-Uba, Shemonaikha of the Vladimir volost, as well as some villages of masons (Topolnoye, Kamyshenka). In the second half of the 19th century. the Cathedral of Edinoverie functioned in Barnaul (priest Father Mikhail Kandaurov).

The role of intermediate between the priestly and non-priestly agreements is played by the chapel, old man and deacon’s talk (10). The Ural and Siberian chapels actively assimilated with the Altai Beglopopovites in the 1780s. In the valleys of Bukhtarma and Koksa, on the shores of Lake Teletskoye, the old man's talk is most common. In the indigenous settlements of the Poles - the suburbs of Ust-Kamenogorsk, the villages of the Ridder volost - there were Dyakonovsky ones.

One of the most numerous bespopovsky talk in Altai is Pomeranian. Pomeranian communities are spread throughout the region. The Bespopovites-Fedoseevites came to Altai due to the massive resettlement of Vetkovites here. Their indigenous villages were Verkh-Uba, Butakovo, Vydrikha, Bobrovka, Tarkhanka (11). In Butakovo, Cheremshanka, Bystrukha, Malaya Ubinka lived Bespopovtsy tyrants (12). In the Uba valley there lived representatives of such non-popovist sects as the Spasovtsy (13) (Netovtsy), Okhovtsy (14) (non-Molyaks) who came to Altai from the Volga region, in the villages along the Uba and Anuy rivers - Samokresty (15), in Yazovaya and Pechi of the Bukhtarma volost - fellow fans (dyrniks) (16), along the river. Bukhtarma and in the Zmeinogorsk district - runners (17) (wanderers), which increased the diversity of the ritual-dogmatic picture of the Altai Old Believers of the 19th century. At this time, the main spiritual centers of the region stand out. The prayer houses in Kondratyevo, Turgusun, Vydrikha, Sekisovka, Verkh-Uba, Cheremshanka, and Belaya were famous for their decoration and competent conduct of services.

History has preserved the names of the most authoritative Old Believer mentors of the 19th century. Among the priests in 1800 - 1820s. Egor Alekseev (Krutoberezovka), Trofim Sokolov (Malaya Ubinka), Platon Guslyakov (Verkh-Uba) were highly respected; in the 30s - 40s. - Nikita Zelenkov (Turgusun), Ivan Panteleev (Snegirevo), Ekaterina Karelskikh (Bukhtarma villages); in the 50s - 60s. - Ivan Golovanov (Bistrukha); in the 70s - 80s. - Fedor Eremeev (Tarkhanka); among the Bespopovites - Ivan Krivonogov (Vydrikha), Karp Rachenkov (Butakovo), Fyodor Sheshunnikov (Tarkhanka), Guriy Kostin (Bobrovka), Yasson Zyryanov (Belaya).

IN late XIX- early 20th century The number of Old Believer monasteries is growing. The monasteries functioned near Ridder, Verkh-Uba, Ust-Kamenogorsk, Zmeinogorsk, on the river. Bashelak, near the villages of Ponomari and Kordon, Charysh volost, in the area of the volost center of Srednekrasilovo, not far from Zalesovo (in the town of Mikulushkino swamp), in Chulyshman in the Altai Mountains (18). During this period, a fairly large group of Old Believers - immigrants from Russia - came to Altai. At the beginning of the 20th century. Old Believers populate Kulunda. About 15 families of Old Believers arrived in Altai in 1898 from the Voronezh province. They settled in the village. Petukhovo of the present Klyuchevsky district. But since the bulk of the Petukhovites were Nikonians, the Old Believers immigrants wanted to form separate villages. And when in the early 1900s. The government allocated plots of land for settling the Kulundinskaya steppe; the Old Believers turned to the head of the resettlement with a request to give them land, citing religious incompatibility. In 1908, the resettlement of Old Believers to the Kulunda steppe began. Thus, the Kulunda Old Believers belong to the late settlement group of the non-indigenous Siberian population.

In general, the second half of the 19th - beginning of the 20th centuries. - the most favorable period in the history of the Altai Old Believers (19). It was a time of intense spiritual life, including full-fledged ritual and liturgical practice, understanding of the dogmatic issues of the Old Belief; the formation of libraries of spiritual literature and iconostasis in prayer houses, the functioning of Old Believer schools, which taught the Church Slavonic language and hook singing, which contributed to the preservation of liturgical traditions; production of handwritten books by monastery scribes and desert dwellers on the river. Ube (mentor V.G. Tregubov).

With the establishment of Soviet power in the region in the 20s. In the 20th century, religious oppression began: houses of worship were closed, believers were persecuted, religious customs and traditions were desecrated. A lot of spiritual literature was confiscated, iconostases were destroyed. Many communities have lost competent charter leaders. The Old Believers again went “underground”, once again suffering oppression and persecution from the state (20).

And only recently has there been a religious revival, as evidenced by the registration of Old Believer communities throughout the region, the opening of new prayer houses, the attraction of the younger generation to the communities, the resumption of teaching hook singing (in particular, in the parishes of the Russian Orthodox Church (21) of Barnaul, Biysk, Ust-Kamenogorsk ) etc. However, such processes do not appear everywhere. In settlements remote from urban centers, the opposite trends of destruction and extinction of spiritual traditions prevail.

As shown by expeditionary research by employees of the Novosibirsk Conservatory to the areas where Old Believers lived in 1993 - 1997. (22), current state Old Believer settlements in Altai underwent certain changes. In the region there are popovtsy-Belokrinichniki, Beglopopovtsy and representatives of eight non-popovsky denominations: Pomeranians, Fedoseevtsy, Filippovtsy, Chapelnyy, Starikovtsy, Dyakonovtsy, Melchizedeks, Runners (presumably).

The main centers of the Belokrinitsky Old Believers are located in Barnaul (priest Fr. Nikola), Biysk (priest Fr. Mikhail), Ust-Kamenogorsk (priest Fr. Gleb). Thanks to the missionary activities of clergy, there is an active growth of Belokrinitsky communities in the regional centers of Krasnogorskoye, Zalesovo, Blagoveshchenka, Gorno-Altaisk, villages of the Ust-Koksinsky district of the Altai Republic, Glubokovsky and Shemonaikha districts of the East Kazakhstan region. In some settlements (Barnaul, Biysk, Zalesovo, the village of Multa, Ust-Koksinsky district), temples are being built (23).

The Beglopopovskaya community, numbering up to 100 people, which has its own church, has survived in the village. Cheremshanka, Glubokovsky district, East Kazakhstan region. Old Believers-Beglopopovtsy also live in the villages of Kordon and Peshcherka in the Zalesovsky district and in the city of Zarinsk. Some of the Beglopopovites came to Peshcherka from Kamenka, which ceased to exist in 1957 due to the unification of collective farms, where there once was a church. According to the testimony of local residents, until quite recently there was a large community in Zarinsk, but after the death of the mentor, community (cathedral) services stopped and the prayer house was sold. Currently, priest Fr. Andrey from the village. Barite (Ursk) Kemerovo region.

The numerically predominant non-priest sense of Altai remains Pomeranian. Pomeranian communities are concentrated in Barnaul (mentors A.V. Gutov, A.V. Mozoleva), Biysk (mentor F.F. Serebrennikov), Ust-Kamenogorsk (mentor M.K. Farafonova), Leninogorsk (mentors I.K. Gruzinov , A.Ya. Nemtsev), Serebryansk (mentor E.Ya. Neustroev). Places of compact residence of Pomeranians are Aleysky, Altaisky, Biysky, Charyshsky districts Altai Territory, as well as Glubokovsky district of the East Kazakhstan region. In Leninogorsk back in the early 1990s. There was a Pomeranian women's monastery in which there were two nuns and a novice. Most of the Pomeranians are natives of Altai, but there are also migrants from Tomsk region, Tobolsk, from the Urals.

In some villages (Verkh-Uba, Butakovo, Malaya Uba) Pomeranians are called tyrants. Nowadays there is no separate sect of tyrants left in Altai. They joined the Pomeranians and accepted their dogma and rituals. All that remained was the name, which in the original Samodurov villages passed on to the Pomeranians.

Fedoseevites live in the villages of Bobrovka, Tarkhanka, Butakovo, Glubokovsky district, East Kazakhstan region (mentor E.F. Poltoranina). Once upon a time, the Fedoseevites of these places had two prayer houses. Now they gather only on big holidays in Butakovo.

The Filippov Old Believers survived in the Zalesovsky and Zarinsky districts. They came to these places from Vyatka. However, most of them were in the 1930-1940s. migrated to Belovsky and Guryevsky districts of the Kemerovo region.

The Melchizedek Old Believers living in Zalesovo and Biysk also have Vyatka origin (the full name of the sect is the Old Cephalic Church of the Order of Melchizedek). This is the only community of the now rare Old Believers discovered in Siberia. From a conversation with a resident of Zalesovo 3. Kuznetsova, it turned out that their community used to number up to 70 people, the priest was Fr. Timofey, killed during the years of repression; the church building burned down in the 1960s. Now only seven Melchizedeks live in Zalesovo.

Interesting information about the Melchizedeks - closed to communication and low-contact Old Believers - was given by the daughter of the mentor of the Biysk community: “Currently, we no longer have priests, the last of them died in the 60s, so now they are not ordained to the priesthood. My grandfather (the father of the current mentor) was a bishop, lived in Vyatka, moved to Siberia in the 30s, fleeing collectivization: first to the Tomsk region, the village of Kargasok, then to Altai. My father attended a church school as a child and studied the rules there. Apart from him, there are no literate people in the community.”

The informant told us that the Melchizedeks have their own calendar and books, the main one of which is the Book of Hours. They do not use foreign or new books. The service is conducted in Church Slavonic, chants are sung during the speech. Worldly songs are prohibited, only the singing of spiritual verses is permissible. They make their own candles, which are blessed by the mentor. During sacrament hours they receive communion with water and prosphora. Due to the lack of priests, wedding rites are not performed, only blessings for marriage are given. Previously, they blessed only people of their own faith; now marriage of people of different faiths is allowed, but only a member of the community receives the blessing. Children are baptized in the font, adults - in the river. Only men have the right to baptize, bless, receive confession, and lead the charter. Due to the unification of several parishes, three temple holidays are celebrated: the prophet Elijah, the icon of the Vladimir Mother of God, and the Great Martyr George the Victorious.

The Melchizedeks still “keep the cup” very strictly. Previously, after passing travelers, the dishes used by them were thrown away, now there is a separate set of dishes for worldly people. Melchizedeks prefer not to communicate with people of other faiths and not to say anything about their faith.

As before, the most common sense in the south of Altai remains old man's. There are known elderly communities in Gorno-Altaisk (mentor V.I. Filippova), Mayma (mentor N.S. Sukhoplyuev), Zyryanovsk (mentors M.S. Rakhmanov, L.A. Vykhodtsev), the villages of Bogatyrevo, Snegirevo, Parygino (mentor T.I. Loschilov), Putintsevo (mentor T. Shitsyn) Zyryanovsky district, r.p. Ust-Koksa and the villages of Verkhny and Nizhny Uimon, Tikhonkaya, Chendek, Multa (mentor F.E. Ivanov) of the Ust-Koksinsky district, Yailyu of the Turochaksky district.

The old people of Gorny Altai are distinguished by the originality of their ideas, as well as the strictness of their morals (the self-name of the group is old people). Many of them have given up state pensions and are trying to live by subsistence farming, buying necessary products in stores as little as possible. Old people have separate dishes so as not to become defiled by sharing a meal with worldly people. They do not accept the tape recorder, radio, television, telephone, considering them “demonic.”

Altai elders are characterized by ritual features. In particular, when receiving communion, they use not prosphora, but Epiphany water (the village of Multa, Ust-Koksinsky district), and on Easter - an egg that has lain for a year in front of the icons since last Easter (the village of Yailyu, Turochaksky district). When transitioning to the old age, Nikonians must be baptized again, while Belokrinichniks are baptized with “renunciation” (denial of heresy). According to F.O. Bochkareva from the village of Tikhonkaya, “to accept our faith, before being baptized, it is necessary to study the charter for three years. We will find an interpretation of this in the Gospel parable about the owner and the gardener, who took care of a tree for three years, which bloomed only in the fourth year.”

The spiritual leader of the elderly community is the abbot. According to V.I. Filippova from Gorno-Altaisk, “the rector is almost a priest. He has the right to remove people from the cathedral and bring the newlyweds together.” In Multa, the abbot retains the title “priest”; all problems are resolved by the council (i.e., the community) during a spiritual conversation. The most controversial dogmatic issues include the funeral of the deceased without repentance.

The Old People deliberately do not spread their faith.

“You must hide your faith so that outsiders do not ridicule the Scriptures and consider everything that is written there as fairy tales and fables. Our faith will not die from this, it will only become thinner and stretched into a thread,” states F.O. Bochkareva.

It is known that in the mountains on Lake Teletskoye there are monasteries and a convent for the elderly.

Russian peasants. A family of Old Believers from the village. Katanda. 1915 Author N.V. Novikov. From the funds of the Altai State Museum of Local Lore

According to the message of Old Believer A. Isakova from the village. Chendek, Ust-Koksinsky district, the old man’s church used to be in Katanda. She said that the Old Believers of Koksa communicated with the Bukhtarma people, as well as the Kerzhaks of Biysk and Barnaul. Currently, the center of the Koksa old man community is the village of Multa. Old people from Chendek, Upper and Lower Uimon, and Tikhonkaya come here for big holidays. According to the memoirs of M.K. Kazantseva:

“in Multa there was once a large prayer room, consisting of two compartments: the right one for men, the left one for women, with a common lectern. The service lasted from four in the evening until nine in the morning. Rich villagers maintained the house of worship.”

If in villages there is a tendency to unite old people around a single center, then in urban communities the opposite processes are taking place. So, in the recent past, the community in Gorno-Altaisk split into two, the second is now meeting in Mayma. The once large parish in Zyryanovsk, for the convenience of performing divine services, was divided into two groups back in the 1960s, and at present the Zyryanovsk Old Believers are not moving towards rapprochement, having formed separate communities under the spiritual leadership of M.S. Rakhmanov and L.A. Vykhodtsev.

In Biysk, old people are called “dismissed”. As explained by F.F. Serebrennikov, the Biysk old men split off from the chapels, joining the Edinoverie, then they turned away from Edinoverie, considering it Nikonianism, and the chapels are theirs. they were not accepted back, which is why they began to be called unsubscribed, then - old people. There is a similar community in the village. Topolnoye, Soloneshinsky district (mentor A.A. Filippova).

Old Believers, who call themselves chapels, are found in the villages of the Tyumentsevsky district.

Dyakonovshchina (self-name Dyakovsky) has been preserved in Rudny Altai in the suburbs of Ust-Kamenogorsk and the village. Cheremshanka, Glubokovsky district, East Kazakhstan region (mentor T.S. Denisova) - only about 50 people.

“Ipekhashniks” live in Rubtsovsk, Zmeinogorsk, and villages of Zmeinogorsk and Tretyakov districts. Apparently, these are the descendants of the once numerous running class of true Orthodox Christians in Altai.

From the memories of residents of Zmeinogorsk:

“During the war years, a holy old man, a seer, lived in these parts and performed healings in front of people. His name was Demetrius, he was a simple Christian until he heard a voice from heaven. Since believers were persecuted, he hid in secret corners and alleys, where people came to pray. Then Dimitri was found and tried, and since then he has been missing. His work was continued by his son Mikhail, who returned from the war. However, he was also tried for giving up his passport. Mikhail returned from prison crippled, but continued his religious activities. About 40 people joined him.”

Now there are no more than 10 such people left. They do not accept the priesthood, calling modern priests “cult workers” who “do not serve, but work.” The sacrament of communion is performed independently: after fasting, they take holy baptismal water, bring repentance before the Gospel - thereby communing with the Holy Spirit (“in the Spirit is the truth”). Many military personnel refused pensions, believing that money is given not by God, but by the devil, from passports, as the seal of the Antichrist who has reigned in the world; The electricity has been turned off, candles are used, and food is cooked over a fire in the oven. These people try to live in isolation, having as little contact with the “world” as possible.

It should be noted that in some Bukhtarma villages (Bykovo, Bogatyrevo, Zyryanovsky district, Soldatovo, Bolshenarymsky district) local residents distinguish the Polish Old Believers. Apparently, these are the descendants of Poles who moved to live in Kamen, but at the same time retained their distinctive features in everyday life and church practice. The Polyakovsky Old Believers formed a unique independent interpretation of local significance. Resident of the village Bogatyrevo U.O. Biryukova reported that the Polyakovskys fled from Soviet power to China and then returned to Bukhtarma in the 1950s and 1960s. Previously, they had their own prayer house, which differed from the old man’s in the absence of bells. In worship they have more singing, and their chants are more chanting and extended.

Old Believers of the village of Bykova (village of Bykovo) of Bukhtarma district (Bukhtarma “masons”). Photo by A. N. Beloslyudov (1912-1914)

There was information that Zalesovo was home to representatives of such a rare and small group as neo-okruzhniki. However, expeditionary research showed that there is no neo-Okruzhnikov community here. There are some Old Believers who consider themselves both neo-circulators and Melchizedeks. It is likely that the existence of the word “neo-okruzhniki” indicates the existence of this sense in Altai in the past, which was then assimilated with other Old Believer agreements.

In general, different trends prevail among modern Old Believers-priests and non-priests. In priestly communities there is an intensification of spiritual life, a desire not only to preserve their traditions, but also to continue them in new conditions. The priests are not characterized by religious isolation. Contacts have been established between their communities both within the region and beyond: with fellow believers in Novosibirsk, Moscow, Odessa, and Belarus. Among the Bespopovites, there is no unity of views on ritual-dogmatic and customary-legal aspects, which largely contributes to the destruction and extinction of spiritual traditions, up to the disappearance of some interpretations, their merging with the initially dominant one (24).

So, the more than 250-year history of the Altai Old Believers continues to develop, enriched with new events and facts. The uniqueness of this region is largely due to the multi-layered Old Believer culture. Along with the old-time layer of Altai Old Believers, there is a group of later settlers. A large number of interpretations and agreements on the territory of Altai introduces additional fragmentation and indicates the heterogeneity of the phenomenon being studied. Constant migration processes associated with the outflow of population due to political events (25), discoveries and development of ore deposits, large construction projects, for example, such as the Bukhtarma hydroelectric power station, give a dynamic character to the map of Old Believer settlements.

There is no doubt that Altai is one of the most interesting and promising regions for the study of the Old Believers, therefore the systematic collection of material in order to study the current state of the Altai Old Believers must be continued in the future, which will complement and expand our understanding of this unique historical and cultural phenomenon.

Notes

(1) Thus, the foundation of the Biysk fortress dates back to 1709, the Kolyvan-Chaussky fort - to 1713. In the same year, Prince M.P. Gagarin informed Peter I about the possibility of building fortresses along the Irtysh to strengthen the line through Dzungaria. In 1718 the Semipalatinsk fortress was founded, in 1720 - the Ust-Kamenogorsk fortress. In 1723, the first ore deposit was discovered on the river. Loktevka, where in 1726 A.N. Demidov founded the Kolyvan copper smelter. The subsequent discoveries of ore deposits contributed to the opening of mining plants: Barnaul, Shulbinsky, Zmeinogorsky, in the second half of the 18th century. - Pavlovsky, Loktevsky, Zyryanovsky, Gavrilovsky.

(2) These decrees were supported by others. In particular, in 1735 (according to other sources, in 1738) a census of schismatics at the Demidov factories was scheduled to include them in the feudal tax system.

(3) K.V. Chistov identified seven copies and three editions of the Belovodsk legend.

(4) Let us present a version of the legend recorded by the author of the article during the 1993 expedition to the village. Parygino, Zyryanovsky district, East Kazakhstan region from A. Loschilova, born in 1926: “People gathered, dried crackers, and went to Belovodye. They drive, drag the sled, and leave nicks. So we got to the big ice mountain. They began to climb on it, and the traces immediately behind them froze and disappeared. Finally, the sled rolled downhill, and there was the sea or a big river. No matter where they rush, everything is deep. Only one was able to cross the water, because he was from there (Belovodsk). Either they have a bridge under water, or there are some secret signs, or maybe what prayers they know, in general, not everyone, but only a select few can get to Belovodye.”

(5) Polish Branch is one of the spiritual centers of the Old Believers, along with Kerzhenets, Starodubye, Irgiz, Rogozhsky and Preobrazhensky villages in Moscow. The first Old Believer settlements were founded on Vetka by fugitives from Starodubye. Soon about 20 settlements were formed, where people from other parts of Russia settled. The entire territory inhabited by Old Believers began to be called Vetka. Monasteries and monasteries were founded here, in which priests were trained for individual parishes, polemical works were written in defense of the Old Believers, etc.

The tsarist government tried several times to “ruin” Vetka: books and icons were confiscated from monasteries and houses, all buildings were burned, and the population was resettled. The first defeat of Vetka, known as “vygonki,” occurred in 1735, but soon the Old Believers settled there again. In the early 60s. XVIII century the second “forcing” of Vetka took place.

(6) In the territory where Poles live - Volchikha, Zimovye, Poperechnoye, Pikhtovka, Strezhnaya, Orlovka, Tarhanka, Chistopolka, Aleksandrovka; masons - Berel, Kamenka, Berezovka, Turgusun, Snegirevo, Krestovka, Solovyevo, Parygino. Settlements of the Uimon Old Believers are founded - Upper and Lower Uimon.

(7) The Poles fled to Kamen from the unbearable burden of mining duties. Masons, among whom the male population predominated, often took wives from Polish villages. The commonality of these population groups is clearly expressed in the wedding ceremony.

(8) The division of the Old Believers into two agreements occurred in the 90s. XVII century after the death of all the priests of the old ordination. One part of the Old Believers - the priests - accepted fugitive priests from the New Believer church. The other - the priestless people - did not recognize the priests of the new installation and thereby lost such church sacraments as the Eucharist, confirmation, consecration of oil, and marriage. To perform church services, as well as the sacraments of baptism, repentance, and, in some cases, marriage, Bespopovites select spiritual mentors from members of the community.

(9) The Belokrinitsky (Austrian) consent received its name due to a significant event in the history of the Old Believers that took place in 1846 in Belaya Krinitsa, Austria. This year, the three-rank hierarchy was restored in the Old Believer Church due to the accession of Metropolitan Ambrose of Bosno-Sarajevo to the Old Believers. Thus, the Old Believer Church acquired its own bishop, endowed with the right to ordain.

However, not all Old Believers-priests accepted the Belokrinitsky hierarchy. Some continued to perform divine services and church sacraments with the help of fugitive, disrobed priests of the New Believers Church. They received the name Beglopopovtsy. Beglopopism, in fact, was the first form of clericalism, but it took shape in its own right after the establishment of the Belokrinitsky hierarchy, in contrast to it.

(10) They arose in the Kerzhen monasteries and in the initial period they represented branches of the Beglopopovism. Over time, the communities of these denominations began to elect spiritual fathers who were endowed with the right to perform a number of church sacraments. This is how these rumors degenerated into priestless ones.

Chapel consent (old manism is one of its self-names) is so called due to the performance of services in chapels devoid of altars. An important distinguishing principle of their dogma is the refusal to cross other consents among Old Believers who have converted to oldism. The chapels themselves trace their origins to the Kerzhen monk Sophrony.

Dyakonovskoe consent was founded at the beginning of the 18th century. Old Believer writer and polemicist T.M. Lysenin. Its name is associated with one of the most active figures - Hierodeacon Alexander (executed in 1720). The Dyakonovites allowed Old Believers to perform civic duties, serve in the army, and communicate with Nikonians. Unlike the Beglopopovites, they recognize the four-pointed cross on an equal basis with the eight-pointed one.

(11) In the first years of its existence, non-priesthood was represented by the Pomeranian sense, founded in the 1690s. in the Olonets province by brothers Andrei and Semyon Denisov and clerk Danila Vikulin. Councils of 1692 and 1694 decided that mentors could not perform the sacraments assigned to priests, and therefore the inadmissibility of marriage was proclaimed. However, soon some of the Pomeranians, on the initiative of the Moscow mentor Vasily Emelyanov, abandoned celibacy. Subsequently, they recognized the double tax established by Peter 1, began to pray for the king, and eschatological motives in their sermons somewhat weakened.

The Old Believers, who remained in their previous positions, separated into an independent group under the leadership of Fedosei Vasiliev. Fedoseevism arose in Poland. Over time, the asceticism of the Fedoseevites softened: married members of the community were subject to penance, and in old age they were allowed to fully participate in church life. The Fedoseevites are sometimes called celibates, and the Pomeranians are classified as consensual, since the latter do not recognize the sinfulness of marriage.

(12) The Samodurovites did not recognize any other sacraments except baptism. At the same time, baptism only in infancy was considered invalid, since it was not realized by the person. In this regard, their basic dogma justifies the need for secondary baptism. In addition, the tyrants did not pray to icons, but had only a Crucifix in each room without an image of the Holy Spirit.

(13) Spasovites (founder - Kozma Andreev, the sense arose in the Kerzhen monasteries at the turn of the 17th-18th centuries) believe that it is necessary to pray to the Savior without witnesses and intermediaries, since they reject traditional Orthodox dogmas and rituals, replacing them with “skete repentance” . As V. Anderson notes, they make confession in private, before the image of the Savior or the Mother of God, since they do not recognize other icons. A significant difference between Spasovites and other Bespopovites is that they do not rebaptize other Orthodox Christians, because they are convinced that a person must be baptized once. Another name for consent - netovshchina - is associated with the denial of the sacraments, priesthood, temples, and monasteries.

(14) The Okhovtsy come into separate agreement with non-Tovism. Realizing the sinfulness of life, they prefer to sigh about their sins instead of praying. This is where their other names came from - nemolyaks and sighers. Believing in the impossibility of salvation, they abandoned not only prayers, but also icons. True prayer is “not in the stretching of hands and standing in front of the body and seen with the tongue of the beholder, but in mental teaching.”

(15) The name of the self-crosses comes from the personal performance of the sacrament of baptism by the believers themselves without an intermediary: “they will undress and immerse themselves in Uba with prayer, put on clean linen and call themselves a new name according to the calendar,” testifies G.D. Grebenshchikov.

(16) From the self-crosses originate the Hollers (or fellow worshippers), who do not recognize any objective deity other than God outside of time and space. They pray to God open air, bowing to the east. They have special holes in their houses that they open when they turn to God.

(17) The agreement of wanderers arose in the second half of the 18th century. in the Yaroslavl province (according to most researchers, its founder was the fugitive soldier Euthymius), standing out from Filippovism. Wanderers believe that eternal wandering is necessary to save the soul. Since the Antichrist has reigned in the world, one cannot obey the authorities, perform public duties, or pay taxes. Runners do not recognize passports, renounce their first and last names in order to break ties with civil society, and perceive self-baptism as a religious dogma, so that no one associated with the world of the Antichrist will participate in baptism.

(18) Journalist A. Kratenko tried to restore the history of one of the Old Believer monasteries in Altai. From documentary sources, he found out that in 1899, at the confluence of the river. Bannaya in Ubu was founded by eight sisters who came from the Ufa province. In 1911 there were already about 40 nuns in the monastery. In the 1930s the monastery was destroyed, some of the nuns were imprisoned, after liberation many of them settled in Guslyakovka and Ermolaevka.

(19) Let us note the positive consequences of the decree of April 17, 1905 on religious tolerance: the government’s loyal attitude towards the Old Believers, the end of the moral and economic oppression of the Old Believers.

(20) Let us illustrate the above with the story of A.F. Belogrudova, who comes from the famous Old Believer Dolgov family in Altai, and for a long time was a charter member of the Biysk Belokrinitsa community: “In Soviet times, they prayed secretly; there was no permanent prayer room. For fear of being noticed, worship was performed moving from house to house. Sometimes we had to change places during one service.” The description of such a situation had to be recorded several times, it was so typical for that time.

(21) ROSC - Russian Orthodox Old Believers Church- the official name of the Belokrinitsky (Austrian) consent.

(22) In 1993, expeditions to Rudny Altai (East Kazakhstan region) took place by N.S. Murashova and V.V. Murashov and to Barnaul - I.V. Polozova and L.R. Fattakhova.

In 1996, with the support of the Russian Humanitarian Fund (project 96-04-18023) T.G. Kazantseva, N.S. Murashova, V.V. Murashov and O.A. Svetlov examined Biysk, Gorno-Altaisk, villages of Biysk, Altai, Ust-Koksinsky and Turochaksky districts. In 1997, again thanks to the assistance of the Russian Humanitarian Foundation (project 97-04-18013), six expeditions were carried out: T.G. Kazantsev and A.M. Shamne worked in the Old Believer communities of Barnaul and Biysk; T.G. Kazantseva, N.S. Murashova and V.V. The Murashovs visited the Biysk Pomeranian community during the Easter celebrations, and then in the Zalesovsky and Zarinsky districts; N.S. Murashova and V.V. Murashov was examined by Rubtsovsk, Zmeinogorsk, villages of Zmeinogorsk, Tretyakov and Kurinsky districts; O.A. Svetlova and O.V. Svetlov worked in the Biysk, Altai, Krasnogorsk and Soloneshensk regions; O.A. Svetlova and I.D. Pozdnyakov made a trip to Aleysky, Ust-Kalmansky, Charyshsky districts. The materials of the expeditions are in the Archive of Traditional Music of the Novosibirsk Conservatory.

(23) On September 28, 1997, the consecration of the temple took place (laying the foundation stone of the temple - editor's note) in Biysk. Let's give short description those events according to the expedition diary of T.G. Kazantseva: “The consecration ceremony took place in the courtyard of the house of worship. The foundation, plinth and first crown of logs have been laid at the future temple. The church is small: 10 by 10 m. An iconostasis of three icons was prepared in the courtyard, in the center - the temple icon of the Kazan Mother of God; lamp; table with the Gospel for priests; stand for singing books; in the distance there is a wooden eight-pointed cross. Closer to the house there were tables for a festive meal. The consecration was attended by Biysk priest Fr. Mikhail, Barnaul priest Fr. Nikola, Mother Marina, who read the canon, sticharion reader Vasily, singers of the Biysk and Barnaul communities (headmaster Alexander Emelyanov). About 100 people were present. The ritual consisted of reading and singing the canon and reading the Gospel. The consecration itself consisted of censing the temple crosswise on four sides and making notches in each corner with an ax, also crosswise. After the prayer service and the consecration of the temple, everyone who took part in the ritual approached the priests in pairs to be sprinkled with holy water. Then a crowded dinner took place with festive speeches and the singing of spiritual poems.

(24) So, among the Pomeranians, on the crucifix a two-hypostatic Deity is depicted (there is no dove - a symbol of the Holy Spirit). During baptism, Pomeranians do not walk around the font: both the spiritual father and the godson face the east. Among the old people, the spiritual father approaches the font from the west, and then turns to the east. Different opinions among Old Believers call for the need to “observe the cup,” communicate with the “world,” use money, apply to government agencies, etc.

Currently, there are no differences between Pomeranians and Fedoseevites. The Samodurovites lost their independent status, dissolving among the Pomeranians. In the ideology of the Pomeranians, there is a penetration of spiritual motives of wandering, in particular negative attitude to passports and other documents as to the seal of the devil.

(25) For example, in the 1920-1930s. many Old Believers left Soviet power for China in the 1950s and 1960s. some of them returned to their homeland after a 30-year stay with Old Believers from other regions.

Op.: Traditions of spiritual singing in the culture of Old Believers of Altai. Novosibirsk: Nauka, 2002.

The Russian emigrants discussed below are not at all the same emigrants who flooded Europe and the USA in the nineties and 2000s. These Russians, or rather not even them, but their ancestors, moved here even before the October Revolution, and some even after the Great Patriotic War. It is interesting to see how, being isolated, they managed to preserve their culture and their language. Moreover, most of them are Old Believers - adherents of that Orthodox Church that was before Peter I.

But in Brazil this matter turned out to be difficult. Finding out where these colonies are located turned out to be extremely difficult. An active search on the Internet showed that there are three main such colonies - in Mato Grosso, Amazonia and Paraná. The first two were located extremely far from our route, and about the one on the border of the states of Parana and Sao Paulo, there was practically no information on the Internet. The Russian couple with whom we were staying in Curitiba told us about their approximate location. But we still decided to try our luck in other countries, in particular in Uruguay. It turned out that doing this here is much easier.

In the Estonian outback, Old Believers cherish the Russian language and traditions

Modern followers of the Old Believers are already accustomed to celebrating the holiday with everyone on the night of January 1, but faith still does not allow them to expect gifts from the pagan - Frost. MK in St. Petersburg learned about how tradition and modernity coexist in the community of the Peipus Old Believers when visiting these “our people in Estonia.”

No magic under the tree

For Old Believers, of course, Christmas is more important than the New Year. It is celebrated, as in Russia, on the night of January 7th. But also New Year has long taken root in Old Believer communities. True, the Nativity fast is observed there much more strictly, and therefore on December 31 the table is not bursting with food.

Country of prohibitions

A place where there is not a single photo on the Internet. A village where men - red-haired, blue-eyed, bearded men - are eligible grooms for brides from Brazil and the USA. There is no cell phone reception here, there is not a single satellite dish, and communication with the world is only a single payphone. Eastern Siberia. Turukhansky region. Old Believer village of Sandakches. The magazine “Father, you are a transformer” is the first publication to whose author local residents trusted their secrets.

In the wild: The story of a family who lived for 40 years in the taiga without contact with the outside world

We have written about this hermit more than once. Last visit . Today is another fresh article about how the family of Agafya Lykova, the last of the family of hermits to survive to this day, survived.

While humanity was experiencing the Second world war and launched the first space satellites, a family of Russian hermits fought for survival by eating bark and reinventing primitive household tools in the remote taiga, 250 kilometers from the nearest village. Smithsonianmag magazine recalls why they fled from civilization and how they survived the collision with it.

"Agafia" (doc. film)

Agafya Karpovna Lykova (born April 16, 1944, RSFSR) is a famous Siberian hermit from the Lykov family of Old Believers-bespopovtsev, living on the Lykov farmstead in the forest of the Abakan ridge of the Western Sayan (Khakassia). This film about her was shot last year. Excellent quality and beautiful views of nature complement and highlight this fascinating story about one of the most famous women in Russia and its neighboring countries.

Thanks to this wonderful documentary from Russia Today, this woman is now known in many other parts of the world. Although the film is for English-speaking viewers, most of the conversation is in Russian with English subtitles. So let's see. And as a bonus, a small article: “HOW A FAMILY SHOULD LIVE ACCORDING TO THE “HOUSE-STRUCTURE” - a collection of advice and teachings from the 16th century.”

Old Believers of Dersu. How does a single family live?

About the Old Believers from the depths of the Ussuri taiga, who moved to Russia from South America, there was already a story. Today, thanks to Alexander Khitrov from Vladivostok, we will visit there again. Specifically, in the Murachev family.

In October we again had the opportunity to visit the Old Believers in Dersu. This time the trip was of a charitable nature. To the Murachev family, who we visited last time, we gave one hundred laying hens and 5 bags of feed for them. The sponsors of this trip were: the Sladva group of companies, the founder of the Shintop chain and the President of the Rus Foundation for Civil Initiatives Dmitry Tsarev, the Ussuriysk Poultry Farm, as well as the parents of the younger group kindergarten"Sailor". From myself personally, from my colleague Vadim Shkodin, who wrote heartfelt texts about the life of the Old Believers, as well as from the family of Ivan and Alexandra Murachev, we express our deep gratitude to everyone for their help and concern!

Domovina

The photo shows the grave of a baby in the Old Believer cemetery in the village. Ust-Tsilma. Old Believers of Pomeranian non-priest consent live there. Of course, Domovins and Golbtsy are echoes of paganism. To combine them with Christianity, they began to embed copper icons or crosses into them. Unfortunately, now, from almost all old cemeteries, they have been stolen... so that the thieves' hands will wither.

Let's find out more about this symbolic structure with a double-sided roof on the graves of Old Believers and a few other facts about burial in Rus'...

Only in Russia will there be a lost paradise. Neither Brazil nor Uruguay are needed.

This story was loud. Six years ago, in Primorye and other Russian regions, under the guarantees of the state program for the voluntary resettlement of compatriots from abroad to Russia, Old Believers from South America - Brazil, Bolivia, Uruguay - began to return to their historical homeland. Unusual in appearance, they have aroused acute ethnographic interest in modern Russian society. Bearded men – blouses with homemade embroidery, sashes. Clear-eyed women - self-made multi-colored sundresses up to their heels, hidden under their headdresses with braids up to the waist... Adherents of the old - pre-Nikonian - ancient Orthodox faith seemed to have stepped out of photographs of ancient times and appeared in Russia in reality, alive and well.

They came with large families with many children (unlike us, many sinners, Old Believers give birth as many as God gives). And we went away from our curiosity - into the wilderness, into abandoned distant villages, where not every jeep can reach. One of these, the village of Dersu, is located deep in the Ussuri taiga in the Krasnoarmeysky district of Primorye.

How do the Old Believers live?

Sergei Dolya writes: The liturgical reform of Patriarch Nikon in the 17th century led to a split in the Church and persecution of dissidents. The bulk of the Old Believers came to Tuva at the end of the 19th century. Then this land belonged to China, which protected the Old Believers from repression. They sought to settle in deserted and inaccessible corners, where no one would oppress them for their faith.

Before leaving their old places, the Old Believers sent scouts. They were sent light, providing only the most necessary: horses, provisions, clothing. Then the settlers set off in large families, usually along the Yenisei in winter, with all the livestock, household scrubs and children. People often died when they fell into ice holes. Those who were lucky enough to arrive alive and healthy carefully chose a place to settle so that they could engage in farming, arable farming, start a vegetable garden, etc.

Old Believers still live in Tuva. For example, Erzhey is the largest Old Believer village in the Kaa-Khem region with a population of more than 200 residents. Read more about it in today's post...

Estonian Piirisaar - the island of hospitable Old Believers

Piirisaar, (from Est. Piirissaar) also known as Zhelachok, is the largest island in the freshwater Lake Peipus and the second largest in the Pskov-Peipsi basin after Kolpina Island. It belongs to the Republic of Estonia and is administratively subordinate to Tartumaa County as part of the Piirissaare parish.

Photo: Mikhail Triboi

Once upon a time he sheltered Old Believers who fled from the reforms, who founded the Russian community. Currently, the indigenous population is 104 people, they speak Russian and are incredibly hospitable. NTV journalists were convinced of this. Watch the report below...

Visiting Agafya Lykova

We have already written more than once about the famous hermit Agafya Karpovna Lykova, who lives on a farm in the upper reaches of the Erinat River in Western Siberia, 300 km from civilization. For example and. Quite recently, civilized people once again visited her and made a short report.

Denis Mukimov writes: The primary purpose of the flight to the Khakassian taiga was a traditional flood control measure - an examination of snow reserves in the upper reaches of the Abakan River. One day we stopped briefly at Agafya Lykova’s...

For 40 years the Russian family lived without communicating with the outside world, without knowing about World War II

Summer in Siberia is short. The snow melts only in May, and the cold returns in September. It turns the taiga into a frozen still life, awe-inspiring with its cold desolation and endless kilometers of thorny pine and soft birch forests, where bears sleep and hungry wolves roam, where mountains stand with steep slopes, where rivers with clear water flow in streams through valleys, where hundreds thousands of frozen swamps. This forest is the last and most majestic in the wild nature of our planet. It extends from the extreme northern regions of the Russian Arctic south to Mongolia, and from the Urals to Pacific Ocean. Five million square miles with a population of only a few thousand people, excluding a few towns.

But when warmer days arrive, the taiga blooms, and for a few short months it can seem almost hospitable. And then a person can look into this hidden world - but not from the ground, for the taiga can swallow entire armies of travelers, but from the air. Siberia is home to much of Russia's oil and minerals, and over the years, even its farthest corners have been traversed by explorers and explorers in search of minerals, only to return to their camps in the wilderness where mining operations take place.